As a child, Marcy was chubby. Her mom was struggling with her weight, too, but she took drugs to keep it down. Fen-phen seemed to work, but it made her cranky, so Marcy was not a fan. When Marcy was fifteen, her mom took her to the doctor and got her on something similar. Marcy hated how jittery it made her feel, so she quit. After that she tried every diet on the books. She got results, but they were always temporary. This went on for decades.

By the time Marcy started hearing about Ozempic, she was, to put it mildly, a skeptic. And not just of the drugs but of the whole scheme as she saw it: take the drugs or follow the diet, lose weight; go off the drugs or the diet, gain it all back.

Marcy is now the co-owner of a plus-size clothing store in Los Angeles. She’s come a long way in how she thinks about fatness. She eats well and is physically active, and her doctor has not flagged any problems like diabetes. And yet recently, when she was in charge of snack time at a children’s theater, she snapped at an overweight little boy who told her he was “starving” right after eating.

“Great, you already had a snack,” she said — and immediately regretted it. She wished that instead of assuming the kid was just going to overeat again, she had found him something that would satisfy his hunger.

Marcy isn’t the only person wondering how to help children who are overweight. In 2022, the FDA approved semaglutide, the drug sold as Wegovy for weight loss, for use in children as young as age twelve. Wegovy and its related class of medications, including Mounjaro, Zepbound, and Ozempic, are far from the first weight loss drugs on the market, but they are touted as the most effective.

Since then, President Trump has appointed Robert F. Kennedy, Jr. as the Secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services, and, informally, as leader of the Make America Healthy Again movement. MAHA claims that chronic diseases, including obesity, are best treated not with pharmaceuticals but through nutritious food.

The stereotypical member of the MAHA movement is a tech skeptic: a “crunchy con” mom who turns off her Wi-Fi at night to protect herself from electromagnetic radiation and drinks raw milk because she doesn’t trust the FDA on the benefits of pasteurization. She washes her clothes with Castile soap (too many lab-generated synthetic chemicals in Tide) and was a regular at the local farmers’ market before it was cool. She has bought into the idea of “organic” as not just a produce preference but a purer way of life.

But Kennedy plans to do much more than nag Americans about eating their veggies; he wants to ensure that the latest health tech is drafted into his movement. His goal is that within four years every American has a wearable health device that tracks metrics such as blood glucose and daily step count. “We’re about to launch one of the biggest advertising campaigns in HHS history to encourage Americans to use wearables,” he said in a Congressional hearing in June. “Wearables are a key to the MAHA agenda.”

It may be surprising at first that Kennedy is joining the techie side of America’s booming wellness industry. But in fact he’s not the only one: from Bryan Johnson’s attempts to follow the algorithm to immortality to Kennedy advisor and Surgeon General nominee Casey Means’s advocacy for clean eating and glucose monitoring to fix metabolic dysfunction, anti-establishment wellness gurus are increasingly pushing individualized health programs that present new technologies as magic bullets for Americans’ health problems. So while MAHA tends to bill itself as the antithesis to Big Pharma, recent trends under Kennedy’s HHS are turning the movement into pharma’s biggest competitor in the game of selling high-tech biohacks that promise to reverse America’s rising weight trends.

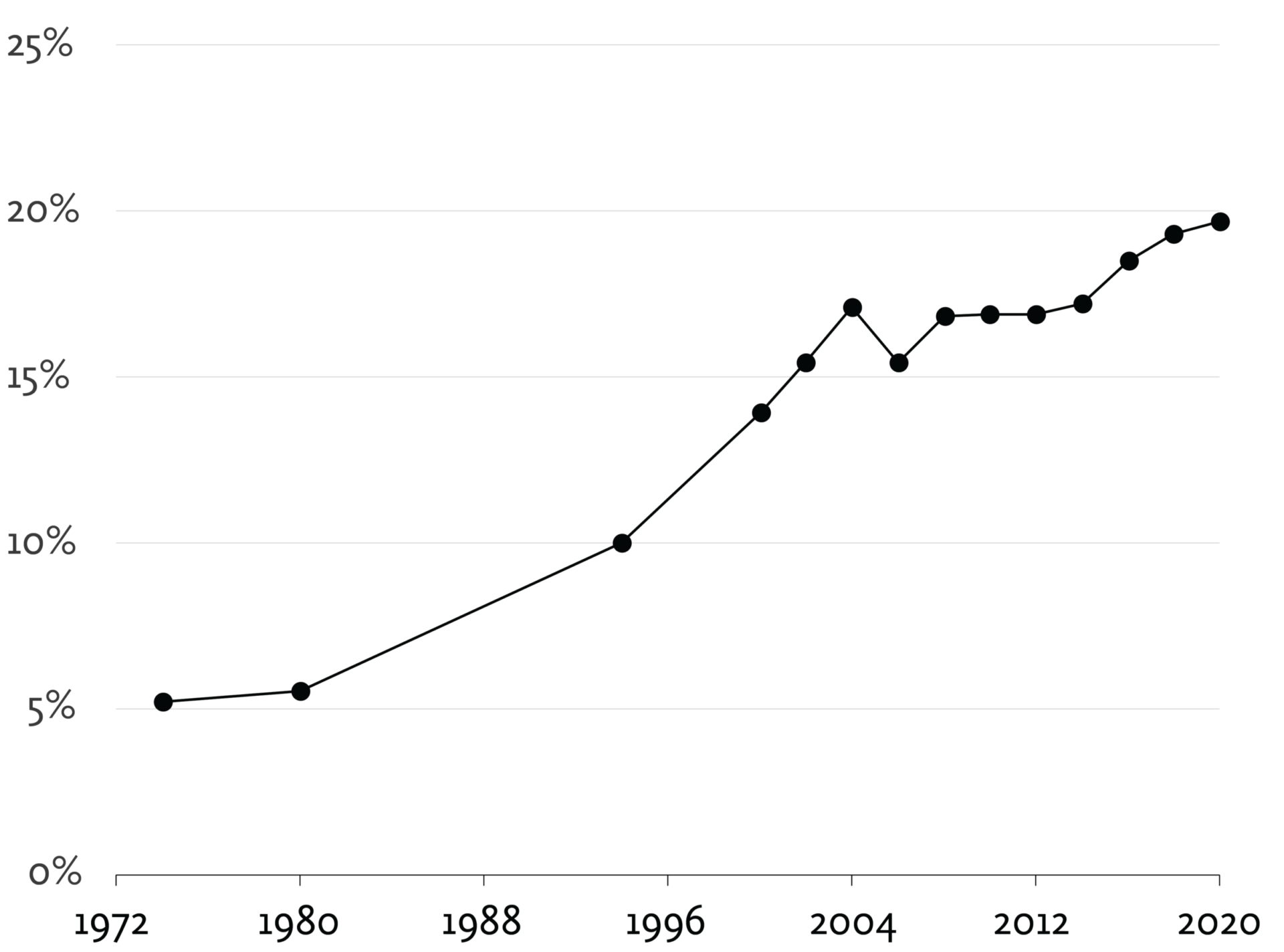

In a country where 20 percent of Americans under twenty and 40 percent over that age are obese, and in an economy where treatment for chronic diseases related to obesity costs hundreds of billions of dollars per year, finding and fighting the causes of obesity is one of the most important and high-stakes public policy debates of our time. The fact that for decades all attempts at reversing rising obesity levels have failed only makes the problem more pressing. And the fact that people are crossing the threshold for obesity ever earlier in their lives makes this one of those unavoidably anxious debates about posterity. Research suggests that genetics and early habits determine weight to a degree that makes it difficult to ever mitigate with later lifestyle changes. Today’s children are the first to grow up with both Wegovy and wearables, so they will be the final judges in the fight over which treatments actually work.

The two camps in the debate are divided on the answer to an old question. Which is more responsible for the problem: genetics or upbringing? Nature or nurture? If you say nature, then your solution is likely weight loss drugs. You believe that kids who are genetically predisposed to become obese will likely be and stay that way, and the new class of drugs could be a miracle in not just treatment but prevention. If you say nurture, then you may look to the MAHA movement not only to fix the system that is making Americans addicted to unhealthy food but also, increasingly, to empower them with technology that allows them to make better choices.

Though the chasm dividing these sides is vast, if you peer deep into it, at the bottom you may see common ground. Both are actually marked by forms of techno-optimism. Either drugs are going to save the kids — or “bio-optimization” and revolutionary organic farming practices will. Whatever the case, all we need is one weird trick to be healthy again.

If money could buy a solution to the problem of childhood obesity, it would be on display at the annual conference of the Obesity Medicine Association. This April, the conference took place at the expansive Gaylord National Resort in National Harbor, Maryland. National Harbor is all parking garages. The streets around the resort are filled with the kind of faceless franchises that exist in large part to kill the time of the tens of thousands of conference attendees spending down their company’s expense accounts every year: Nando’s, Ben & Jerry’s, McCormick & Schmick’s. The giant courtyard of the hotel has an entire indoor village with more ersatz establishments. A heavyset teenage girl, a middle-aged woman, and an older man, all positively glowing with health, smile down from a banner at least ten yards wide next to the registration desk. The banner’s label blares, “Wegovy.” There is no secret about who is backing this event.

In the corridor leading to the meeting rooms, more pleasantly plump people gaze reassuringly at me from standing signs. One sign lists the “5 Principles of Obesity”:

I note the polemical edge in that word “undeniable.” The question of how best to treat obesity is ostensibly under debate here, but the overall logic of the principles — if disease, then treatment — paired with the pharmaceutical advertising next to it seems to make the answer a foregone conclusion.

When I enter the first meeting room, I’m struck by the sheer size of the audience for this message. Attendance gives medical professionals a Continuing Medical Education credit for certification in treating obesity in their practices, and they have come in droves with their Yeti water bottles and North Face sweaters. Many are primary care physicians, nurse practitioners, and the like who are responsible for advising patients on weight loss. Much of the information shared here will end up being used in doctor’s offices across the country.

At the first session of the morning, Dr. Harold Bays, the president of a medical research institute in Louisville, Kentucky, discloses that he has consulted or contracted research for Eli Lilly (the maker of Mounjaro and Zepbound) and Novo Nordisk (Ozempic and Wegovy), along with Amgen, Pfizer, and a whole alphabet’s worth of others. Previous weight loss medications have had such bad side effects that they’ve been taken off the market, he says, but this new class of drugs, called GLP-1 agonists for the human satiety hormone they mimic, is a game-changer. They’re both more effective and less taxing on patients’ bodies than previous treatments.

Bays is optimistic about not just the current medications but the overall new approach to treating obesity. Other metabolic diseases, such as hypertension and diabetes, also once resisted being treated with medication. Now, medication is a standard part of what he calls “comprehensive” care for those conditions: lifestyle changes and dieting along with drugs. Before too long, he says, the same package will gain social acceptance as the standard of care for obese patients young and old.

GLP-1 agonists are the first in a wave of drugs that are increasingly capable of being personalized to do more than one thing: reduce appetite and fight nausea, for example, or preserve muscle tone during rapid weight loss. Bays fires off a barrage of these drugs: dual agonists, tri-agonists, muscle-acting agents. Trials are ongoing and long-term effects are unknown, but “we want the drugs now,” he says, because the results are so life-changing for patients. So he advises doctors to keep up with the news about the latest approvals and add them to the suite of medications they prescribe.

Despite all the talk of lifestyle modifications that should accompany weight loss drugs, doctors are often better informed about the drugs than the new lifestyles they are supposed to support. “A lot of physicians do not feel adequately trained to talk to their patients about nutrition,” says Dr. Nate Wood, a chef and the director of culinary medicine at Yale, in the second session I attend. In 1985, the National Academy of Sciences issued a report that recommended twenty-five hours of nutrition education for medical students, he says. Today, they get about eleven.

Wood offers some common-sense guidelines for patients both on and off weight loss drugs: focus on hitting protein targets, but don’t forget about that sleeper nutrient, fiber. Ninety-five percent of Americans aren’t eating enough fiber, he says, and patients on GLP-1 drugs are at risk of constipation because the drugs slow down their digestive systems. Most importantly, make sure patients are eating enough. He tells the story of one patient who gave a glowing review of her progress to one of Wood’s colleagues: “‘It is great,’ she said. ‘I’m not hungry all day. Yesterday, all I had was a small bag of popcorn.’ And you’re like, oh, gosh, that’s concerning.” The audience laughed sympathetically.

He advised setting a target of at least 1,200 calories a day to keep patients from dropping weight too fast and missing out on vital micronutrients. Suddenly it sounded like the drug was the disease and the food was the prescribed medication: doctors should watch dosage, symptoms, and the overall sustainability of the regimen. A treatment prescribed in large part to fix problems with food intake has actually created new problems with food intake.

And while it’s clear that Wood treats mostly adults, the stakes for children’s eating patterns when they’re taking GLP-1 drugs seem even higher. Children’s diets, more than those of adults, are made up of a majority of ultra-processed, low-fiber foods — some studies estimate up to two-thirds of what they eat. What happens if a child starts taking the drug and is now eating less, but not necessarily better? That could mean even fewer of the nutrients needed to sustain healthy growth, puberty, fertility, and so on. There are no long-term studies to either prove or disprove this, but sometimes the most sobering answer to hear from a doctor is “I don’t know.” And that’s often the answer when the question is “What about the kids?”

On the second day of the conference, I have no child care. So I strap my newborn to my chest and toss some crayons in my three-year-old’s backpack and show up to Dr. Claudia Fox’s session on “Empowering Comprehensive Obesity Care from Youth to Adulthood” with two daughters in tow.

Fox is an associate professor in the University of Minnesota’s department of pediatrics and the co-director of its Center for Pediatric Obesity Medicine. She paints a grim picture of childhood obesity treatment. In the past, she says, doctors followed a “wait and see” approach, monitoring children whose weight was high for their age and waiting to see whether it would resolve after puberty, when girls especially gain weight as their bodies prepare for childbearing. What they saw, though, was that “obesity in adolescents almost universally persists to adulthood.” In fact, the problem was evident even before puberty: “Ninety percent of three-year-olds with obesity will continue to have overweight or obesity in adolescence.”

According to Fox, doctors have been fooling themselves into thinking that obesity is more about nurture than nature: “Obesity is essentially baked into our DNA really, really early on.” And this has led to the lie that “lifestyle modification” can work for children, and has also fueled the shame that comes with children’s failure to lose weight: “I very deliberately say, when I’m seeing a new family, this is not your fault. This is not a willpower problem. This isn’t a parenting problem. This is a biological condition that’s primarily determined by our genetics.”

What to do, then? The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends that in addition to “lifestyle therapy,” “pediatric health care providers should offer obesity medications to children who are age twelve and older,” she says. “Notice that word ‘should,’” she adds. “They didn’t say you ‘may,’ or that you ‘could’ do it. No, you should do it.”

Fox says she’s aggressive about prescribing medication because she cares about curing kids. Think about cancer. “We would never be satisfied with just the stability of their leukemia,” she says. “We want them to be cured. We want resolution of their disease.”

“What is our goal for treatment?” she asks. “I think it’s still hard to say. With regards to treatment, our foundation, at least at this point, is lifestyle modification therapy.” But therapy is hard: research suggests that it takes at least twenty-six hours of lifestyle therapy — think food logs and tracking cardio — over the course of two months to a year to achieve significant weight loss. Vanishingly few patients manage this, or even have the potential to, given how little insurance will usually cover for nutrition therapy. That’s why “early intervention with the most intensive therapy available” — meaning GLP-1 drugs like Wegovy — “is really critical,” she says.

I listen in mounting dismay and then trundle my daughters out the door in search of a snack. We’re the lucky ones, too: my three-year-old’s favorite food is pizza, but her dad makes it for her from scratch. Her mom works from home and spends a significant amount of time persuading her to try spinach, cherry tomatoes, lychee, and tofu. And neither of her parents is overweight. Simply because of these early advantages, she’ll likely never face the problems that, according to Fox, many of her patients will struggle with all their lives.

The speakers at the OMA conference don’t misdiagnose the many challenges of obesity and the pressing concerns that arise as it presents itself earlier in people’s lives. Many of them are just surprisingly certain about its solution, given the dubious track record of past weight loss drugs in reversing rising levels of obesity. The exhibition hall reveals one source of that confidence: Novo Nordisk itself is here, and Eli Lilly, along with innumerable coattail-riders competing to sell their supplements in the attendees’ health care practices. And to do that they’ve brought bribes: boxes overflowing with sample shakes and probiotic drinks, free tote bags, and (deliciously) lollipops at vendor stalls selling healthy solutions for patients on weight loss drugs.

I let my three-year-old try a granola bar formulated for GLP-1 drug patients and then feel weird about it, less because I think it’s bad for her than because it looks like the kind of failing diet product I often see on grocery store clearance racks: highly processed, covered in questionable marketing claims, and likely to taste kind of gross.

After a presentation on “complex” GLP-1 treatment cases, I’m approached by a thirty-something woman in a bright pink pantsuit and kitten heels and a lanyard whose rainbow of ribbons displays a long association with the Obesity Medicine Association. No, she doesn’t do media anymore, she says, but she gives me her number and implores me to allow her to connect me with her babysitter. She adds as we part for the morning break that she hopes I’ll report fairly and acknowledge that obesity is, indeed, a disease — in case I’d missed the party line.

Even if that’s true, Ozempic may be less of a revolution than its promoters say it is. Who can afford it, in literal dollars or in years spent on the drug, possibly to end up right where one started if one ever quits? After all, an Oxford University analysis of eleven studies found that patients who stop taking GLP-1 drugs typically regain the weight within a year.

The fact that there’s not yet long-term data on the effects of these drugs for weight loss offers hope for the children starting to take them now. But it also means there’s no reason to assume they will work. Adolescents have ahead of them a whole life of navigating temptations, social pressures, genetic predispositions, economic obstacles, and all the other challenges that come with having to take care of one’s body in the long run. It’s how they manage those pressures that will determine much of the results of the Ozempic experiment.

Not long later, as I leave the lunch buffet, I’m approached by an employee from the resort. I’m holding two plates of chicken salad and two glasses of water and pushing a stroller with my hip while directing my older daughter to a table.

You need to leave, the woman says. Don’t you know that this event is not for children?

If you’re the kind of person who generally avoids medical conferences and big-box hospitals, you might find yourself attracted to an approach to obesity that, on its face, is the very opposite from that advocated by the Obesity Medicine Association.

The story Casey Means tells about her life is that of a fat kid gone right. As we read in her book Good Energy, she was born with a predisposition for weight problems because of her mother’s undiagnosed gestational diabetes and related health conditions, then packed on pounds during puberty. According to the “nature” narrative, she was destined to be overweight her whole life. But instead of further abusing her body with dieting or disordered eating, she turned herself into a health nut: she studied nutrition, taught herself to cook, joined a gym, and worked it all off. This knowledge turned out to be more useful than the curriculum at Stanford Medical School, where she became disillusioned with the health care system’s specialist, drugs-forward approach to treatment of disease.

She came to see an increasing number of ailments in her patients as not just related to but rooted in bad eating habits. Those habits were based on people’s ignorance about how they should fuel their bodies — and since each body is different, each person needs an individualized health plan, not a one-size-fits-most prescription. She found herself coming around to the “nurture” model regarding chronic diseases and obesity: our habits determine our health far more than our genes do.

She dropped out of her surgical residency program and co-founded a health company named Levels, which sells continuous glucose monitors (CGMs) and offers an app that tracks people’s blood sugar and thus helps them optimize their eating, exercise, and sleep. Last year, she published Good Energy: The Surprising Connection Between Metabolism and Limitless Health, which argues that malfunctioning mitochondria (the powerhouse of the cell, as you no doubt remember from middle school) are the cause of the majority of chronic diseases, including those related to obesity. The solution? Bio-optimization: eating organic and gluten-free to avoid toxins, strategically planning meals and sleep to minimize stress, and tracking it all with a CGM.

“We are entering the era of bio-observability: more readily available blood tests and real-time sensors filtered through AI analysis to give us a highly personalized understanding of our bodies and a personalized plan to meet each body’s needs with daily choices,” she writes.

It’s easy to see how this pitch is attractive to individualistic Americans, especially those who are already skeptical of the medical establishment. “You should not blindly trust your doctor and you should not blindly trust me,” Means writes. “You should trust your own body.”

The book was a No. 1 New York Times bestseller. It popped up in chiropractic offices and other alternative health practices around the country. Means and her brother, Calley Means, became top advisors to Robert F. Kennedy, Jr. and his Make America Healthy Again movement. And in May of this year, Means was nominated to be Surgeon General of the United States.

These are no longer the mere musings of an Instagram influencer and alt-health entrepreneur: the idea that “food is our most potent weapon against chronic disease” and that tech will help heal us is a serious competitor to the Wegovy weight loss model. In fact, this techno-optimist narrative is much bigger than Means — and much less mad than the prospect of going to bed at eight thirty and injecting one’s children’s blood to live forever, à la Bryan Johnson. The wellness industry — health products and regimens sold outside the typical health care pipeline — is larger than the pharmaceutical industry: an estimated $6.3 trillion per year compared to $1.6 trillion. It’s expected to reach $9 trillion in the next three years. Social media–mediated wellness and app-based health make up the water the next generation of health-seekers will swim in.

Much of what Casey Means proposes to do to fix our food system makes sense, especially for addressing the problems many Americans see affecting children’s diets. Her ideas: remove ultra-processed foods from school meal programs, ban food dyes that have been linked to behavioral problems, and redistribute Farm Bill subsidies from corn, soy, and tobacco to support fruits and vegetables, ideally organic.

Many critics have focused on her anti-pharma positions and speculated about the implications for vaccines and drugs like GLP-1 agonists. But beneath the crunchy-conservative advice about how to get kids to eat organic lies a techno-optimism strikingly like that of the pediatrician prescribing semaglutide to sixth-graders. “What if we treated humans like rockets, equipping them with sensors before systems fail, to understand where dysfunction is arising so we can address it?” Means writes in Good Energy. The metaphor is borrowed from Josh Clemente, her co-founder at Levels, who is an alumnus of SpaceX. Reducing food to its component parts, and eating habits to an “individualized” health plan, makes it easy to turn the human body into a machine.

Yet Means sees her solutions for chronic disease as not mechanistic but spiritual, in contrast to those of the soulless medical establishment. “Everything is connected,” she writes in her book. And the “spiritual crisis” of America’s chronic disease epidemic is “an assault on the miraculous flow of cosmic energy from the sun, through the soil and plants, through bacteria in my gut, through my cells’ mitochondria to create the energy that sparks my consciousness.”

This is why individualized tech is so much more promising for her than the old wait-and-drug medical model, which waits until people get fat and sick and then charges them to treat their symptoms. “We have the potential to live the longest, healthiest lives in human history, but this will require optimization,” she writes.

And it has to start young. The “natural” alternative to the medical establishment’s drug-first model turns out to draw on the same assumptions as not just Wegovy but the failed weight loss cures that came before it: your body is a problem, and there’s a product that can solve it if you start early enough and work at it hard enough. Bringing parenting into the equation shows how this pitch can be less freeing than it seems. After all, the earlier you optimize, the better off you and your children will be. Mothers should start optimizing their children in utero, since everything Mom eats also feeds baby.

It’s hard to give up the idea that weight loss is a matter of personal responsibility: of finding the right hack to fix it, with a drug or a gadget or with pure grit. And it’s easy, when one tries to give up that idea, to fill the void with a dream that ultimately follows from the same assumptions. Means’s story, then, is not that of a fat kid who found the true fitness gospel. Or if it is, it’s the same old story: she is one of the few lucky people who found salvation through weight loss and now has the difficult task of trying to share it. But solutions tend naturally toward the one-size-fits-all, while crises tend, unfortunately, toward complexity.

The danger of techno-optimist solutions is that they treat the same thorny problem — stubbornly rising weight at younger and younger ages — with the same old solution: now there’s a drug, or an app, for that. The problem is not that these solutions are bad, or bound to fail. It’s that they’re utopian. What they are both selling is the idea of a simple fix for all the problems with food and health that contribute to obesity. This is a recipe for disappointment.

Many patients come to Dr. Siham Accacha looking for the simple fix they’ve seen in all the ads recently: they want to be prescribed a GLP-1 drug. Like the doctors at the conference, Accacha, a pediatric endocrinologist at Cohen Children’s Medical Center in New York, is willing to prescribe it. “I try to present it to them as a help, as an extra motivation,” she says.

But she warns them that a lifetime on medication, despite what the Ozempic ads suggest, is likely not realistic or desirable. “They have the opportunity,” she says, “to actually go to the next step, to lose weight, but also to learn how to eat healthier because it decreases their appetite significantly.”

Accacha tells me that her experiences with patients show that the causes of obesity are not as simple as nature or nurture alone but stem from something like culture: the framework of habits that exist outside an individual or family and guide people about what eating and living are good for in a larger sense.

A major part of the problem is the conflation of junk food and childhood: “There is this belief that the kids are kids and they should live like kids, and eating bad food is, you know, it’s fun,” she says.

Accacha argues that teaching people how to eat still offers the best shot at beating obesity before it starts. But that education has to begin earlier. “We don’t wait until we are adults to learn mathematics. You start young. And if that is ingrained in your brain and you learn how to eat healthy and you learn that you have to exercise, it becomes part of your life, so then it’s less effort as an adult to have to deal with this problem.”

“And it might not be enough,” she adds. “I don’t know. I don’t pretend to have all the answers.”

That’s because there is no single answer. Both the medical model and the food-as-medicine alternative isolate one aspect of the problem of childhood obesity and call it the root of the disease. But in reality roots form in networks: genetics, eating habits, the quality of the food system, bad information, poverty, ignorance, unrealistic goals, and good old-fashioned despair.

As Marcy sees it, the deck is stacked against her. According to the “nature” crowd, she was destined to be fat and so weight loss drugs should be her greatest hope. According to the “nurture” camp, the responsibility for every pound of her weight, and eventually that of her children, now lies squarely on her.

“I’m not healed enough to train up a little person on how to eat and how to fuel their body and how to feel healthy and whole in it,” she says. “I’m child-free by choice.”

Techno-optimism, when it fails, devolves into pessimism. Quests for impossible ideals like that of perfect health have a way of being abandoned. This is all the worse for those who come after us, who deserve that their lot be not perfect, just better.

Exhausted by science and tech debates that go nowhere?