This essay contains spoilers throughout for Piranesi (2020), Serenity (2005), The Tempest (1623), and Genesis (ca. 1400 b.c.). Consider yourself warned.

If you could either fly or be invisible, which would you choose? According to a Rorschach test immortalized by This American Life, the superpower you prefer reveals your disposition: “A person who chooses to fly has nothing to hide. A person who chooses to be invisible wants clearly to hide themselves.” It might be your own nefarious activities you wish to hide, or you might desire to be hidden from the ill intent of others. Either way, to seek hiding is to live with an awareness of the shadows that someone with the innocent confidence of flight is free to soar above.

In Susanna Clarke’s fantasy novel Piranesi, we meet an exceptionally innocent narrator who dates his life from a sublime encounter he has with an albatross. As the bird comes swooping toward him, he has a vision that they could merge into a being he knows of but has never seen — “an Angel!” — and imagines how he will fly through the world with “messages of Peace and Joy.” When he and the albatross do not become one, he instead offers it a gracious welcome, and helps it gather materials for a warm, dry nest. He sacrifices his own resources to do this, “but what is a few days of feeling cold compared to a new albatross in the World?” From this point on, his detailed notebooks refer to “the Year the Albatross came to the South-Western Halls.”

The man called Piranesi (though he correctly senses that is not really his name) is one of only two human inhabitants in what he calls the House, a labyrinth of marble halls and ocean life and statues of people and nature and legend. Piranesi’s many energies are devoted to exploring and documenting the House with care. The second person, a man he calls the Other and regards as his colleague and friend, wishes to direct their research toward discovering “a Great and Secret Knowledge hidden somewhere in the World that will grant us enormous powers.” Piranesi, who knows the House much better, repeatedly insists to him that there is no such secret.

In this he is half right: there is nothing there to be extracted for the purposes the Other has in mind. But Piranesi, a naturalist unlike any who walk the earth today, seems to already have the Knowledge in the living of it. He is at one and in love with the world he studies. His scientific disposition harks back to what Clarke has described as a premodern view of nature: “Ancient peoples did not feel alienated from their surroundings the way in which we sometimes do. They did not see the world as meaningless; they saw it as a great and sacred drama in which they took part.” The Other is disenchanted from this outlook; though he is not himself invisible, the splendors of his surroundings are invisible to him. Piranesi compares him to a statue of a man kneeling among the broken pieces of a sword and sphere:

The man has used his sword to shatter the sphere because he wanted to understand it, but now he finds that he has destroyed both sphere and sword. This puzzles him, but at the same time part of him refuses to accept that the sphere is broken and worthless. He has picked up some of the fragments and stares at them intently in the hope that they will eventually bring him new knowledge.

The knowledge Piranesi most longs for is of other people. He believes that, aside from the two living humans, there are only thirteen others who have ever existed, based on the number of skeletons he has found, and he lovingly tends to their bones as his “religious practices.” He gives them names, speculates about their histories, and routinely visits them to report on his doings and “describe any Wonders that I have seen in the House. In this way they know that they are not alone.” But he has a hunch that, in some far-off halls, there may be at least one or two more living inhabitants, and is desperately curious to meet them.

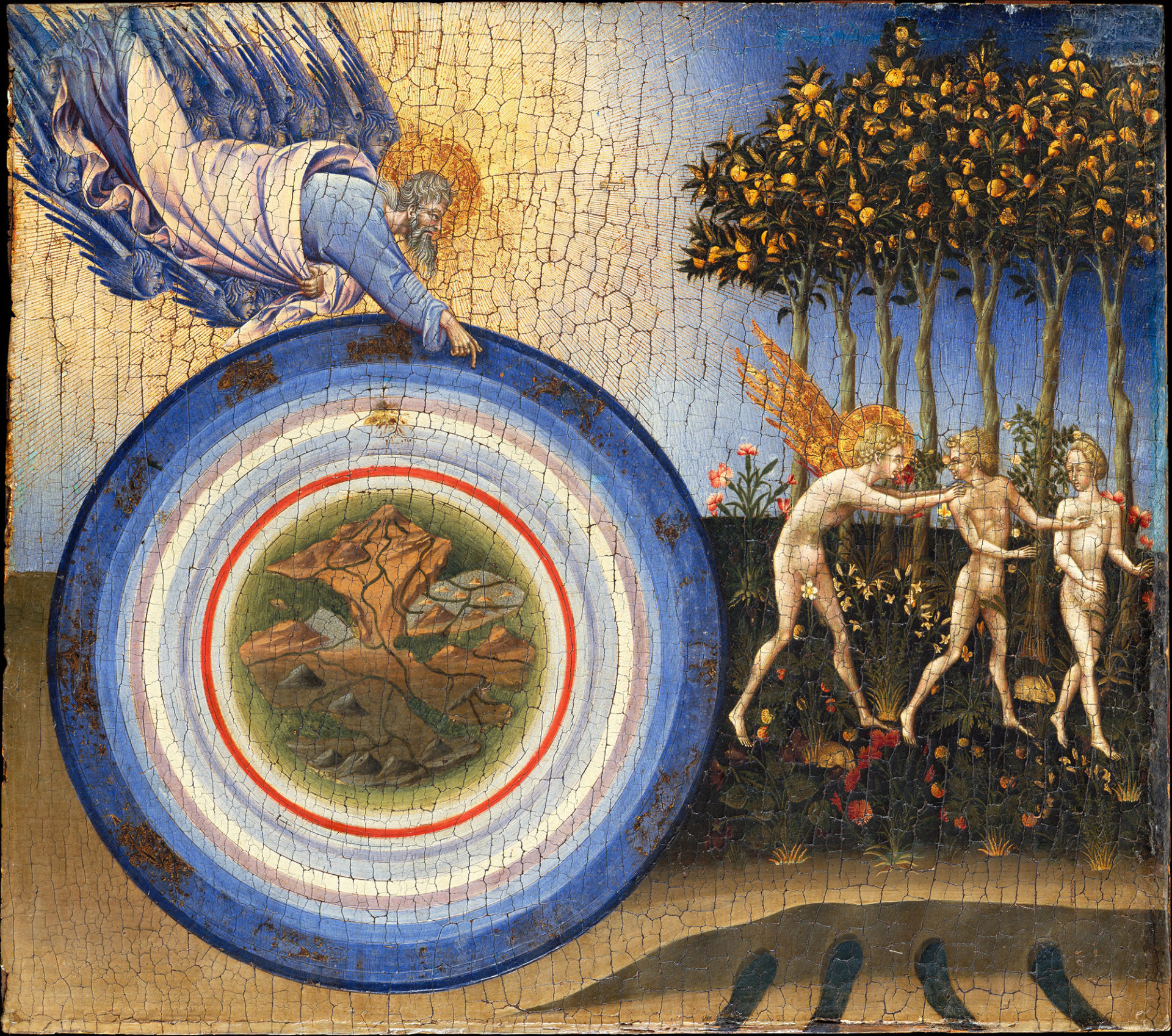

One day, a third person does appear, and offers Piranesi this explanation of his home: “Once, men and women were able to turn themselves into eagles and fly immense distances. They communed with rivers and mountains and received wisdom from them. They felt the turning of the stars inside their own minds,” an energy that has flowed out of the modern world. “But it seemed to me that the wisdom of the ancients could not have simply vanished. Nothing simply vanishes. It’s not actually possible.” The House, indicates the mysterious visitor, whom Piranesi names the Prophet, is where such ideas and energies go instead of disappearing.

Notwithstanding his affirmation of Piranesi’s vision of a person with wings, much about the Prophet is vaguely menacing — not least that he casts doubt on the character of the Other, whom till now, despite their disagreements, Piranesi has trusted implicitly. One of them must be lying, and he has never known anyone to lie. In his uncertainty, he too begins to lie and hide — first concealing some of his thoughts and research into the truth of things, which had been perfectly transparent, and later hiding himself from human encounters he had once eagerly desired. To know the shadows is to seek invisibility within them.

What will happen to our Piranesi when he learns how dark the truth really is? Will his disillusionment in other people precipitate another disenchantment of the world?

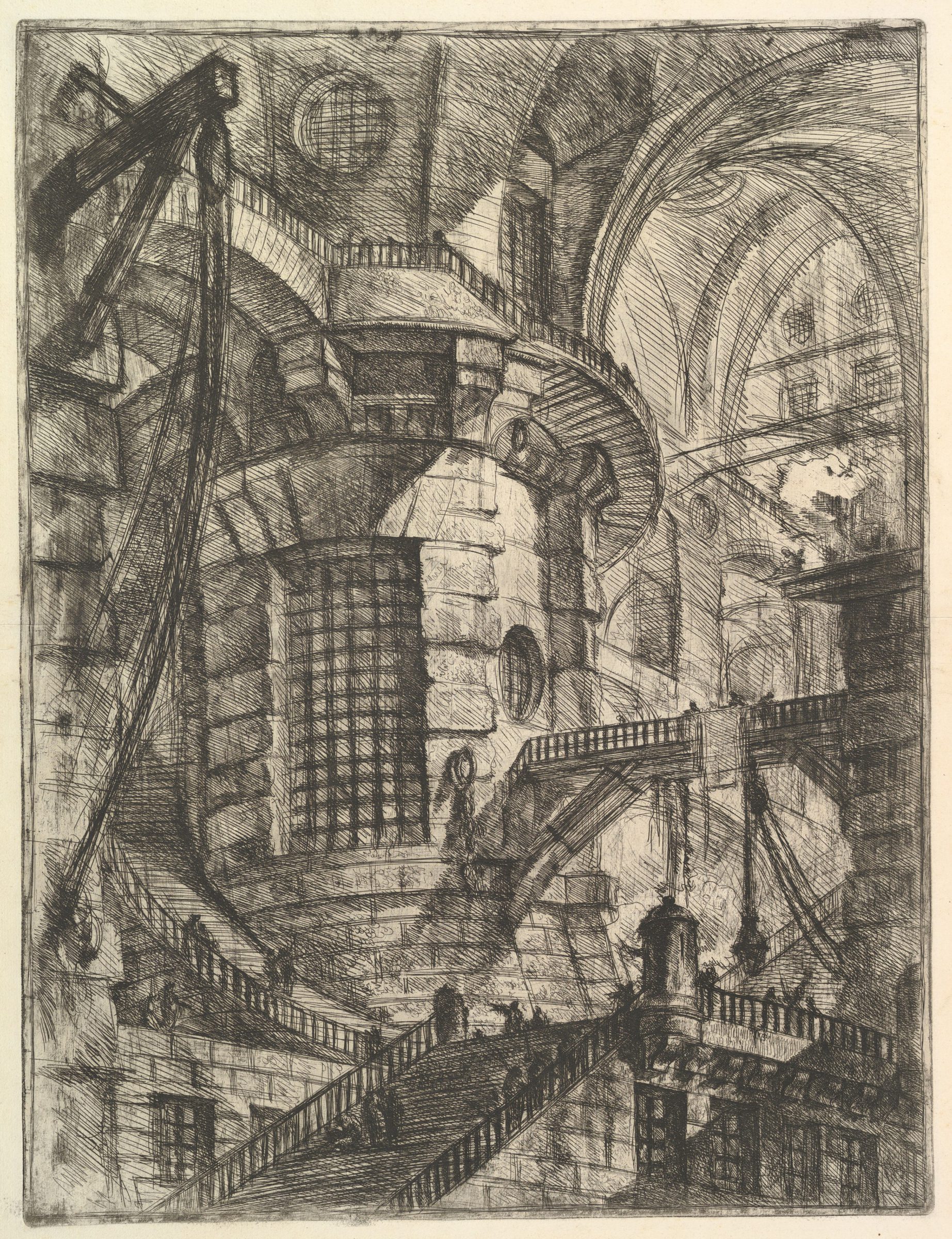

The truth is this: Years ago, in modern-day London, the Other (Val Ketterley) was a student of the Prophet (Laurence Arnes-Sayles), an anthropologist who discovered a pathway to the alt-world of the House and led several people there to their deaths. Ketterley, wishing to learn more about the House’s unusual properties without getting lost in it himself, entrapped a young writer named Matthew Rose Sorensen into going there with him. The House has such a powerfully amnesic influence that Sorensen soon forgot everything about his old life, his family, even who he is. Ketterley, who would go back and forth between one world and the other to check on this nameless person and his research, named him after an Italian artist famous for his etchings of fantastical prisons: Piranesi.

Piranesi finds this history documented in a hidden section of one of his old notebooks. Outraged by the betrayal, he is immersed in “long, sick fantasies of revenge,” imagining himself killing the Other in any number of ways until his anger is finally spent. Meanwhile, a different wave is building. Piranesi has calculated that the tides will bring a great flood through the House on a certain day. The Other takes the opportunity to lay a trap for someone else from the outside world, a police officer named Sarah Raphael who has been looking for Matthew Rose Sorensen, luring her back just in time for the flood in hopes that she will die and keep his secret safe. Instead, it is the Other who drowns. When it comes to the point, despite Piranesi’s newfound knowledge and a threat on his own life, he is moved to see the Other in danger and makes every effort to save him.

“O, the cry did knock against my very heart! Poor souls, they perished,” laments a person very much like Piranesi on witnessing a tempest toss her enemies at sea. This person is Miranda, daughter of Prospero, who long ago spirited her off to a magical island away from the treacherous real world. Like Piranesi, it was “foul play” that made them come, but it was restorative to be there. Except they cannot stay. After a time, a storm comes (also engineered by Prospero) to set right that foul play and ultimately send them home.

Like Piranesi, the now-grown Miranda knows nothing of society. Nearly as deprived of human contact as he has been, she is just as keenly fascinated by others of her kind. When she walks out in the last act onto a beach containing the dregs of humanity, people the audience has observed to be traitors and buffoons, she exclaims, “O, wonder! How many goodly creatures are there here! How beauteous mankind is! O brave new world, that has such people in it!”

This is a laugh line, the distance between impression and reality so great that the “brave new world” has become an ironic catchphrase for dystopias from Aldous Huxley onward. And yet, deep down, perhaps it is Miranda with her purity of heart who sees the truth of things more clearly: that another person is indeed a wonder. That even the worst of them are valued. That life with them is worth the cost.

Both Miranda and Piranesi are the gracious way they are from having no concept of what that cost might be. But once they learn, the grace remains. This turns out to be Piranesi’s approach to the Other, even knowing who he is and what he’s done. After the flood subsides, Piranesi gathers up his body and “comforts” him, promising to “put you in good order and you can rest in the Sunlight and the Starlight. The Statues will look down on you with Blessing. I am sorry that I was angry with you. Forgive me.”

He requests forgiveness of the one who should be asking it of him, though there is little reason to believe this would have ever happened. Piranesi confronts the House for allowing the Other to die, though it seems a mercy that it did. The Other did not display one redeeming quality in his entire life, lacking even the intelligence of the depraved Prophet. But Piranesi includes him in the human community with the same reverence given to all in death. In his heart, Piranesi makes room for the dismal truth he now knows without erasing the lived truth he felt before; as he drifts off to sleep, the last living person in his world, his thoughts turn to the Other: “He is dead. My only friend. My only enemy.”

The audiobook of Piranesi is masterfully narrated by Chiwetel Ejiofor, who is best known for his award-winning performance in 12 Years a Slave (2013), but whom I know first and foremost for his role as the Operative in the 2005 space opera Serenity. The coda to Joss Whedon’s (dastardly) short-lived 2002 show Firefly, Serenity depicts a universe under the incomplete control of the Alliance, a singular unified government whose benevolent intentions are to prevent all conflict, large and small. Naturally, the enforcement of this control is not benevolent — but as the Operative, one of the enforcers, understands it, harsh measures now are in service of a perfect vision to come in which they will not be needed. The whole universe would be the magical realm where fallenness is solved. He is a deep believer in this vision even with the recognition that someone like him will have no place in such a world. In his selflessness, he doesn’t even have a name; he is simply the Operative.

The crew aboard Serenity are among the wrinkles in this vision the Alliance needs to iron out, flying around out of reach, answering to no one but their own captain, Mal, and stumbling into state secrets that could blow the whole experiment apart. The Operative is sent to track them down. Meanwhile, they wind up on a hidden planet named Miranda, meant to be a brave new world, where something has gone terribly wrong. It turns out the Alliance had been pumping “Pax” into the air to reduce aggression in the population, which instead made people so tranquil that they lost the will to do anything at all, and just lay down and died. It is like Charn, the dying world from The Magician’s Nephew that inspired Susanna Clarke, whose eerie calm buries the tragedies of the past under a numbing emptiness.

Mal determines that this effort to “make people better” has to be exposed. At great loss, he manages to get a video of evidence into a broadcast center, just as the Operative catches up to him. “Do you know what your sin is, Mal?” he asks as they tussle. “Hell, I’m a fan of all seven,” Mal retorts, in keeping with his name. He wins the duel, and instead of killing off the Operative as the moment seems to call for, Mal announces, “I’m going to grant your greatest wish: I’m going to show you a world without sin.” He rolls tape of a place so pacified that there is no one left to do each other harm.

Swashbuckling aside, Mal is not really interested in sin for its own sake, but rather as a byproduct of freedom. (Between flight and invisibility, Mal “You Can’t Take the Sky from Me” Reynolds would choose to fly.) Piranesi early on remarks that the Other complains of bird droppings and cannot see them for what they are: “signs of Life!” Just as the droppings, gross in themselves, are necessary to the delightful existence of birds, so does a free human life inevitably include sin. The price of overcoming loneliness, of being in a world with people, is that those people are going to fail each other in every way. What then?

The floods that begin The Tempest and conclude Piranesi call to mind the Flood in Genesis, whose aim was to renew the wicked world. The odd thing is that on this count, it was entirely unsuccessful. Within a single generation (arguably, within a single day back on land), the survivors are up to their old tricks. And in the story of the Bible and of human history, the vast majority of wicked actions still lie ahead of this event. But God determines not to keep on wiping out the world and starting over, “for the devisings of the human heart are evil from youth” (Genesis 8:21). God discovers (did God not know this before?) that humanity and evil are a package deal, and chooses humanity in love.

Sarah Raphael is similarly disappointed by the promise of renewal offered by the House. Having seen more than her share of evil on duty with the police, she is strongly attracted to its peaceful aura, the same property that gave Piranesi — who, as Matthew Rose Sorensen, was reportedly “an arrogant little shit” — his character. And yet, “I said that this is a perfect world. But it’s not. There are crimes here, just like everywhere else,” she sadly notes, thinking of the bones belonging to people who never got to leave. The call, so to speak, is coming from inside the House.

If sin is inescapable, one option is to bury it beyond memory, where it seemingly cannot matter anymore. This erasure, attempted on the planet Miranda, works on Piranesi for many years — until it doesn’t. The truth will out, some way, somehow. Nothing simply vanishes. It’s not actually possible.

Another is to enact justice, which is also present here — the wave accomplishes it in one way, Raphael in another. Her name, meaning “God heals,” is shared by an angel. Just as the Prophet explained, a thing may change its form but doesn’t disappear. In every way but literally having wings, she is the angel of justice and mercy Piranesi once envisioned, who comes flying in to save him.

But finally, for that which cannot be recovered or made right in any other way, there is forgiveness. This is the challenge posed to Prospero by Ariel, his spirit accomplice, who zips around the island organizing his revenge. As Ariel contemplates Prospero’s usurping brother and his allies, who have been bewitched and bound, a strange sensation comes over him — a feeling which, as a nonhuman, he perceives does not quite belong to him:

The king,

His brother, and yours, abide all three distracted,

And the remainder mourning over them,

Brimful of sorrow and dismay; but chiefly

Him that you termed, sir, “The good old lord Gonzalo”;

His tears run down his beard like winter’s drops

From eaves of reeds. Your charm so strongly works ’em

That if you now beheld them, your affections

Would become tender.

“Dost thou think so, spirit?” Prospero asks.

“Mine would, sir, were I human,” Ariel replies.

“And mine shall,” Prospero resolves:

Hast thou, which art but air, a touch, a feeling

Of their afflictions, and shall not myself,

One of their kind, that relish all as sharply,

Passion as they, be kindlier moved than thou art?

Though with their high wrongs I am struck to the quick,

Yet with my nobler reason against my fury

Do I take part: the rarer action is

In virtue than in vengeance.

Though prompted by a spirit, it is within his human powers that Prospero finds forgiveness. How beauteous mankind is, as his daughter says. It is by such individual acts of grace that the fallen world is continually made new.

As Piranesi leaves his House for a society with billions of Others to relate to, it is this capacity he carries with him. The real enchantment does not reside in the House but in the possibility of restoring communion and love, as often as it is lost, again and again, like the tides rolling out and washing in.

Exhausted by science and tech debates that go nowhere?