It’s pretty simple. People want children who look like them, who will be healthy and succeed in life,” said Lillian Tara, a master’s student at Harvard University who offers fertility education to young women. More specifically, many people want children with Ivy League genetics, and they’ll pay tens of thousands of dollars for eggs from a woman who has the credentials.

The use of in vitro fertilization has grown dramatically in the United States since the first American child was born by this method in 1981. Heterosexual couples experiencing infertility, same-sex couples, and even single adults increasingly use IVF to have children. As the technology and its odds of live birth have improved, IVF has become ever more attractive. In 2021, about 240,000 people in the United States used assisted reproductive technology, chiefly IVF, which resulted in 97,000 live-born infants, roughly 2 percent of all births.

But the technology isn’t merely helping people have children. The IVF industry is promising to help parents have a specific type of child, especially if they use donated genetic material.

Finding the right donor is “a deeply personal process,” said Tara, and parents “often want to connect with the donor because they imagine their future child in those interactions.”

This is the perspective that fertility agencies have embraced. Agencies reassure applicants that donating eggs is “the ultimate act of service” and could be “one of the most rewarding decisions of your life.” “It’s pretty profoundly altruistic,” Tara said. “Saying ‘it helps people’ sounds cliché, but these couples are usually infertile and often grieving. Being that person to help them start a family is huge.”

But there is another side of the story that’s obscured by this language. What advocates describe as matching with the right donor is also shopping. Many couples won’t accept eggs from just any woman; they will pay handsomely for eggs from a woman who attended a coveted university. And what’s called “donating” is really selling. Many egg donors feel they are giving a beautiful gift to heartbroken couples, but as Tara admitted, “for the young women just starting out their careers, the money doesn’t hurt.”

IVF as practiced today abounds in strange tensions like these — between offering precious gifts and satisfying personal demands, emphasizing altruistic “donations” and debating prices, exercising control and surrendering to chance. “When going through infertility and the exhaustive IVF process, the only real solace is that you have freedom to choose a donor that has some of the traits you value in yourself,” Tara said. “And with the information on prospective donors laid out, the impulse is, ‘well, now that I have some say, I might as well take advantage of it.’”

When given the choice, intelligence seems to be what people want in their children more than any other trait besides health. Rite Options, a fertility agency with offices in Philadelphia and Garden City, New York, is blunt about this. “Most intended parents have the image of an ideal egg donor in mind. She is likely someone who is attending or has graduated from an Ivy League school and is accomplished in many extra-curricular activities,” says the agency’s website. “Rite Options makes finding Ivy League educated, intelligent egg donors a number one priority!”

Elite Donor Solutions, another agency, affirms that hopeful parents seek an Ivy League donor with a “strong academic background” because they “want the best possible chance of success for their future child.” It adds that “many intended parents are drawn to these donors because of the prestige associated with having a degree from one of these universities.”

“People are blinded by prestige,” Lillian Tara told me. “The Ivy League brand works in the egg donation market the same way it does in the job market. It’s a basic signal of being capable and well-adjusted.” “It’s a status that they’re hoping will actually translate to their child,” Jennifer Lahl, founder of The Center for Bioethics and Culture Network, told me. “But there’s no guarantee that because the egg donor was smart that the child will be.”

The demand for an Ivy League egg donor is high, but the supply is sparse, so fertility clinics can charge massive premiums. Intelligent, attractive, healthy, successful women have no obvious limit to their value on the egg marketplace.

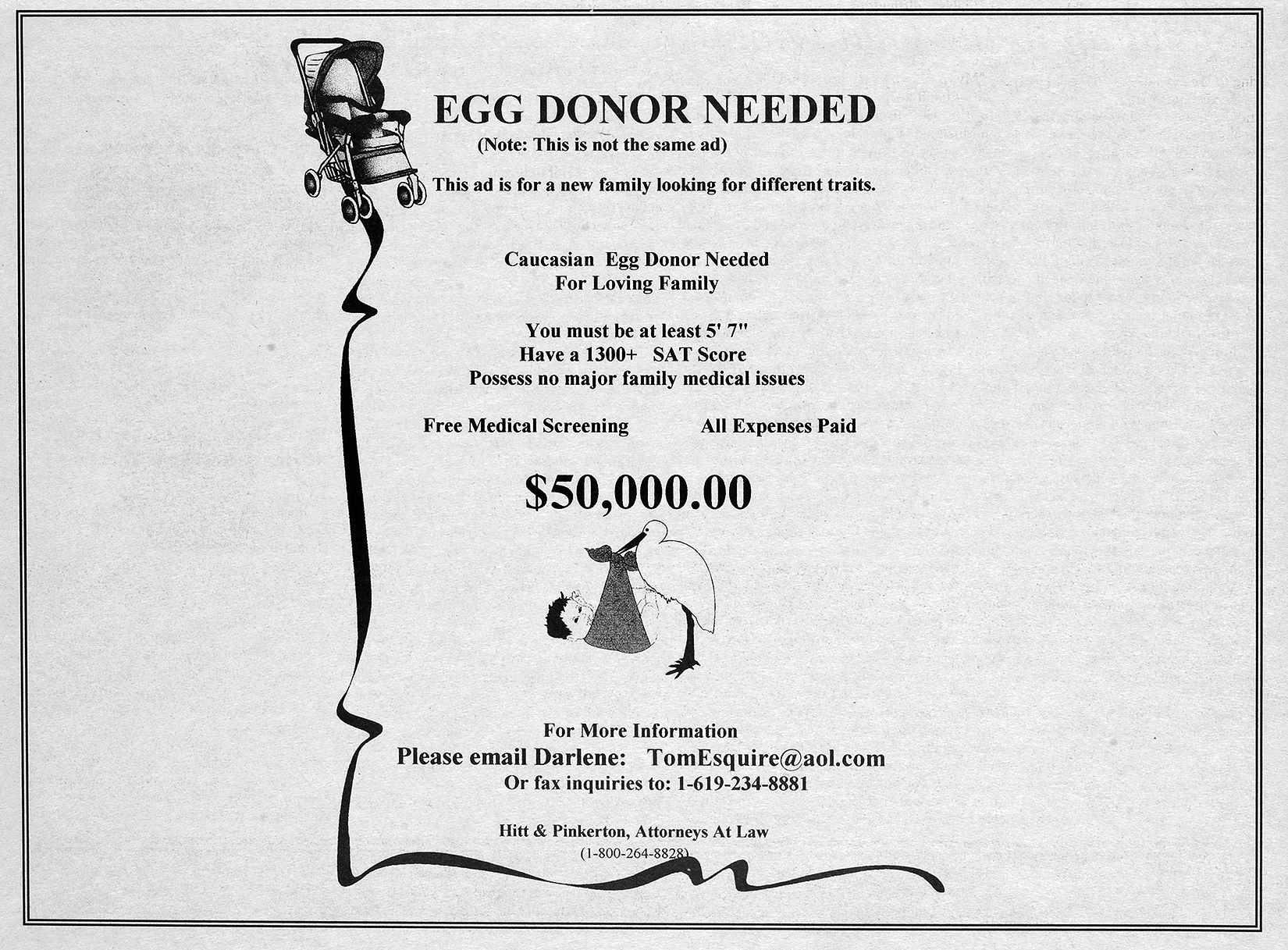

Eligible women can earn $5,000 to $10,000 from a single egg donation cycle, with all medical and travel expenses covered. But much larger amounts are offered to women with impressive degrees. The agencies Ivy Surrogacy and Elite Donor Solutions advertise that Ivy League women can earn up to $50,000.

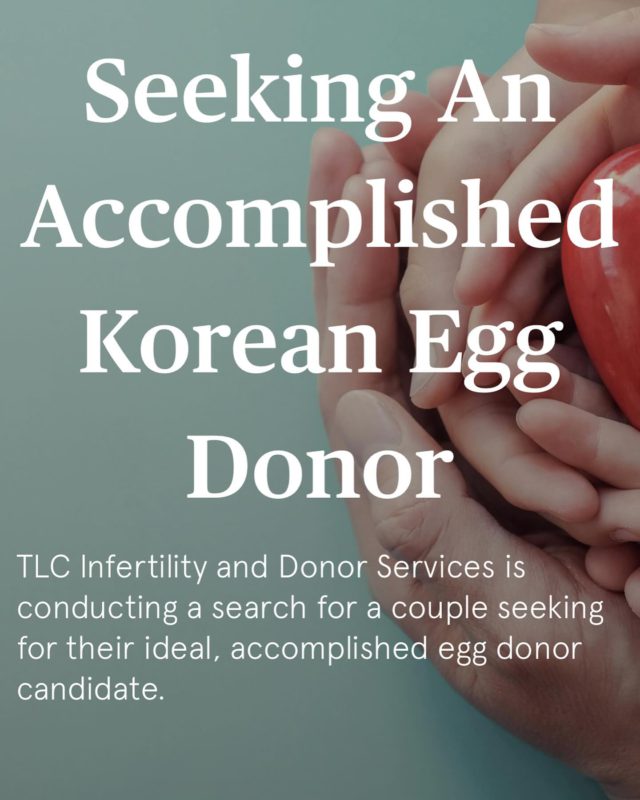

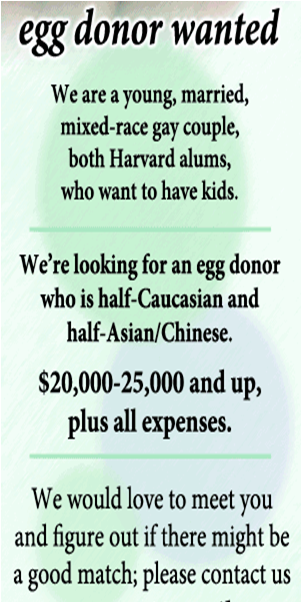

Fertility clinics and intended parents have also long been recruiting women from prestigious universities through direct advertising. A 1999 ad in the Harvard student paper offered $50,000 to “intelligent, athletic” women with SAT scores of 1400 or above. At Yale in 2008, an ad offered $100,000 to a “very attractive” Caucasian. Sometimes students receive targeted emails: at M.I.T. in 2021, female students with last names like Wu, Huang, or Chen received an email from an individual offering $50,000 for a Chinese egg donor who is “top in her class” with “several awards in high school and university.”

“It certainly was a lot of money, and that catches your attention,” the writer Leah Libresco Sargeant told me on the phone, as she reflected on advertisements for egg donation she saw in campus publications while she was an undergraduate at Yale from 2007 to 2011. “I had the right degree for some of the offers, but I wasn’t always tall enough for others, or athletic enough. In some cases, I was the right ethnicity.”

Digital tools have made egg selection easier for hopeful parents looking for a woman with specific physical or genetic traits, in addition to education status. Tulip and similar databases are like Tinder but for finding an egg donor, with filters for desirable traits like eye color, hair color, height, and SAT score. Donor Concierge will help you discover Jewish egg donors, who are “some of the hardest to find.”

British couple and reality television stars Ollie and Gareth Locke-Locke recall in a recent interview that they had “probably spent quarter of a million quid” (just upwards of $300,000) on IVF services. Ollie says of the egg donor they were looking for, “I wanted them to be super fit,” adding “I wanted to find someone that I know is going to be an absolute smoke show.” Gareth describes a Los Angeles fertility company that “basically is supermodels who are Ivy League educated” — the couple selected a donor with Columbia University credentials. “It’s a bit prostituty, isn’t it?” Gareth asks. Ollie responds, “I think it’s quite fabulous, but the eggs were terribly expensive, but we got the Brazilian supermodel.” The couple used a different woman as the surrogate and now has twins.

I wondered how much money I could make: I’m a Princeton graduate and current Oxford student, though neither “super fit” nor a “supermodel.” So I asked.

“The majority of my clientele are from Northern California and Southern California — Beverly Hills, San Francisco,” a woman, who runs a company that pairs couples with donors, told me over the phone. “I even have plenty of clients coming from other countries that are looking for donors with your education and are willing to pay certain amounts.” She guessed I could make up to about $25,000 for my first egg donation.

She explained the process: I would fill out a profile online, hopefully match with a couple, take hormonal birth control for a time, take injections, travel to the couple’s clinic, then finally undergo the egg retrieval procedure. The whole thing would span from a few months to about a year.

I’d be paid in stages throughout the process, with the final installment at the end, even if my eggs aren’t successfully fertilized or implanted. And the recovery is supposedly “not terrible,” although “it’s different for everyone,” the woman explained. If my eggs are successful, I could undergo the process again and earn greater compensation. The guidelines of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine limit a woman to six egg donation cycles in a lifetime, although one can exceed that, as some women have, presumably by lying.

I was curious: could I qualify as an “exceptional” egg donor? I wanted to learn what the fertility clinics were looking for, so I began an online form.

The application is eerily pageant-like, and I almost expected a numerical score after completing all the questions, which took about two hours. The agency wanted to know virtually everything about me — and my entire family. Skin type? Dry. Have you ever had braces on your teeth? Yes, when I was eleven. Freckles? Not really. Predominant hand? Right. Musical talents? None, unfortunately. What was your personality like as a teenager? Well, I didn’t really have one, since I just did ballet and schoolwork. Do you drink coffee? Yes, like all college students.

The questions are oddly specific, even invasive. Did you have white hair at a young age? Nope. What was your ACT score? A perfect thirty-six. Have you had sex in exchange for money or drugs in the past 5 years? Absolutely not. Have you ever been injected with bovine (beef) insulin? No, I didn’t even know that existed. What is your maternal grandfather’s blood type? I have no idea, and he’s dead now, so I can’t ask. How did he die? Vasculitis. Do you have vasculitis? No, I don’t think so.

I felt disturbed to be so vulnerable. My own boyfriend doesn’t know all this about me — not because I am unwilling to share, but because it isn’t important. Could I really give all this information to strangers on the Internet so they could evaluate me and compare me to other women? And what would it mean if they rejected me?

Just as prospective parents pick and choose women to find ideal eggs, scientists pick and choose embryos in the lab to sort better from worse.

Penn Medicine’s Fertility Blog explains that, after eggs are surgically retrieved, sperm are filtered “to find the healthiest ones,” and then insemination combines “the best sperm with your best eggs.” Multiple eggs are fertilized for better odds, since only about half of the fertilized eggs will develop to the blastocyst stage, and about half of all transferred embryos in the United States result in live births. Determining which embryos deserve implantation — and a chance at being carried to term — involves comparing their genetics. Preimplantation genetic testing can detect some disorders, like sickle cell anemia and muscular dystrophy.

“The reason why a lot of IVF couples want to choose embryos is because they’re infertile in the first place, so these pregnancies can be very precarious, and so choosing embryos, one over the other, is basically a goal to try to make it work,” Max Meyer, a writer who has defended IVF, told me. Meyer was conceived via IVF and born in 2000; his parents had struggled with infertility, then bore three children through IVF using their own genetic material, and then had a fourth “surprise” child who was conceived naturally.

“What happens most of the time in regular reproduction is that the best sperm tends to reach the egg faster, and the best eggs are more likely to survive,” Meyer continued. He believes that critics of IVF, who may see it as a form of control over which embryos should succeed, ignore that scientists are merely imitating nature. “If the argument is you shouldn’t be allowed to do this treatment, but if you’re going to do it, you should do it in a way that maximizes failure, then I don’t think that that’s an honest argument.”

There are genetic tests not only for health but also for cosmetic traits. The website of the Fertility Institutes offers a service for selecting embryos based on their future eye color. It also boasts its successful “family balancing” procedures, which let couples select a child of a preferred sex.

For each child born through IVF, there are many that are never carried to term. Estimates of how many frozen embryos there are currently in the United States vary from around half a million to a million. Some will be given to infertile couples, others donated to research, or unceremoniously “disposed” — killed. Then there are the embryos that are deemed unhealthy and unsuitable for transfer after genetic testing, which are often described as “abnormal,” “poor quality,” or “incompetent,” and are thus “discarded.”

“This is a revival of the eugenics that we rightly came to feel revulsion toward,” Robert P. George, a professor at Princeton University who served on President George W. Bush’s Council on Bioethics, told me. He argued that, by “replacing the marital act with a factory process,” IVF promotes “the commodification of children, turning human beings into products, which are then necessarily, as products, subject to quality controls.”

Max Meyer disagrees, arguing that “inferior” is just “a proxy for the likelihood of this embryo to succeed in a very difficult IVF process.” He thinks that it is IVF’s critics who are guilty of morally downgrading children conceived through the technology, saying that they use phrases like “test-tube baby,” “designer baby,” “unnatural baby,” and “abomination.”

Certainly, most people pursuing IVF don’t believe they are preying on vulnerable women or engineering the human species. They just want to raise a happy, healthy family. “There are predatory parts of the egg-buying industry, and there are ways that people who are offered a huge amount of money are subject to exploitation,” Leah Libresco Sargeant said. “But there’s also a lot of real love and generosity and curiosity about how to be of service to others.”

“Eugenics” may remind us of sinister regimes that engaged in social engineering, not private family planning. But to Sargeant, the intimate decisions between fertility experts and prospective parents are especially concerning. “Once you’re giving parents that degree of choice over their child, you’re placing pressure on them.” She added, “You’re getting an opportunity that’s not a natural opportunity, that’s an opportunity we’ve engineered” — the power both to choose the children we want and the ones we don’t.

Keep reading our Spring 2024 issue

Highways vs. urbanism • The IVF problem • Depressive AI • LSD is back • Subscribe

Exhausted by science and tech debates that go nowhere?