In the fall of 2018, a man named Akihiko Kondo married a doll named Hatsune Miku — not a doll in the figurative sense of a beloved woman, to be clear, but an actual plush doll, with long turquoise hair. The doll was the physical version of a computer-generated pop star created in 2007, who performs online, and “live” on real stages as a hologram. The bride wore white, and Mr. Kondo a matching tuxedo.

Their union is in many respects a symbol of the stresses facing marriage today, and a harbinger of what is to come. Across the industrialized world, marriage rates are plummeting. In Japan, where Mr. Kondo despaired of finding a human spouse, marriage rates fell from 9.3 per one thousand inhabitants in 1960 to just 4.1 in 2022. In the United States, they fell from 8.5 to 6.2 over the same period. And although birth rates are no longer linked as closely to marriage as they once were, they fell even more precipitously: again over the same period, the crude birth rate in the United States — the number of live births per one thousand people — dropped from 23.7 to 11.0. Even sex has become scarcer, with trends in sexlessness rising in recent years, and Millennials reporting fewer sexual partners than their parents and grandparents did at the same age.

As the data on these trends have become better known, researchers, pundits, and politicians have proffered a wide array of possible causes. Maybe marriage rates are falling as women’s rights and lives are improving, or as working-class jobs have disappeared for millions of single men. The decline could be attributable to fading morals, more promiscuous sex, or simply changing preferences. Maybe, having seen the escalating price of the traditional American union — the house, the kids, the college tuition — young people are deciding it’s simply not worth it. And so they’re striking out, and staying out, on their own.

All these explanations are no doubt true. But ultimately, the underlying force that is rearranging the contours of marriage is technology. This is most obviously the case with Mr. Kondo and his digital bride, and with dating apps like Tinder and reproductive technologies like IVF. But it is in fact nothing new, or even recent. On the contrary, marriage has always evolved along with changes in the ways we make goods and services — changes in what Marx labeled the “means of production.” And it has always tracked and supported the broader changes that sweep across societies in the wake of technological change. As the costs and benefits of interpersonal relationships shift, the realms of marriage, family, and sex are slowly but inevitably transformed as well.

Marriage, after all, is a contract. It always has been. Mostly devoid of what we now think of as romance, and stripped of gauzy veils and flowery aisles, marriage was originally a way for our nomadic ancestors to cement relationships of protection in far-flung lands. As these groups settled into agriculture and became dependent on a new set of tools, marriage became a means for vulnerable clans to produce the labor — meaning children — that they needed to farm their land, and to preserve it for future generations. Marriage changed again during the Industrial Revolution, as successive waves of urbanization moved income producers from the field to the factory and reduced the economic value of children. And marriage is changing rapidly now, as the acceleration of several technologies — including online dating, assisted reproduction, and artificial intelligence — is once again reordering the terms of its underlying bargain.

As these latest technologies evolve, they will almost certainly remake marriage in their wake as well. They will change how individuals meet, how they mate, and how they define their roles and responsibilities within the family. More specifically, the bargain that once defined marriage has now largely been rendered moot: women don’t need husbands to provide economic sustenance, or even to have babies; men don’t need wives to have sex, or to run the household. And all of us can find companionship outside the nuclear family. So marriage doesn’t mean, or bring, what it once did. It’s not primarily an economic equation anymore, or even necessarily a reproductive one. Instead, what remains is simply — but hugely — an exchange of far simpler and more sacred goods: love, commitment, and fidelity.

Most of us are unlikely to wed dolls. But understanding how even more mainstream unions are liable to evolve over the next few decades means digging into the technological foundations of marriage, and recognizing the ways in which the tools of a society’s production shape its most intimate relationships.

Once upon a time, marriage seems to have been a rare institution. Although archaeological evidence from this period is sparse, historians of marriage like Stephanie Coontz and others suggest that our earliest ancestors lived transiently and communally, moving from place to place in search of food and spending their short lives in groups of about two or three dozen people. Women bore children with the men of their group, but these pairings were fleeting and non-committal, and children had no particular connection to their fathers. Indeed, ownership of any form was foreign to these nomadic folk, whose possessions were limited to the bare necessities of what was required to catch and cook their food. When arranged mating did occur, it took the form of trades between neighboring bands, who exchanged young men or women as a way of creating new ties. The bride and groom were treated essentially as mutual hostages, and any children that emerged from their union were simply absorbed into the tribe.

Then, sometime around 8000 b.c., in fertile pockets such as the Tigris and Euphrates valleys and the banks of the Nile River, nomadic groups began to settle down, replacing their diet and lifestyle with more permanent, grain-based agriculture, and developing the tools — plows and carts and harvesting implements — that enabled them to grow food rather than simply gather it. Over time, the people of these early civilizations built homes and storage sites, and accumulated goods — private property that had to be accounted for and maintained. And thus humanity’s first settlers now needed their children both as laborers and heirs. This meant that they also needed to create a property right of sorts in their offspring, a way to differentiate which children belonged, not to the tribe anymore, but to two of its specific members.

For women, this identification was of course easy. But for men the options were limited. In fact, the only feasible way for a man to confirm the identity of a child as his was to produce that child with a certified virgin and guarantee her fidelity forevermore. This was the equation that produced the transaction of marriage. It was a straightforward exchange between a man and the woman who would become his wife. She gave him her virginity, fidelity, and the prospect of fertility; he provided a lifetime of economic support and a promise that his property would eventually be passed to their children. In many early societies, a widow was also obliged to marry one of her husbands’ brothers or remain single, since any subsequent children might create inheritance disputes for existing heirs.

It’s easy to interpret these regulations as controls on women’s sexuality, as early evidence of prudery, or misogyny. To some extent they were. But it’s also important to see that they were more centrally about wealth, not only for those who were in the process of accumulating it, but also for those clinging more precariously to the edges of survival.

In these emerging agricultural societies, land was fundamental to life, providing wheat or rice for sustenance and grazing areas for livestock. Successful harvests took time to produce, and bountiful ones created the surplus that enabled families to trade or save for leaner days. Holding on to land, therefore, became vital for survival, compelling groups — and later families — to ensure its protection over time. They did this in part through physical coercion: building walls around settlements and fighting off would-be invaders. But they did it too by controlling the reproductive capacity of a group’s members, and the ways in which they shared, ceded, and ultimately bequeathed their wealth.

In other words, in pursuit of economic survival, early agricultural civilizations needed to control how their inhabitants produced children and how those children then inherited their parents’ land. At a time when wealth was linked primarily to land, and land secured through still-emerging systems of property rights, marriage was the contract that provided security — not only for the bride and groom, but for their children, their families, and the broader community of which they were a part.

To be sure, our ancestors had probably been falling in love for a very long time. But romantic love, historians surmise, was not necessarily a part of the marriage exchange. Instead, the early norms of marriage emerged as part of what was essentially a real estate transaction, a way for families to secure land and labor at a time when both were scarce and crucial to their survival.

This was the fundamental equation that continued to define and shape marriage for thousands of years, though with variation across time, place, and culture.

During both the Greek and Roman eras, for instance, governments used marriage as a way of maintaining social order and producing children to become soldiers for the state. In Sparta, all men and women were legally obligated to marry and produce children; in Rome, state privileges were bestowed upon couples with more than three children. During the Middle Ages and into the early modern era, marriage became an organizing structure of the church, a way of preserving Christian morals and passing them on to the next generation. Couples married within their faith, in a church, with the blessing of a priest or other clergy member. Socially, marriage still provided a source of stability and a pool of legitimate heirs. Individually, it provided sex along with a basic economic bargain: poor people married to muster their resources, rich ones to preserve and extend their fortunes. Romance, if it happened, was not really the point.

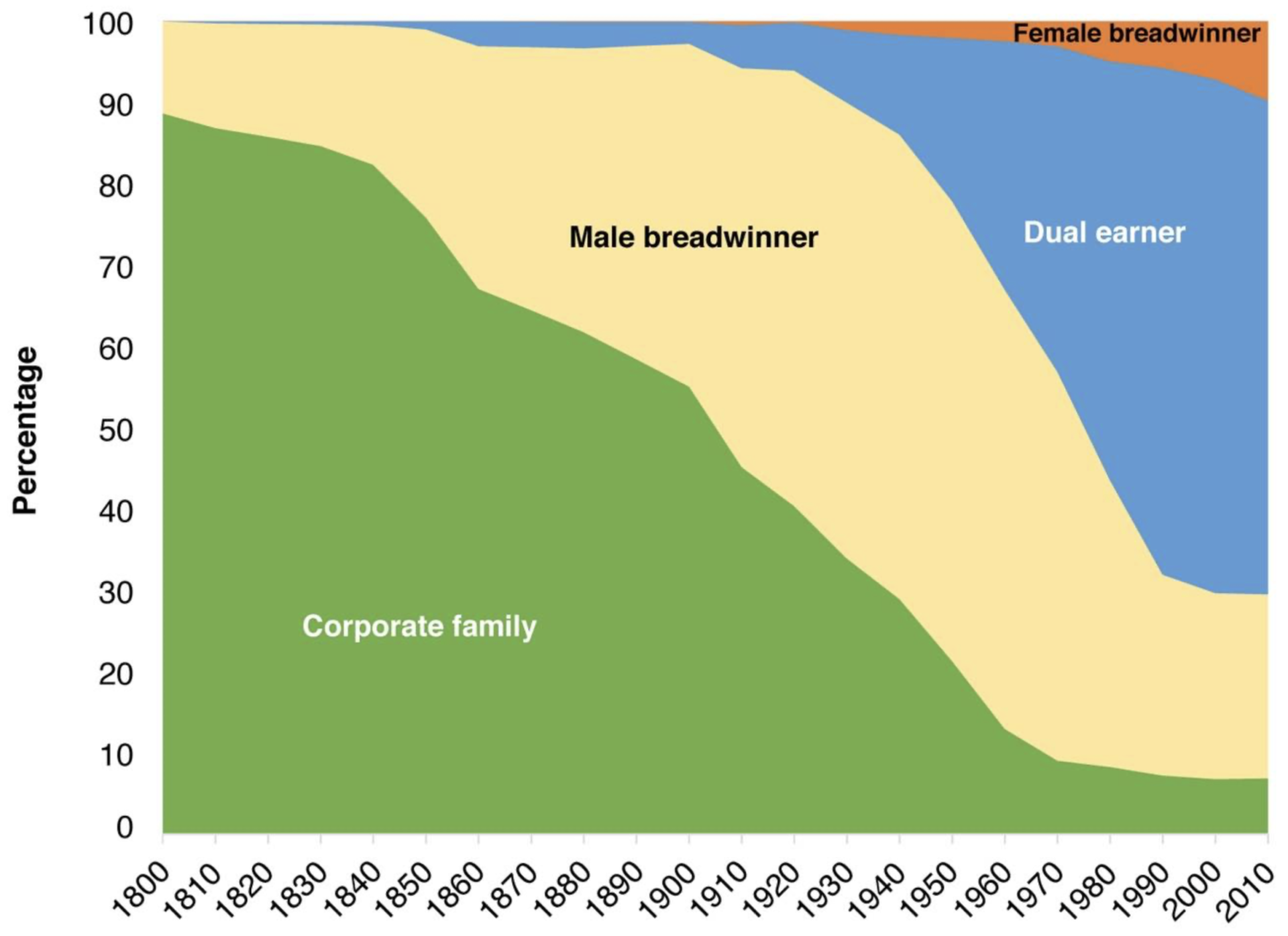

Matters started to change during the Industrial Revolution, when dramatic shifts in the means of production swept across the Western world. The advent of the steam engine, of railways and steamships and power looms, brought changes to nearly every aspect of society, from the jobs people held to the places and social structures in which they lived. Marriage was no exception. As the growth of the manufacturing economy pulled generations of agricultural laborers off the fields and onto factory floors, the extended families that had long prevailed across Europe were gradually replaced by what we now consider nuclear families. Family sizes began to shrink, and men who had once worked side by side with their wives and children increasingly left home each day to join the growing urban labor force. Some of this shift was occasioned by changing social mores and the greater incomes that industrialization eventually provided even to the working class. But much, too, was a direct result of the specific technologies of this age: heavier machinery prized higher levels of upper body strength, giving men a general advantage in the factory and relegating women to more domestic spheres.

Meanwhile, the expansion of industrial technologies also reshaped long-standing geographic and demographic patterns. In previous generations, young people tended to stay in the towns or villages where they had been born, and to settle into their parents’ and grandparents’ occupations. But as economies shifted away from their rural roots, young men and women began to migrate toward bigger cities and find partners on their own, rather than relying upon the family connections and matchmakers of yore. In the process, love — or at least romantic affection — entered the marriage equation for the first sustained time. Young people tended to wait until they had attained at least some measure of economic security, and then built a family with a partner of their choice. Far from their birth families, and without either the demands or sustenance of an agricultural lifestyle, they fell into the patterns of labor that we now take almost for granted: the husband went to work for a monetary wage, while the wife assumed the unpaid work of a single-family household.

As this social transition unfolded, the transaction of marriage shifted accordingly. Increasingly, and then overwhelmingly across the Western world, marriage became a contract between husband and wife, rather than between the would-be husband and his bride’s family. It rarely included any kind of dowry or bride price. Instead, the contract captured an individual exchange, partly explicit and partly implicit: the man promised “to love and to cherish” and provide economic support; the woman, to love and cherish in return, and to provide the family’s housework and child care. Men became their families’ anchors to the outside, hurly-burly world; women their protectors against sin, disease, and debauchery. Both partners received sex, companionship, the possibility of children, and the promise of fidelity. If eternal love wasn’t always part of the bargain, affection was, along with a more equal but still sharply differentiated set of expectations and responsibilities.

This state of marital affairs prevailed well into the twentieth century. Even amid the fights for women’s suffrage, and in households whose economic circumstances forced or encouraged women to work outside the home, the man of the household was seen as the breadwinner and his wife as the mother and homemaker. Sex outside marriage was generally frowned upon across the Western world, as were children born out of wedlock.

In 1960 and 1973, however, two events triggered what would become massive changes in the underlying bargain of marriage: the commercial release of the birth control pill and the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision to grant a right to abortion in Roe v. Wade. Together, these developments had the effect of dramatically reconfiguring what both partners expected to bring to a modern marriage, and what they expected to receive in return.

The pill has become so commonplace that it may be difficult to see just how profoundly it has changed the marriage bargain. Approved initially as a treatment for “disturbances of menstruation and pregnancy,” the pill came to market as a contraceptive in 1960. It followed in a long line of birth control methods, some more effective than others, from abstinence to the rhythm method to condoms made from sheep’s intestines. But “the pill,” as it almost instantly became known, was the first contraceptive method — the first technology — that reliably worked.

Understandably, early critics of the pill railed against its implications. Feminist observers disdained it as a dangerous product of corporate greed and a tool of patriarchal control; Pope Paul VI rejected it as an “unlawful” means of circumventing procreation. But the bigger implication of birth control was what it did to marriage, and specifically to the implicit contract that had come to define the post-industrial union. Because once women — rather than only men — had access to contraception, they were free, physically at least, to have sex without the fear of conception, and thus outside of marriage.

Before the pill, an unmarried woman who got pregnant was either shunned from society, forced to give up her baby, or under extreme pressure — from parents, religious authorities, and society at large — to get married. Men who impregnated women were similarly under pressure to marry them and become legitimate fathers to their children. But once the fear of pregnancy was reduced on both sides, and once abortion became a legal alternative to carrying an unplanned pregnancy, the severed link between sex and pregnancy also rapidly severed the link between sex and marriage. Suddenly women could have sex as they desired, with whom they desired, without necessarily waiting for that ring on their finger. And men, less obviously but perhaps more powerfully, were free to have sex with women and even impregnate them without assuming the responsibility of entering into marriage or parenthood.

These shifts were almost certainly not the intended result of the pill. Indeed, many of its earliest advocates, such as Margaret Sanger, were primarily devoted to preventing poor families from having more children than they could reasonably support. And Katharine McCormick, the heiress who almost single-handedly funded the science that went into the pill, was driven by a deep-seated and personal desire to protect married women against the possibility of transmitting devastating genetic mutations to their future offspring. For them, and presumably even for the scientists and executives who brought the pill to market, contraception was a tool for protecting couples and marriages, not undermining them. And yet the social math of their invention proved undeniable: once the risks of extramarital sex were reduced, marriage rates began to fall in the United States, while the incidence of pre- and extramarital sex rose proportionately.

Indeed, as George Akerlof, Janet Yellen, and Michael Katz showed in a 1996 paper, the widespread availability of the pill and abortion led to a skyrocketing of out-of-wedlock births, or what the authors called a “reproductive technology shock”: “Although many observers expected liberalized abortion and contraception to lead to fewer out-of-wedlock births, in fact the opposite happened because of the erosion in the custom of ‘shotgun marriages.’”

The technological tools, then, of contraception and abortion had changed the calculus of sex and marriage. Sex became cheaper — that is, it came without the accompanying cost of marriage. And the opportunity cost of marriage had risen, since it meant giving up the additional sex one could find outside of marital constraints. Between 1960 and 2022, as U.S. marriage rates fell from 8.5 per thousand people to 6.2, the share of births out of wedlock rose from 5 percent to almost 40.

Meanwhile, by the 1990s, the widespread effects of contraception and abortion on marriage were being accelerated by the development of technologies for assisted reproduction. Like the pill, these technologies — such as artificial insemination, in vitro fertilization, and egg freezing — were initially intended to strengthen traditional norms of marriage. Artificial insemination, for instance, was first used almost exclusively by married couples who suffered from infertility and were desperate to conceive children. So were early uses of in vitro fertilization, egg donation, and pre-implantation genetic diagnosis: all were deployed primarily by married heterosexual couples who turned to science when sex alone failed.

Over time, however, these technologies began to seep into, and then shift, the form of the family itself. Lesbian couples turned to sperm banks, instead of men, as the source for the genetic material they needed to conceive children outside of marriage; so, too, did single women who wanted children but either had not found, or did not want, a husband.

In this regard, contraception and abortion had paved the way for the changes subsequently wrought by assisted reproduction. Because once both sex and conception were split from marriage, marriage was liberated, or left, to evolve in new ways as well. If people didn’t need the sanctity of marriage to produce children, and if those children could even be produced without the direct participation of another parent, individuals could marry across a whole new spectrum of possibilities. Which they promptly did: between 2015, when the U.S. Supreme Court legalized same-sex marriage, and 2020, nearly 300,000 same-sex couples in the United States chose to tie the knot.

One could even argue that the legalization of same-sex marriage was accelerated by the use of assisted reproductive technologies, since the decision in Obergefell v. Hodges was largely based on the Court’s concern for the children of same-sex couples — children who, in many instances, had been conceived with some form of technological intervention.

Even before the advent of the Internet and the digital revolution, then, the technologies of contraception and assisted reproduction had changed the contours of marriage, shifting the terms of the existing bargain and unbundling the long-standing package of sex plus children and support.

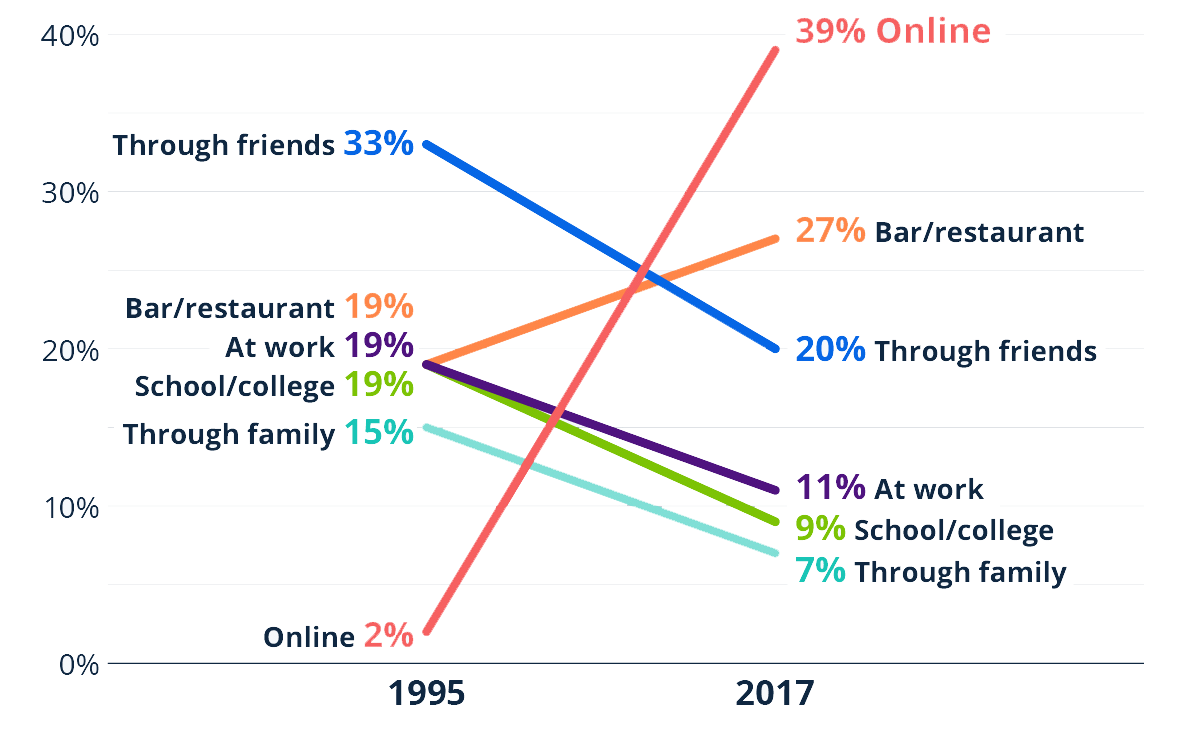

And then came Tinder and a bevy of other apps for dating, mating, and just plain sex. Grindr, Match, Hinge, Bumble — they all promised an infinity of well-curated choices, pre-configured to give you who you wanted, when you wanted, and wherever you happened to be. And to a large extent they did: between 1995 and 2017, the share of heterosexual couples who met online surged from 2 percent to nearly 40. Young people who had once relied on a church social or freshman English class to proffer up a date turned now to their phones instead. So did many older people, who found themselves alone later in life, realizing — to their dismay, confusion, or occasionally even delight — that the norms they had mastered or at least muddled through in their youth no longer applied.

It’s easy to malign the apps, or for happily married people of a certain age to rue and regret all they have done to younger generations. But the truth of this moment — the sheer mechanics of the modern social ecosystem — is that many young people rely on digital systems, rather than human ones, to shape and intermediate their most personal connections. They find friends online. They find companionship there too. And the nature of these interactions has affected, again, not only the patterns of youthful relationships, but the broader landscape of marriage and family as well, making today’s marital compact a rather novel arrangement: more complicated in many ways than its predecessors, more ambiguous, and — according to a growing chorus of political observers — desperately in need of revision.

To begin with, apps that seek to match individuals, especially those for casual sexual encounters, have accelerated the separation of sex and marriage that began with contraception. Even for those who don’t use these apps, their prevalence has shifted the expectations and values of the broader social system. Sex becomes cheaper: in basic economic terms, the supply goes up and the price any individual can expect to pay in time and effort to find a partner goes down. Because the pool of potential partners also expands dramatically beyond the social and geographical communities of earlier eras, choice becomes more varied and selective for some participants and less so for others. Specifically, because the apps highlight certain characteristics of each individual’s profile, and because potential matches inevitably use these characteristics to evaluate whether to swipe left or right, some people are just regularly judged more attractive than others. Younger women fare better than older ones on dating apps; so do wealthier and more highly educated men. Men of all races generally prefer Asian women — except Asian men, who prefer Latino women. Asian, Latino, and white women prefer white men. And many users eventually become exhausted by the plethora of choice, the endless scroll of potential partners, each in theory better than the one before.

Currently, much of the scrutiny of online dating focuses on the quality and longevity of the matches it produces, with some research suggesting that couples who marry after having met online may fare better than those who met offline, and other research suggesting the opposite. Either way, these studies overlook what may be a considerably more important effect: the fate of marriage itself. Because as the search for social partners moves increasingly online and the fatigue of these searches becomes more pervasive, many would-be partners, it seems, are simply giving up. They are traveling or getting pets instead, turning to friends rather than mates or lovers for companionship. Instead of seeing marriage as the goal it once was, many people are now painting marriage as one choice among many, as an option rather than the default.

It’s hard to blame the dating apps directly for this development, since the apps, after all, are explicitly about finding partners. But the ubiquitous sense they have introduced — that dating and mating occur in a marketplace of vast and refillable options — seems to have undermined much of what was once a more intimate exchange. Because if women don’t need men to have babies or financial security anymore, and men don’t need marriage to have sex, then much of the value of marriage — in the cold economic sense — is gone. And if what remains — love, affection, romance, and commitment — has been thrust into the market and reconfigured as a game, then participants can look elsewhere to meet their emotional needs.

Which brings us back to Mr. Kondo and his doll. To be sure, his is an extreme case. Few people fall in love with a digital creation; fewer still go through the exercise (some might say charade) of marrying one. But milder versions of this behavior are rapidly becoming more commonplace. Dozens of firms around the world now offer various kinds of technological companions for sale. Many of these are simple models — like Paro, a fluffy robotic seal frequently used as a companion for elderly patients; or Aibo, a robotic dog that responds to a handful of basic commands. Others are far more complex, using AI technologies to create at least a reasonable facsimile of human interaction. In China, tens of millions of users seek online companionship and emotional support from a growing cadre of virtual humanoid beings launched by the country’s giant Baidu corporation and others. In the United States and elsewhere, Replika AI, which offers to “create your personal AI friend,” also has tens of millions of users.

Unlike Paro and Aibo, the “Replikas” have no physical form — you can’t sit at the kitchen table with one or stroke its hair. Instead, users communicate with their Replikas in the same way we all frequently communicate with our human friends and colleagues: by typing on a screen and waiting for a reply. Of course, it’s an algorithm on the other end rather than a flesh-and-blood being, a program that is drawing its responses from a large language model rather than felt experience. But the early data on Replika suggests that its users value their interaction nevertheless. “She helped nurture my heart,” said one user, “and helped me heal when nobody else did a single thing.” When the company tweaked its algorithm in 2023, fearing that some of the relationships on the platform had become overly sexualized, users launched a revolt online, grieving over companions they had loved and now lost.

It’s too early to tell whether and how Replika-like companions will move into the cultural mainstream, much less if they will ever dislodge, or even dent, more fully human relationships at a significant scale. But the experience of using them will only improve as AI systems become more powerful, and they will presumably feel increasingly normal to generations raised on screens and immersed in digital interactions. All of which will eventually leave its mark on marriage as well: if the pill removed sex from the pact of marriage, and assisted reproduction removed babies, then digital companions raise the prospect of removing companionship as well.

Seen against the long sweep of history, it’s not surprising that marriage is now morphing from what we once knew it to be. It has done that before and will no doubt do so again. What’s different now are the pace and breadth of the disruption, coming in ever-faster waves and engulfing ever-broader swathes of people. It’s difficult to predict exactly how these changes will eventually fall and settle. In the short term, though, several patterns are likely to prevail.

First, overall rates of marriage are almost certain to continue to decline, particularly among those segments of society for whom its traditional values — sex, children, financial security — are either less attractive or more readily available through other channels. Second, individuals and communities that treasure these values may well double down on them, signaling and underscoring their preferences through commitments such as pre-marital purity pledges or “trad wife” marriages.

But most significantly, and perhaps most ironically, as technology sweeps across our social and sexual lives, marriage may actually become more and more about love. Because when all the other elements of marriage’s historical contract have been stripped away, what remains is its most ephemeral and priceless piece. Will some people turn away from marriage if they can’t find the right person with whom to share their love? Absolutely, because now they can. Will others leave a marriage if the relationship becomes unsatisfying or unhealthy? Yes.

Yet the fact that, for most people, marriage has become an option rather than an expectation could also strengthen the institution for those who choose to embrace it. Because once marriage is ripped from the exchange of family commitments and property that initially sat at its foundation, once it is no longer necessary to ensure the legitimacy of children or the financial security of young women, marriage is left, sort of, with love. It is a commitment, plain and simple, to spend one’s life with one other person — to share possessions and pain, dirty laundry and family meals, to grow happy, or grumpy, and old together, to resist the temptation of other paths and people in favor of just one.

Shorn of the requirements it once entailed, what remains in marriage, and what is being exchanged, is love — love for the long term, love intertwined with desire, love that has no greater use than its own existence. It is an ephemeral bargain, of course, one that has moved beyond the realm of material goods to occupy a more intimate and sacred space. But as technology claims an ever-greater share of our lives, these sacred connections may become increasingly vital — priceless goods to preserve, cherish, and protect, for as long as we all shall be.

Keep reading our Summer 2025 issue

Uncle Sam’s dream house • What toasts your bagel • Tech & marriage • Subscribe

Aryanna Garber is a research associate at Harvard Business School.

Exhausted by science and tech debates that go nowhere?