When Jack Kevorkian set out for California in 1976, he had every intention of leaving medicine behind in Michigan. The last two decades had been ones of disappointment and defeat. He was nearly fifty, unmarried, and stalled out in his career as chief pathologist at a large hospital in Detroit. So, like many others facing midlife crises in that hangover decade, he packed up his few belongings and headed west to devote himself to art.

His idea was to adapt Handel’s Messiah for the big screen. Kevorkian knew next to nothing about filmmaking, but he loved the music passionately. For the next few years, he worked on the project — a frustrating, mentally isolated period in which his passion gradually gave way to a deeper and more consuming obsession. California changed him, and when he returned for good to his home state in 1985, he no longer thought in terms of recitatives, choruses, and arias. Death alone was on his mind.

Kevorkian soon turned his fixation into a medical crusade. He had long believed that the seriously ill should be permitted to end their lives whenever they wished. Further, he held that doctors should feel compelled to assist them, and, moreover, to assist society more broadly by using their organs for the benefit of medicine. By the late 1990s, Kevorkian had aided in the deaths of more than a hundred people and, through a series of highly public trials, become a national celebrity. His ad hoc medical practice was cut short in 1998, when he was arrested after going on 60 Minutes with a tape of himself euthanizing Thomas Youk, a middle-aged man diagnosed with ALS. By that point, however, Kevorkian had become one of the great sensations of the late twentieth century. In hindsight, we can say he was much more than a sensation. He precipitated a change in public opinion on assisted suicide: for now over a decade, the majority of Americans have considered the practice morally acceptable.

Kevorkian died in 2011. Since then, his personal and professional papers have been housed in the University of Michigan’s library system. I read through them all — every letter, medical record, annotated manuscript — over the course of a snowed-in week in Ann Arbor in February 2025. What I came to see was a man who spent his entire adult life thinking about death. He gradually worked his way to the conclusion that anyone who desires death should be permitted to access medical assistance to reach it. And, unlike most other assisted suicide advocates, he took action. His own record of his career is, like many bodies of madness, surprisingly coherent when considered on its own terms.

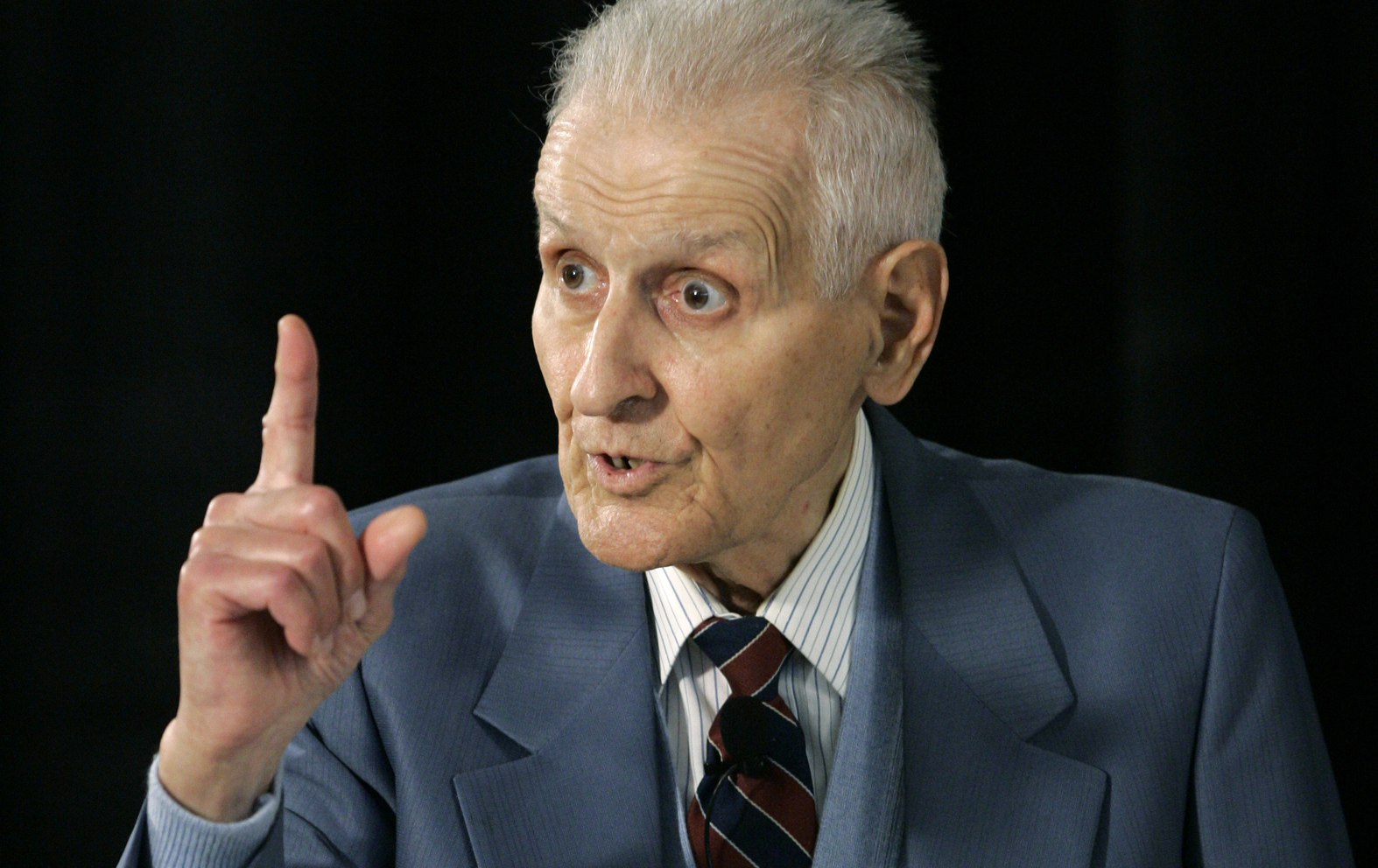

The doctor may have been a crank, but he was a highly charismatic crank — a prophet. It was a role he had been rehearsing for, perhaps unknowingly, those lonely years in the desert. While his Messiah ended in failure, Kevorkian’s own public ministry has been a lasting success. To understand the world he wrought, we must behold the man.

Jack Kevorkian was born in Pontiac, Michigan, in 1928, to Armenian parents who had fled the genocide at the hands of the Ottomans during World War I. He was always considered bright. He graduated with honors from his public high school and took a degree in clinical pathology at the University of Michigan. But he was also considered odd. He was forever running perverse experiments. In the course of his wide reading, he came across an ancient Greek practice in which condemned prisoners were dissected alive for the purpose of scientific study. He wondered if advances in anesthesiology and organ transplantation might make a modern version of this procedure at once more practicable and useful. He wrote a scholarly article suggesting that the experiment be tested on death-row prisoners, and in 1958 delivered it as a lecture in Washington, D.C.

The lecture attracted unwelcome attention to the University of Michigan, and Kevorkian was given a choice of abandoning either his line of study or his post at the hospital. He chose the latter and finished his residency in Pontiac, where, free from the rigors of Ann Arbor, he indulged in ever more bizarre beliefs. He became convinced, for example, that the blood from warm cadavers could be successfully transfused to living bodies, a procedure he argued would be useful for troops on the battlefield. He applied to the Pentagon for research funding and was denied. So he took matters into his own hands. Along with his friend, Neal Nicol, with whom he would later collaborate in his “medicides,” Kevorkian performed the experiments using the bodies of car crash victims that rolled into the hospital and others who had suddenly died. His methods were primitive: Kevorkian hooked up an IV line to the body on one end and to the recipient on the other. Then he tilted the table and let the blood flow from the dead vein to the living one. The experiments were successful — sort of. In one of them, in which Kevorkian served in a control group receiving blood from a blood bank, he contracted hepatitis C, a disease that afflicted him for the rest of his life.

He soon quarreled with the leadership at Pontiac and quit. He bounced around Detroit for the next decade, bringing unorthodox practices and outlandish medical ideas wherever he went. He eventually landed at Saratoga General Hospital, on the east side of Detroit, where he became chief pathologist. This was the peak of Kevorkian’s formal medical career. And he was miserable. His fellow doctors all thought he was a kook, and his private life was a mess. He broke off an engagement. Medicine, which had long sustained him, lost its appeal. His whole adult life he had tried to be a daring, trail-blazing doctor. Nobody seemed to appreciate his efforts. So he took up painting. He wrote philosophical treatises. He bought a concert organ and taught himself to play Bach.

In short, Kevorkian was staring down middle age. Others in his situation were throwing over their old lives and starting anew — or at least buying sports cars and getting divorces — and he too was caught up in the frenzy. Adapting Messiah for the screen may seem like an odd way to have a midlife crisis, but for Kevorkian it made sense. Although he had abandoned religion at a very young age, he did not need to believe in God to be captivated by the Baroque oratorio. Christ’s suffering, death, and resurrection appealed to him as a heroic, lonely struggle. Kevorkian resigned at Saratoga, loaded up his Volkswagen van, and drove west.

Kevorkian began work on the film in the summer of 1976. He toiled alone, and progress was slow. In his letters to his sister Margo, who later was to be his primary confidant and collaborator in his assisted suicide practice, he attempted to sound optimistic. That July, he reported that he would soon have about a quarter of the film ready for editing. Much of the material was pulled from unused archival footage in Hollywood film libraries. Kevorkian did not have the budget — nor the manpower — to dream up an epic on the scale of Ben Hur, so he had to settle for second best. Even second best, he admitted, was nearly beyond him.

A few experienced stagehands took pity on Kevorkian and helped him to scout outdoor locations and to fake grandiosity on vacant soundstages. Others lent him their expertise in filming and lighting. Kevorkian designed the costumes and hired a local seamstress to sew them into convincing first-century robes.

As for the actors, some of the parts Kevorkian filled himself. “We needed an actor as a prophet,” he wrote to Margo. “Yup. Me. I donned a robe, sandals, and started to mime. We viewed the takes a couple of days later. They’re beautiful.”

Kevorkian may have been satisfied with his work, but even he admitted that film production was wearing him down. For the prophet scene — the “O Thou That Tellest Good Tidings to Zion” aria in the oratorio’s first part — he had to put on a robe in the summer heat and climb a mountain. It took half the day to get five minutes of usable material.

Delays such as these bothered Kevorkian. Although he wrote to Margo that he was “not at all homesick” and “too busy and on too important a project for that,” in his mind he was already returning in triumph. He planned to buy a Buick and take it cross-country later that summer to New York, stopping in major cities along the way as a makeshift form of distribution for a December film opening. Once in New York, he planned to catch a flight to West Germany to schedule European showings. A former colleague at Saratoga had told him that his wife’s German father owned three theaters in Frankfurt, and that a friend owned a chain of Midwestern movie theaters. Kevorkian believed that his casual proximity gave him an “in” with the business.

What could have been running through his mind? The wave of New German Cinema was cresting in the late Seventies. Wim Wenders, Rainer Werner Fassbinder, and Werner Herzog were all making their best work. How could a first-time director cobbling together a film from B-reel possibly hope to match them? “Europe should be a superb market for this film,” he boasted to Margo, “especially Germany.”

By August, however, Kevorkian’s enthusiasm had cooled. He was still picking out shots from the film libraries — “great scenes from big Hollywood productions which I couldn’t hope to duplicate” — but faced the impossible problem of finding the right person to play Jesus Christ. Kevorkian worked fine for an actor in the Old Testament parts: his careworn, gaunt face gave him a certain gravitas. But Christ was another matter entirely.

He hoped to wrap up filming in September, finish editing in October, and be ready for a Christmastime opening. As it stood, the film was in danger of going over budget. He needed to hire about twenty extras for crowd scenes and rent out a garden in Long Beach to fill in for Gethsemane. And yet he was still confident, or at least he faked it. “Those who know ‘Messiah’ think it’s great,” he wrote to Margo. “Feel OK.”

Of course, nothing ever goes according to schedule in film. The months dragged on, and by June 1977 Kevorkian was still editing. His money had run out, and he was living in reduced circumstances. When he first went out to California, he had rented a small apartment. Now he was squatting in his Volkswagen. He stopped making phone calls; writing letters was cheaper. He complained to his sister that post-production costs were adding up. He had scratched the negative and needed to pay to fix it. He also had to pay for color and density balancing. And on top of it all, he had to wait a whole extra month to see if the additional work even came out correctly. He said he was looking forward to taking another booking trip across the country. He had no plans after the summer.

“Will ‘play it by ear’ until the booking trip is over,” he wrote. “Then will decide where to settle and work.”

Kevorkian would “play it by ear” well into the 1980s. Even he must have known that the film was nowhere near finished. At one point, he showed the trailer to Neal Nicol, who, a loyal friend, refused to disparage the desperate work outright. It showed Joseph and the Blessed Virgin Mary, as well as a few shepherds at the nativity, along with stock footage stuffed in wherever Kevorkian had the chance. “Kind of a disjointed presentation,” Nicol remarked later.

About the same time that Kevorkian’s work on Messiah began to falter, reports in the national news revived his old fascinations. In 1976, the Supreme Court heard Gregg v. Georgia, a landmark case in which the court reversed the de facto ban on the death penalty that it had imposed four years earlier in Furman v. Georgia. The following year, the state of Utah carried out the first execution since the ban. In the next few years, thirty-five states reinstated the death penalty. Public opinion shifted, too. At the beginning of the decade, not even a bare majority favored the death penalty. By its end, nearly two-thirds did.

Kevorkian followed the changes with interest. In the Fifties, before he delivered his disastrous lecture, he had personally canvassed death row prisoners in Ohio to gauge support for his organ transplantation research. But the following two decades of disappointment, both personal and professional, had persuaded him to shelve his proposals for a more favorable time. By 1982, it appeared that that time had come. Ronald Reagan was president, and it seemed like anything was possible. Not that Kevorkian was a Reaganite. He considered himself a strict civil libertarian, but in truth his political beliefs were incoherent. There was only one political issue that really mattered to him. And, as more states reinstated executions, Kevorkian’s mind once again turned deathward.

That same year he drafted a form letter outlining his old proposal, updated for the new political moment. He was living in a tiny apartment in Long Beach, working part-time as a pathologist. His filmmaking faded into the background, and his political activities took precedence. He sent his form letter to anyone he thought might be sympathetic. He tried governors, state legislators, Reagan himself. He wrote to Margaret Thatcher in England and Sheikh Ahmed Zaki Yamani in Saudi Arabia. He even pitched a profile of his idea to 60 Minutes. The producers turned him down.

The gist of the letter was always the same. Kevorkian was at heart a polemicist, and he wrote in a manner that, as the critic Gary Indiana would later observe, exuded “the excited pedantry of an adolescent autodidact.” After making clear that he was “absolutely neutral” on the subject of the death penalty, Kevorkian wrote that if it is to be used, it ought to be done so for the purposes of medical research. Then, after excoriating his perceived opponents, he rehearsed an argument that he would re-employ in a slightly modified form when making the case for assisted suicide: “It’s time that we offer condemned human beings the same opportunity for a fruitful death now reserved for, and foisted involuntarily on, innocent and arbitrarily condemned animals in our research laboratories,” he wrote.

Further, he added, “there are competent and qualified medical people who are willing to conduct experiments. They will not be executioners. Their aim will be to learn from an anesthetized human’s body.” By “they,” of course, he meant himself. Had he his way, once the body was sufficiently sedated, he would perform the experiments. After he left, a state-employed executioner would administer an overdose of the anesthetic — “the serenest possible death.” Not only was his method humane, he concluded, it also offered medical researchers a “priceless opportunity which all the money and technology in the world can’t offer.”

More often than not, Kevorkian’s letter failed to produce a response. There was no reason it should. Government offices receive hundreds of outlandish letters every day. Few make it to anyone of consequence’s desk. The furthest most make it is the trash can.

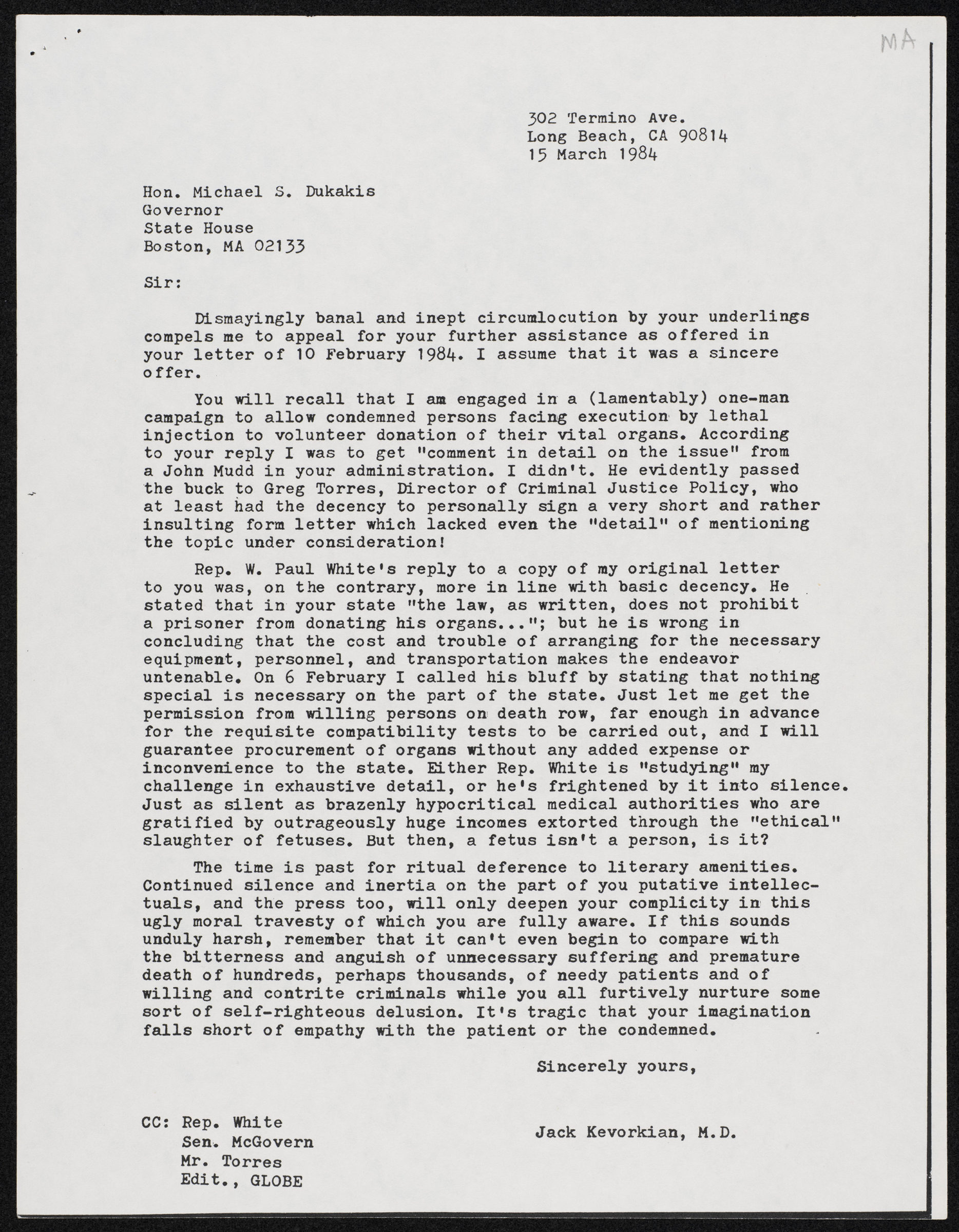

When Kevorkian did receive a response, without fail he squandered his opportunity to get a serious hearing. A case in point is his rather one-sided correspondence in 1984 with the governor of Massachusetts, Michael Dukakis. Kevorkian originally sent Dukakis his form letter in 1982 and received no response. But when Massachusetts took up the death penalty question in 1984 — Dukakis opposed its reinstatement — Kevorkian wrote to him again, reiterating his proposal.

A month later, Kevorkian received a brief reply, signed by Dukakis. It stated nothing and promised nothing: “I appreciate your taking the time to write to me. If I can be of further assistance, please let me know.” But Kevorkian acted as if he had got hold of the governor’s ear. When, shortly afterward, he received a curt reply from the director of criminal justice policy in the state, which only acknowledged that Kevorkian’s ideas were “being given careful consideration” — meaning, ignored — the doctor flew into a rage, addressing another letter to the governor and accusing his whole staff of malfeasance.

“Dismayingly banal and inept circumlocution by your underlings compels me to appeal for your further assistance,” Kevorkian wrote to Dukakis. “I assume that it was a sincere offer.”

He then recited his familiar whinge, before begging to try his experiments on a condemned man: “Just let me get the permission from willing persons on death row, far enough in advance for the requisite compatibility tests to be carried out, and I will guarantee procurement of organs without any added expense or inconvenience to the state.” Kevorkian concluded by insulting the governor and his staff — “you putative intellectuals” — and implied that the governor held a double standard by supporting abortion — a position which incidentally would harm Dukakis when he ran for president in 1988 — while opposing ethical research on the living bodies of the condemned.

“If this sounds unduly harsh, remember that it can’t even begin to compare with the bitterness and anguish of unnecessary suffering and premature death of hundreds, perhaps thousands, of needy patients and of willing and contrite criminals while you all furtively nurture some sort of self-righteous delusion,” Kevorkian concluded. “It’s tragic that your imagination falls short of empathy with the patient or the condemned.”

A performance such as that was sure to receive no reply from the governor, but it did merit a response from a state representative who had been copied on the whole chain of letters. “A copy of your vitriolic, insulting correspondence … has reached my desk. Since it appears that you are more interested in verbal posturing than anything else, I wish to acknowledge receipt of same and nothing more,” he wrote. And that was the end of it.

Even when elected officials, sympathetic to Kevorkian’s cause, attempted to help him, he was intransigent. An Indiana state senator, upon receiving Kevorkian’s form letter, wrote back: “May I suggest that as you solicit support around the country you change the belligerent style of your correspondence. You will find that if you are seeking the cooperation of legislators you will more likely obtain it by a less strident approach.”

The friendly suggestion drew a bloodthirsty response from Kevorkian. “Your admonition flimsily veiled as a ‘suggestion’ is out of order: I am not soliciting support or cooperation from legislators; I’m DEMANDING ACTION!” he replied. “Your collective fingers are on the trigger for it, and they’ll be drenched in the blood of many suffering and dying patients if you persist in unjustifiable procrastination, — especially because of procedural decorum.”

Kevorkian was just as hopeless in rallying the support of the medical community. Doctors were less likely than politicians to ignore him, but they were also unlikely to commit to ideas that might imperil their own careers. And, in almost every case, once they became engaged in correspondence with Kevorkian, they quickly incurred his wrath. An instructive case is his exchange with George Wald, one of the winners of the 1967 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for his discovery of the inner workings of the human eye. When Wald, who was already known for his histrionic public pronouncements, received Kevorkian’s form letter in 1984, he fired back in anger:

The kind of experimentation you are so anxious to undertake with condemned prisoners was indulged in wholesale by physicians and surgeons under official sponsorship under the Nazi regime in Germany and by Japan in World War II. Would you care to explain to us or to the California legislature the benefits to humanity at large, the advances in medicine and surgery that resulted?

I not only repudiate completely the barbarities you are proposing; I am equally shocked by the hypocritical cant with which you propose them. Frankly, I think you are a wretched person.

You bear an Armenian name. It is curious that next week I leave for Paris to serve on an international tribunal to review and pass judgment upon the genocide practised by Turkey upon the Armenian people in World War I. Think of all the medical breakthroughs one could have accomplished by not just killing them, but doing it usefully, for humanity.

Shame on you!

Kevorkian, understandably, took great offense at this response and shot back at Wald with vitriol:

If you can’t see the complete difference between what I’m proposing and what the Nazis did, then you’re doing a pretty convincing imitation of a hopeless imbecile.

And your parting “cheap shot” with regard to the Armenian massacres was especially despicable. Your attitude exemplifies perfectly the sinister phoniness so rampant in Western “civilization” which helped foster that horror and which guarantees perpetuation of its tragic consequences.

In the meantime, Kevorkian’s hopes that Messiah would ever see the light of day had been declining. Gradually he had given up his art — his paintings, his instruments, and his film reels — and stashed them in a storage locker in Long Beach. Then, suddenly, they got lost and he was left with nothing but the poster for Messiah, a purple and white affair set in gothic type and featuring Jesus hanging upon the cross, casting a long shadow over the world.

Kevorkian’s formal medical career was over and his artistic ambitions were dashed by fate. All he had left was his activism, for which he received no hearing. He was left on his own. Like the lone prophet on the mountain, he trudged forward with nothing but faith to guide him.

Kevorkian traveled between California and Michigan for the next year or so, moving one failed life back to another failed life. He read deeply, wrote much. In 1987, he traveled to the Netherlands, where he had discovered the work of doctors who were pioneering what was to become the European assisted suicide movement. He learned their methods, became fascinated. He had been looking in the wrong place all along. To perform his medical experiments, he didn’t need someone who was condemned to die; he only needed someone who wanted to die.

The same year, Kevorkian met in Los Angeles with Derek Humphry, the founder of the modern American assisted suicide movement. He returned to Michigan encouraged. Soon his ads in the newspapers appeared. Slowly, the patients began arriving. Two years later, Kevorkian wrote to Humphry, “I have resumed the project of helping patients die.”

The rest is well known. In 1990, Kevorkian assisted in the death of Janet Adkins, a woman from Oregon who had recently been diagnosed with Alzheimer’s. He was charged with murder and the following year the state revoked his medical license. The charges were dropped, but the case made him a celebrity overnight. Many more patients would follow — as would five trials — before Kevorkian was convicted of second-degree murder in 1999 for euthanizing Thomas Youk. He served eight years in prison. He was released in 2007 and ran for Congress the next year in a sensational but longshot campaign. When he died in 2011, it was of natural causes.

Kevorkian was never a member of any formal movement. Yet his work did more than anything to make assisted suicide a subject of popular debate in the United States. When he placed his first ads in the Detroit papers in the late 1980s, assisted suicide was not legal in any state. By the time of his death in 2011, three states had some form of legal protection for the practice. As of this writing, eleven states and the District of Columbia have it on the books. But more than modest legal successes, Kevorkian’s success was in eventually bringing a majority of the country around to his view: that “every legitimate medical service must be available to any and all human beings” — and that assisted suicide was one such service.

But Kevorkian’s papers in Ann Arbor reveal a more fundamental success. The popularization of assisted suicide, while important to Kevorkian, was only a proximate end. Throughout his work, beginning with his youthful experimentations, Kevorkian’s goal was to expand the horizons of what was medically acceptable in scientific research. For his own part, he earnestly wanted to harvest organs from one of his patients for transplantation. It didn’t matter if it came from a condemned prisoner, someone diagnosed with Alzheimer’s, or a perfectly healthy middle-aged woman. Kevorkian viewed the body the way a mechanic looks at an engine, as a machine meant for tinkering, rejiggering, adjusting. It was his prerogative to do with it what he pleased.

Of all his views, this one has proved the most influential. Belief in it is the foundation not just of the assisted suicide movement but of every life-extension project, biohacking scheme, embryo-selection lab — every attempt to fix the human body as if it were a machine in need of tuning. Kevorkian foresaw it, embraced it, and spread the good news with uncommon zeal.

And in his own cracked way, he remade the world in his image. Jack Kevorkian’s Messiah is the story of his own life. He is Handel’s lonely prophet, ascending the dark mountain of death, gesturing wildly in his homemade robes as a mezzo-soprano in the background draws out the words of Isaiah in a long refrain:

Behold your God

Behold your God

Behold your God.

Keep reading our

Winter 2026 issue

Dinergoths • Empty cities • Obesity wars • Killing sports • Subscribe

Exhausted by science and tech debates that go nowhere?