Read the list of statements below.

1. Covid-19 escaped from a Chinese laboratory.

2. Climate change demands a radical transformation of modern lifestyles.

3. Donald Trump colluded with Vladimir Putin to get elected.

4. The real founding of the American project was not in 1776 but in 1619.

5. The FBI investigation into the Trump campaign was based on lies.

6. The Defund the Police movement caused a crime spike in American cities.

7. Kyle Rittenhouse did nothing wrong.

For each statement, write down whether it is true or false, and whether the issue is very important or not that important.

Pick the friend whose political beliefs are most different from yours, and to whom you are still willing to speak. Ask your friend to complete the questionnaire too. Explain to this friend why his or her answers are insane.

On the recent twentieth anniversary of 9/11, I reflected on how I would tell my children about that day when they are older. The fact of the attacks, the motivations of the hijackers, how the United States responded, what it felt like: all of these seemed explicable. What I realized I had no idea how to convey was how important television was to the whole experience.

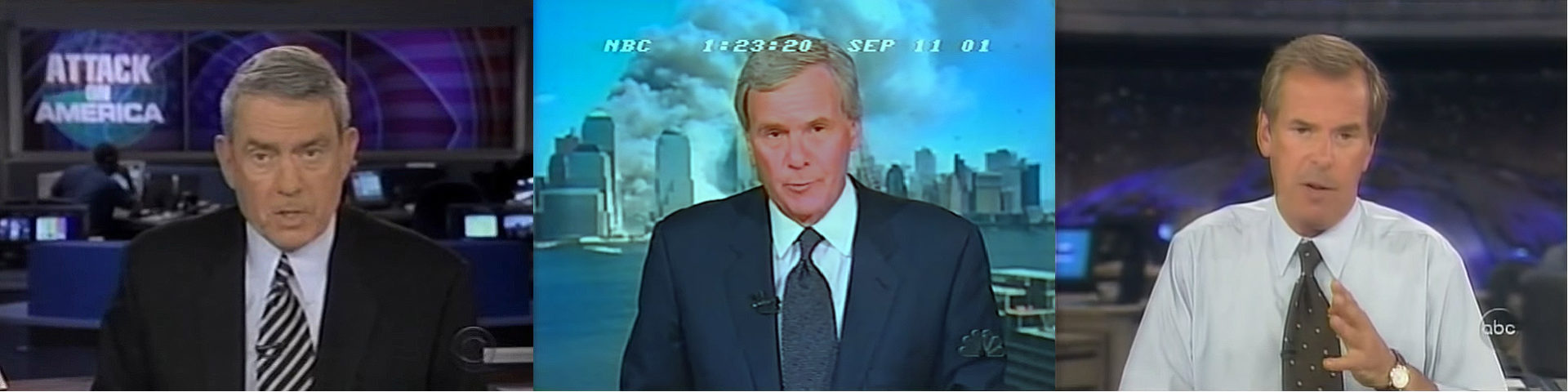

Everyone talks about television when remembering that day. For most Americans, “where you were on 9/11” is mostly the story of how one came to find oneself watching it all unfold on TV. News anchors Dan Rather, Peter Jennings, and Tom Brokaw, broadcasting without ad breaks, held the nation in their thrall for days, probably for the last time. It is not uncommon for survivors of the attacks to mention in interviews or recollections that they did not know what was going on because they did not view it on TV.

If you ask Americans when was the last time they recall feeling truly united as a country, people over the age of thirty will almost certainly point to the aftermath of 9/11. However briefly, everyone was united in grief and anger, and a palpable sense of social solidarity pervaded our communities.

Today, just about the only thing everyone agrees on is how divided we are. On issue after issue of vital public importance, people feel that those on the other side are not merely wrong but crazy — crazy to believe what they do about voter ID, Russiagate, critical race theory, pronouns and gender affirmation, take your pick. Americans have always been divided on important issues, but this level of pulling-your-hair-out, how-can-you-possibly-believe-that division feels like something else.

It is hard to imagine how we would have experienced 9/11 in the era of Facebook and Twitter, but the pandemic provides a suggestive example. Just as in 2001, in 2020 we faced a powerful external threat and had a government willing to meet it. But instead of unity, American society has experienced tremendous fragmentation throughout the pandemic. Beginning with whether banning foreign travel or using the label “Wuhan virus” was racist, to later mask mandates, school closures, lockdowns, and vaccine requirements, we googled, shared, liked, and blocked our way apart. Nobody was tuning in to the same broadcast anymore.

Of course, we have heard no end of laments for the loss of the TV era’s unity. We hear that online life has fragmented our “information ecosystem,” that this breakup has been accelerated by social division, and vice versa. We hear that alienation drives young men to become radicalized on Gab and 4chan. We hear that people who feel that society has left them behind find consolation in QAnon or in anti-vax Facebook groups. We hear about the alone-togetherness of this all.

What we haven’t figured out how to make sense of yet is the fun that many Americans act like they’re having with the national fracture.

Take a moment to reflect on the feeling you get when you see a headline, factoid, or meme that is so perfect, that so neatly addresses some burning controversy or narrative, that you feel compelled to share it. If it seems too good to be true, maybe you’ll pull up Snopes and check it first. But you probably won’t. And even if you do, how much will it really help? Everyone else will spread it anyway. Whether you retweet it or just email it to a friend, the end effect on your network of like-minded contacts — on who believes what — will be the same.

“Confirmation bias” names the idea that people are more likely to believe things that confirm what they already believe. But it does not explain the emotional relish we feel, the sheer delight when something in line with our deepest feelings about the state of the world, something so perfect, comes before us. Those feelings have a lot in common with how we feel when our sports team scores a point or when a dice roll goes our way in a board game.

The unity we felt watching the news unfold on TV gave way to the division we feel watching events unfold online. We all know that social media has played a part in this. But we should not overestimate its impact, because the story is much bigger. It is a story about the shifting foundations of reality itself — a story in which you and I are playing along.

Hello again. I hope you and your friend are still on speaking terms after our fun collaborative activity. Now let’s try something completely different. Follow me, if you will, into dreamland.

Last week, I saw an ad for a movie in the newspaper, with an old clock in the background. But something was funny about it. The numbers were off — 2, 0, 2, 7….

Could this be a phone number? I tried dialing the first ten numbers, and got an automated message of a woman’s voice in a nebulous accent reading another series of numbers. I have been pulling at the thread ever since.

I did some digging and found out that I’ve stumbled on a kind of game: an alternate reality game. I’m guessing you may not have heard of them?

Alternate reality games are a lot like reading Agatha Christie or Sue Grafton or watching Sherlock. There is something deeply satisfying about unraveling a mystery story when we’re taken in by it. No one has really been murdered, but we still feel suspense until the puzzle is solved.

A good mystery writer will hide the clues in plain sight. She doesn’t have to do that. She could just describe how the detective solves the case. But she does it because she knows that we want to see if we can figure it out ourselves!

Now what if you could do more than just follow along with the story? What if you could actually be the detective? Say you notice a clue and you figure out what it means, and it tells you to look for a hidden message in a classified ad in tomorrow’s newspaper. The message tells you to go to a local bakery tomorrow at noon to find another clue.

That’s what happens in an alternate reality game. It’s a story that you play along with in the real world. It’s like an elaborate scavenger hunt, on the Internet and in real life, with millions of other people all over the world playing along too.

Speaking of which, I have a hunch what the numbers from the lady on the phone mean, but I can’t say anything else on an open channel. If you want to help us solve the puzzle, our Signal chat link is ⬛⬛⬛⬛⬛.

During the Trump era, as a wider swath of people began to pay attention to the online right, a group of game designers noticed disturbing parallels between QAnon, with its endlessly complex conspiracy theories, and their own game creations. Most notably, in the summer of 2020, Adrian Hon, designer of the game Perplex City, wrote a widely shared Twitter thread and blog post drawing parallels between QAnon and alternate reality games.

Theory: QAnon is popular partly because the act of “researching” it through obscure forums and videos and blog posts, though more time-consuming than watching TV, is actually *more enjoyable* because it’s an active process.

— Adrian Hon (@adrianhon) July 9, 2020

Game-like, even; or ARG-like, certainly.

An alternate reality game begins when people notice “rabbit holes” — little details they happen across in the course of everyday life that don’t make sense, that seem like clues. Consider the game Why So Serious?, which was actually a marketing campaign for the 2008 Batman movie The Dark Knight. The game started when some fans at a comic book convention found dollar bills with the words “why so serious?,” and George Washington defaced to look like the Joker. Googling the phrase led to a website … which directed players to show up at a certain spot at a certain time … where a skywriting plane appeared and wrote out a phone number … which led to more clues. Eventually you found out that there was a war going on between the Joker’s criminal gang and the Gotham Police.

The “game masters” don’t necessarily write out the whole story in advance. They might make up some parts of it as they go, creating clues in response to what players are doing. Some games offer prizes, like coordinates to a secret party. But really, the reward is just the satisfaction of solving the mystery.

The structural similarities between all this and QAnon, the game designers thought, were remarkable. In QAnon, too, the rabbit holes can be anywhere: YouTube videos, believers carrying signs at Trump rallies with phrases only other followers would recognize, or enigmatic posts on online message boards. QAnon, of course, also has a game master: Q, the unidentified person behind the curtain. Although he or she has lately been silent, Q used to send regular messages, which pointed to leaked emails, obscure news stories, and numerological puzzles.

Like in QAnon, this blending of online and offline is typical for ARGs. Players navigate a thicket of websites, email accounts, even real phone numbers or voicemail accounts whose passwords you have to figure out. The game masters might send you an email from a character, leak a (fake) classified document on an obscure website, or send you to a real-world dead drop to find a USB drive. At one point in the Batman game, players were directed to a specific bakery, where they could give a name from the game and pick up a real cake with a real phone buried inside.

With both QAnon and alternate reality games, it can be hard to tell what is and isn’t “real.” Of course, QAnon followers think that their world is the real world, whereas ARG players know they are in a game. That’s an important difference. But the point of an alternate reality game is also to blur the boundaries of the game. In fact, many use a “this is not a game” conceit, intentionally obscuring what is real and what are made-up parts of the game in order to create a fully immersive experience.

Unlike role-playing games, in an alternate reality game you play as yourself. Part of what’s so much fun is the community that forms among players, mostly online. For devoted players, status accrues to finding clues and providing compelling interpretations, while others can casually follow along with the story as the community reveals it. It is this collaboration — a kind of social sense-making — that builds the alternate reality in the minds of players.

Likewise, once you get interested in QAnon, there is a rich community built through video channels, discussion forums, and Facebook groups. Late-night chats and brainstorming sessions create an atmosphere of camaraderie. Followers make videos and posts that provide compelling interpretations of clues, aggregate the best ideas from the message boards, and simply entertain others playing in the same sandbox. Successful content creators gain social status and make money from their work.

Most of all, QAnon followers find deep personal satisfaction, achievement, and meaning in the work they are doing to trace the strings to the world’s puppeteers. As the journalist Anne Helen Peterson wrote on Twitter: “Was interviewing a QAnon guy the other day who told me just how deeply pleasurable it is for him to analyze/write his ‘stories’ after his kids go to sleep.” That thrill is not unlike what you feel when you play an alternate reality game.

Maybe this idea that QAnon is like an alternate reality game was just a wild theory too. ARG designers and players may be prone to overestimate the importance of parallels, seeing clues where there are none. Or maybe it was prophetic, considering the role that QAnon adherents would play in the U.S. Capitol attack just a few months after this idea garnered widespread attention. Indeed, there is a case — and I am going to make it here — that the parallel can be fruitfully extended much farther.

Adrian Hon points in the right direction:

I don’t mean to say QAnon is an ARG or its creators even know what ARGs are. This is more about convergent evolution, a consequence of what the internet is and allows.

In other words, the similarities between QAnon and alternate reality games do not owe to something uniquely insane about Q followers. Rather, Hon says, both are outgrowths of the same structural features of online life.

Hon writes that in alternate reality games, “if speculation is repeated enough times, if it’s finessed enough, it can harden into accepted fact.” And Michael Andersen, a writer who has dissected ARGs since the aughts, describes the appeal of seeing the finished game this way: “All of the assumptions and logical leaps have been wrapped up and packaged for you, tied up with a nice little bow. Everything makes sense, and you can see how it all flows together.”

Does this sound familiar? If you had encountered out of context the paragraph you just read, what would you think it was about? Widely held beliefs on Russiagate, perhaps? On the origins of the coronavirus? The 2020 election results? Covid hysteria?

Okay, time for another quiz. Read the list of statements below:

1. New facial recognition systems, which are designed by profit-maximizing Silicon Valley companies and could be used by police departments, falsely identify black women 100 times more often than white men.

2. San Francisco has become a paradise for lawlessness, as district attorneys have stopped prosecuting shoplifters, and videos show thieves brazenly walking out of stores with bags full of goods while security guards make no effort to stop them.

3. Under a new biosecurity regime in Europe, thousands of people have been implanted with microchips in their arms that store their Covid vaccination status and ID, allowing them to scan their bodies to access areas available only to those who comply with vaccine requirements.

4. Dark money from ultra-wealthy conservative donors bent on radicalizing the American right has funded a single writer, whose reports have been viewed 250 million times online, to create a MAGA panic over “critical race theory” being taught in schools.

Each of these statements is based on information that has been reported as true by credible mainstream outlets (MIT Media Lab, NBC News, Newsweek, The New Yorker).

Which statement feels most telling — like it speaks to a much bigger story that demands further investigation? Pick one and do the research.

In October 1796, a report appeared in Sylph magazine that sounds peculiar to us today:

Women, of every age, of every condition, contract and retain a taste for novels…. The depravity is universal…. I have actually seen mothers, in miserable garrets, crying for the imaginary distress of an heroine, while their children were crying for bread: and the mistress of a family losing hours over a novel in the parlour, while her maids, in emulation of the example, were similarly employed in the kitchen…. with a dishclout in one hand, and a novel in the other, sobbing o’er the sorrows of Julia, or a Jemima.

Though this may seem silly now, there is reason to think that the eighteenth-century British moralists who panicked over the spread of a new medium were not entirely wrong. Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe, Voltaire’s Candide, Rousseau’s Emile, and Goethe’s The Sorrows of Young Werther, exemplars of the new modern literary form known as the novel, were more than just great works of art — they were new ways of experiencing reality. As literary critic William Deresiewicz has written, novels helped to forge the modern consciousness. They are “exceptionally good at representing subjectivity, at making us feel what it’s like to inhabit a character’s mind.”

Perhaps even revolution was the result. Russian revolutionary activity, in particular, was inextricably tied up with novels. Lenin wrote about Nikolay Chernyshevsky’s novel What Is to Be Done? that “before I came to know the works of Marx … only Chernyshevsky wielded a dominating influence over me, and it all began with What Is to Be Done?,” and that “under its influence hundreds of people became revolutionaries.” He later borrowed the novel’s title for his own 1902 revolutionary tract.

In our day, the departure from consensus reality began in innocent fashion, and with a different genre of entertainment: with wizards and dice rolls in 1970s basements. Board games, war games, and fantasy novels had all been around for a long time. What role-playing games like Dungeons & Dragons pioneered was using the same gameplay mechanics not to fight tabletop wars but to tell stories, centered not on armies but on individual characters of a player’s own creation. The point of playing was not to beat your opponent but to share in the thrill of making up worlds and pretending to act in them. You might be an elven warlock rescuing a maiden, or a dwarven paladin breaking out of a city besieged by orcs. Or you might be the “dungeon master,” the chief storyteller who decides, say, whether the other players encounter a dragon or a manticore.

The role-playing game is to our century what the novel was to the eighteenth: the social art form epitomizing and evangelizing a new mode of self-creation. Role-playing games became especially popular in the 1980s, fostering a moral panic over the corruption of the youth, and their influence has continued to vastly exceed that of table-top games.

As soon as the scientists, students, and computer hobbyists who loved Dungeons & Dragons began connecting with each other through what would come to be called the Internet, they began to play games together. On top of the early text-based online world, they created chat protocols for role-playing games. It was an early form of what Sherry Turkle called “social virtual reality.”

Many of the systems we now use online have their structural origins in the world of role-playing games. Video games of all sorts borrow concepts from them. “Gamified” apps for fitness, language learning, finance, and much else award users with points, badges, and levels. Facebook feeds sort content based on “likes” awarded by users. We build online identities with the same diligence and style with which Dungeons & Dragons players build their characters, checking boxes and filling in attribute fields. A Tinder profile that reads “White nonbinary (they/her) polyamorous thirtysomething dog mom. Web-developer, cross-fit maniac, love Game of Thrones” sounds more like the description of a role-playing character than how anyone would actually describe herself in real life.

Role-playing games combined character-building, world-building, game masters telling stories, creating puzzles, and rules for scoring points and making decisions — all for having fun with friends in an imagined world for a little while. Could we have imported online all of these tools for building alternate realities without getting sucked into the game?

Several weeks have gone by since you picked your rabbit hole. You have done the research, found a newsletter dedicated to unraveling the story, subscribed to a terrific outlet or podcast, and have learned to recognize widespread falsehoods on the subject. If your uncle happens to mention the subject next Thanksgiving, there is so much you could tell him that he wasn’t aware of.

You check your feed and see that a prominent influencer has posted something that seems revealingly dishonest about your subject of choice. You have, at the tip of your fingers, the hottest and funniest take you have ever taken.

1. What do you do?

a. Post with such fervor that your followers shower you with shares before calling Internet 911 to report an online murder.

b. Draft your post, decide to “check” the “facts,” realize the controversy is more complex than you thought, and lose track of real work while trying to shoehorn your original take into the realm of objectivity.

c. Private-message your take, without checking its veracity, to close friends for the laughs or catharsis.

d. Consign your glorious take to the post trash can.

2. How many seconds did it take you to decide?

3. In however small a way, did your action nudge the world toward or away from a shared reality?

Digital discourse creates a game-like structure in our perception of reality. For everything that happens, every fact we gather, every interpretation of it we provide, we have an ongoing ledger of the “points” we could garner by posting about it online.

Sometimes, something will happen in real life that provides such an outstanding move in the game that it will instantly go viral. Conversely, we tend not to talk about things that are important but do not garner many “points.” So, for instance, there has been far less frothy discourse on Twitter and in the New York Times about the restoration of the multi-billion-dollar state and local tax deduction — conservatives give it only a few points for liberal hypocrisy, and for liberals it’s a dead-end — than about Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez’s “Tax the Rich” dress — lots of points in many different worlds.

Alternate reality games dictate what is and is not important in the unending deluge of information — what gets points and what doesn’t. What falls outside of or challenges the story of a given game is not so much disputed as ignored, and whatever fits neatly within it is highlighted. Wanting to understand the facts in perspective cannot alone explain the level of attention paid to vaccine complications, maskless people on planes, drag queen story hours, or school book bans by neofascist state legislatures (have I made everyone mad?). ARGs are not about establishing the facts within consensus reality. They are about finding the most compelling model of reality for a given group. If your ads, social media feeds, Amazon search results, and Netflix recommendations are targeted to you, on the basis of how you fit within a social group exhibiting similar preferences, why not your model of reality?

Perhaps this helps to explain why fact-checking seems so pitiably unequal to our moment. Yes, unlike a genuine game, QAnon followers assert claims about the real world, and so they could, in theory, be verified and falsified. It isn’t all confirmation bias — surprise is still possible: The Pizzagate believer who in 2016 brought a rifle to a D.C. pizza place to rescue child sex slaves from a ring believed to involve Hillary Clinton was genuinely shocked that the building didn’t have a basement. But ARGs can keep going because there are a myriad of possible solutions to puzzles in the game world. Debunking only ever eliminates one small set of narratives, while keeping the master narrative, or the idea of it, intact. For QAnon, or contemporary witchcraft, or #TheResistance, or Infowars, or the idea that all elements of American life are structured by white supremacy, one deleted narrative barely puts a dent in what people are drawn to: the underlying world picture, the big story.

Months have gone by since you went down the rabbit hole.

You are now an expert. You have alienated a few old friends … but made some great new ones, who get you better anyway.

Now consider the following statement:

The more I learn, the more astonished I am that everybody else isn’t taking this story as seriously as I am. My eyes keep opening while other people are going blind.

1. Do you agree or disagree?

2. How do you think the players who picked the other rabbit holes would answer?

To play an alternate reality game is to be drawn into a collaborative project of explaining the world. It is to lose, even fleetingly, one’s commitment to what is most true in the service of what is most compelling, what most advances a narrative one deeply believes. It allows players to neatly slot vast reams of information into intelligible characters and plots, like “Everything that has gone wrong is the product of evil actors or systems, but there are powerful heroes coming to the rescue, and they need your help.” Unlike a board game, this kind of world-building has no natural boundary. Players can become entranced and awe-struck at the sheer scale of information available to them, and seek to assimilate it into building the grandest narrative possible. They try to generate a story in which all of the facts they have piled up make sense.

So what if an alternate reality game really did keep on going, if it had no end point? It would amount to a simulation of the world. All aspects of “reality” that fit into the simulation, including some produced artificially by players for fun and profit, would be incorporated. If the game had no boundary, at some point you could think that the world it is building simply is the world. In one early ARG, after the final puzzle had been solved, some participants winkingly suggested they next “solve” 9/11.

ARG game masters have described one of the pathologies of players as apophenia, or seeing connections that aren’t “really there” — that the designers didn’t intend — and therefore pursuing red herrings. In one game, in which players had to look for clues in a basement, some scraps of wood accidentally formed the shape of an arrow pointing to a wall. Players believed it was a clue and decided they needed to tear down the wall to find the next clue. (The game master intervened just in time.) But the difference between true and false interpretations exists only if the puzzle has one right answer, or one central authority — like J. K. Rowling intervening in fan debates about which Harry Potter characters are gay. The puzzle that today’s media consumers are trying to solve is the world, and interpretations are more or less up for grabs as long as they fit the story.

In a world in which we all play alternate reality games, we each pile up superabundant facts, theories, and interpretations that support the main narratives, and our allegiances gradually solidify as we consume and produce the game material. It’s not just interpretations of data that wildly diverge between different games, but also players’ sense of what is realistic or plausible — for example, their perceptions of the rates of homicides committed by police, or by illegal immigrants. This means that, in any crisis situation, the most narrative-enhancing reports will spread widest and fastest, regardless of whether they are overturned by later reporting. As L. M. Sacasas noted about the media experience of January 6, “a consensus narrative will almost certainly not emerge.”

The cynical reader might interject that the bygone era of mass media was not a golden age of truth, but was subject to its own overarching narratives and its own biased reporting. But what matters here is that mass media, rooted in an advertising business model and in broadcast technologies, created the incentives and capability for only a small number, perhaps even just one, of these narratives to emerge at one time. Both journalists and spin doctors attempted to massage or manipulate the narrative here or there, but eventually mass media converged on whatever the narrative was. In an age of alternate realities, narratives do not converge.

As the media ecosystem produces alternate realities, it also undermines what remains of consensus reality by portraying it as just one problematic but boring option among many. The process of arriving at this contrary view of the consensus — a process sometimes called “redpilling,” after The Matrix — goes something like this: A real-world event occurs that seems important to you, so you pay attention. With primary sources at your fingertips, or reported by those you trust online, you develop a narrative about the facts and meaning of the event. But the consensus media narrative is directly opposed to the one you’ve developed. The more you investigate, the more cynical you become about the consensus narrative. Suddenly, the mendacity of the whole “mainstream” media enterprise is laid bare before your anger. You will never really trust consensus reality again.

Opportunities for such redpill moments are growing in frequency: the 2016 presidential election, the George Floyd protests, masking and lockdowns, the crime wave in American cities. There were always chinks in consensus reality — think of the newsletters of the radical right or the zines of the leftist counterculture — but finding consensus-destroying information was costly. The process was unable to produce the real-time whiplash of today’s redpill moments. The speed at which events like these are piling up suggests that the change is structural, that it is the media ecosystem itself that is fundamentally transforming.

For our final game, please consider a troubling episode of dreampolitik from very recent American history.

Driven by devastation over the outcome of the presidential election, brought together by algorithmic recommendations on social media feeds, fueled by information overload, loosely organized by networks of influencers, egged on by massive ratings and follower counts, and strengthened in the loyalty that comes with telling an audience what it wants to hear, committed media game players created an alternate reality in which the good guys were working behind the scenes to bring down the bad guys. The story of secret activity that would end the hated presidency at any moment became detached from the actual government investigations underway, from verifiable facts, from discernible reality.

Is the paragraph above a description of …

a. How media members, powerful political actors, and ordinary people deranged by Trump bought into the now-discredited Steele dossier, which claimed to show collusion between Trump and Russia?

b. How media members, powerful political actors, and ordinary people deranged by Trump bought into the “Stop the Steal” lie, leading them to mob the United States Capitol building and try to overturn the 2020 election?

Pick one.

My argument here is not that we are all the way into Wonderland, or even close to it yet. But that qualification should be as worrying as it is reassuring.

The change I am outlining is in most parts of the media world still fairly subtle — the addition of a new valence in how we see actors interpreting information, sharing content, and choosing what to emphasize. The real world still exerts hard pressure on the narratives people are willing to accept, and the realm of pure fantasy remains that of a small fringe. Yet while game-like media habits are easiest to see and most pronounced in Q-world, we can already see some of the same activities, engrossments, and intuitions that are involved in playing an alternate reality game creeping into the broader media ecosystem too — even in sectors that pride themselves on providing the sane alternative, the lone voice of reality. The point here is not to draw a moral equivalence, or to say that all these actors have lost their grip to the same degree, but rather to suggest a troubling family resemblance. The underlying structure of the reality-gamesmanship we find in, say, Infowars has its counterpart in, say, Trump-era CNN: incentives and rewards, heroes and villains, plotlines, reveals, satisfying narrative arcs.

To be a consumer of digital media is to find yourself increasingly “trapped in an audience,” as Charlie Warzel puts it, playing one alternate reality game or another. Alternate reality games take advantage of ordinary human sociality and our inherent need to make sense of the world. All it takes for the media environment to begin functioning like everyone is playing alternate reality games is:

Internet brain worms thrive on these ingredients. As long as spending more time consuming media — whether Facebook, MSNBC, talk radio, or whatever — increases the strength of one’s exposure, the worms will find their way. Reality as we understand it is a phenomenon of social structures, language, and shared processes for engaging with the world. Digital media is remaking all of these in such a way that media consumption more and more resembles the act of playing an alternate reality game.

The recent rise of subscription newsletters on the platform Substack has provided a powerful if depressing natural experiment of this phenomenon. Freddie de Boer and Charlie Warzel, both widely read commentators, have written about tinkering with their own Substack content, finding that calibrating posts to engage with Twitter controversies of the day led to exploding levels of clicks and new subscriptions, while sober, calm content was relatively ignored. Writers who get their income directly from subscriptions have every incentive to provide red meat day after day for some particular viewpoint. Sensationalism is of course as old as the news itself, but what targeted media like newsletters provide is the incentive to be sensationalistic for niche audiences. There is a reward for spinning alternate realities.

When writing for niche audiences, more status accrues to sharing narrative-enhancing facts and interpretations than to sharing what most of us can agree is reality. Those who quixotically hold on to the TV-era norms of balance and fact-checking won’t find themselves attacked so much as bypassed. By a process of natural selection, attention and influence increasingly go to those who learn to “speed-run through the language game,” to borrow from Adam Elkus, laying out juicy narratives according to the incentives of the media ecosystem without consideration of real-world veracity.

Business analytics will continue to drive this divergence. To illustrate the pervasiveness of this process, consider the logic by which The Learning Channel shifted from boat safety shows to Toddlers & Tiaras, and the History Channel from fusty documentaries to wall-to-wall coverage of charismatic Las Vegas pawn shop owners and ancient aliens theories. Content producers have an acute sense of which material gets the most views, the longest engagement, and the highest likelihood of conversion into subscriptions. At every step, every actor has the incentive to make the media franchise more of what it is becoming.

It’s an alien life form.

– David Bowie about the Internet, 1999

It is tempting to believe that, sure, other people are headed into Wonderland, but not me. I can see what’s happening. What if, say, you are not online, or don’t even pay much attention to the news? Even if your picture of the world is determined mainly by conversations with friends and family, you will find yourself being drawn into an alternate reality game, based on the ARGs they are playing. These games have “network scale” — they are more fun and powerful the more people you know are involved. This is also why it is becoming more and more difficult, and unlikely, for people playing different games to even talk to each other. Indeed, a common conceit of some media games is that “nobody is talking about this.” We are losing a shared language. It is not that we arrive at different answers about the same questions, but that our stories about the world have different characters and plots.

It is increasingly undeniable, looking at revealed preferences, that people can come to value their digital communities, relationships, and realities more than those of “meatspace,” as the extremely online call our enfleshed world. “For where your treasure is, there your heart will be also.” Every year, consumers spend billions of dollars on skins, costumes, and other “materials” in video games. Digital “property” like cryptocurrencies and non-fungible tokens have exploded. People attend events, show up at rallies, and even take vacations in order to post about them online. Many users on Reddit last year spent thousands of dollars on shares in the seemingly failing video game retailer GameStop, some declaring that they were prepared to lose the money, to send a message and garner status and make great “loss porn.” Recently, a player annoyed at the way the U.K.’s Challenger 2 tank was modeled in a video game posted classified documents to a game forum to make his point.

More than money, some participants in alternate reality games are willing to risk their lives and freedom. Over the past few years, Americans deeply immersed in their online versions of reality, driven by the desire to either influence them or create content, have: broken into a military facility, murdered a mob boss, burned down businesses, exploded a suicide car bomb, and stormed the Capitol.

Those who have studied the past should not be surprised. The most contested subjects in human history have arguably not been land or fortunes, but symbols, ideas, beliefs, and possibilities. As much blood has been spilled over products of the mind as of the body. The growing dominance of the Internet metaverse over “the real world” is just the next step in the story of man the myth-making animal.

You do not have to surrender your commitment to facts to participate in an alternate reality. You just have to engage with one, in any way. If you are a user of digital systems, if you allow them to provide you recommendations, if you train them on your preferences, if you respond in any way to the likes, downvotes, re-shares, and comment features they provide, or even if you are only a casual user of these systems but have friends and family and people you follow who are more deeply immersed in them, you are being formatted by them.

You will be assimilated. ♠

← Essay 1. What Happened to Consensus Reality?

Essay 3. How Stewart Made Tucker →

Published online as “Reality Is Just a Game Now,” TheNewAtlantis.com.