April 3, 2020

The test of a people is how it behaves toward the old.

As the outbreak of coronavirus spread this past spring, the world of biomedical ethics exploded with journal articles, consensus statements, and blog posts arguing over the proper criteria for rationing ventilators and other scarce medical resources. The flashpoint came from some of the earliest pandemic guidelines, which appeared to promote discrimination against the elderly — the most likely to die from the disease.

In a widely cited statement, published online in the New England Journal of Medicine in late March, bioethicist Ezekiel Emanuel of the University of Pennsylvania and colleagues argued for a strategy for allocating medical resources that would maximize benefits by both “saving more lives and more years of life.” In practice, rationing on the basis of life-years strongly favors young people, who have more years left to live than the elderly and people with disabilities. Given “limited time and information” in an emergency situation, the authors suggested, saving the greatest number of patients who have “a reasonable life expectancy” is more important than improving length of life for those who do not. The overall effect of this strategy would be “giving priority” to those “at risk of dying young and not having a full life.”

In response to proposals like this, and to even more directly discriminatory rationing strategies that recommended age-based cutoffs for certain treatments, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services published a bulletin declaring that rationing based on age or disability would be illegal for any HHS-funded health programs, including Medicare and Medicaid. Similarly, rightly fearing that a focus on maximizing life-years would reinforce cultural bias that values the lives of the young over the old, many conservative bioethicists spoke out against age-based criteria. For instance, according to a joint statement issued by the Witherspoon Institute, all lives should be treated equally, for all are of “inherent, equal, and indeed incalculable value.” A policy preferential to the young would be unethical, and would send the message that society views the lives of its seniors as less valuable, less worth living, and would lead to further devaluation and inequity.

But while allocation issues put elderly people on the Covid-19 bioethical agenda right from the start, aging itself, as a critical part of the human experience, has hardly been engaged at all. In a pandemic, “difficult and heart-wrenching decisions may have to be made,” observes the Witherspoon statement, and guidance in medical matters will not only reflect the immediate demands of care for the aged but the “sort of society we want ours to be.” But what sort of society is it that properly regards the elderly?

Our response to the pandemic does in fact reveal something critical about our society and how we understand aging — specifically how we refuse to acknowledge the unique circumstances of older adults and to grant them true moral agency. In a time of pandemic and a rapidly aging population, we find ourselves profoundly impoverished. If we want our society to be one that protects older adults and treats them as full social members, then we need not only ethical policies but ethical frameworks in the fullest sense — guides to social practices and family relations and ways of life — that will cease to exclude the old, and reestablish our ties with them.

While the debate over ventilator distribution is no longer urgent (ventilator use has declined sharply for Covid-19 treatment), it illustrates the limitations of current ethical approaches, and it remains relevant as shortages of hospital beds or medications may again arise.

Consider the limitations of the two approaches above to how we should derive the maximum benefit in the event of a shortage. Emanuel and colleagues in the NEJM statement define the greatest benefit in terms of a balancing of lives versus life-years, whereas the conservative ethicists simply define it in terms of lives; yet “lives” here, unmarked in any way, verges on a similarly statistical meaning. In neither model do the ethicists explicitly accord meaningful importance to the life course. Neither acknowledges old age as a specific stage of life with particular vulnerabilities and advantages, characteristic shortcomings and virtues, responsibilities and obligations. Benefit maximization in both models ultimately hinges on the proper measure for abstraction and equalization, whether lives per se or lives qualified by life-years. While striking life-years from the equation avoids bias against the elderly — a just and laudable correction — it does not account for what is distinctive about their lives. The equal persons remain generic, defined from the side of caregivers and bureaucratic calculation. In this framing of the debate, the lives of care receivers are effectively reduced to moral passivity and an empty chronicity, unmarked by social or biological rhythms.

For many, the only quality that marks the aged is their declining capacity to exercise choice. Emanuel and coauthors encourage patients to choose against ventilator treatment when it would contravene the “future quality of life” they would find acceptable. Talk of “quality of life” sounds innocuous, but it is more than a way to speak about the right of a patient to refuse treatment. It has replaced the older formulation of “sanctity of life,” and it conveys moral assumptions about the burden of disability, efficient resource allocation, and the sort of life that is worth living.

Not unique to the pandemic, a choice between life and death occurs in many other areas of contemporary medicine. Most obviously, the choice is presented through the increasing availability of assisted suicide. Yet, as the anthropologist Sharon Kaufman has shown in her 2015 book Ordinary Medicine, everyday practice can also confront older adults with a choice between life and death. When discussing possible transplants or implantable medical devices with elderly patients, for instance, Kaufman finds that doctors frequently frame the decision in terms of added years of life. The surgery, a doctor might say, will give you three more years. In such cases, the patients seem to be offered a choice, albeit one fashioned to indicate that the right decision is medical intervention. Such choices present “improvements in length of life,” to borrow a phrase from the NEJM statement, as the highest good one could choose for oneself, as an end in itself. The meaning of health in a well-lived life is narrowed and replaced with an ad hoc utilitarian calculus of life-years maximization.

The freedom to decide about treatment, to have one’s choices honored, is clearly essential. But without frameworks of ethical reasoning and social practice that can inform the content of the aging person’s choices, the vaunted autonomy rings hollow, even coercive. And such frameworks for an ethical life — frameworks that can speak to the sense of finitude, desire for wholeness, and ultimate concerns of the aged, as well as address their responsibility and obligations to others, to the common good, and to the transcendent — have gone missing.

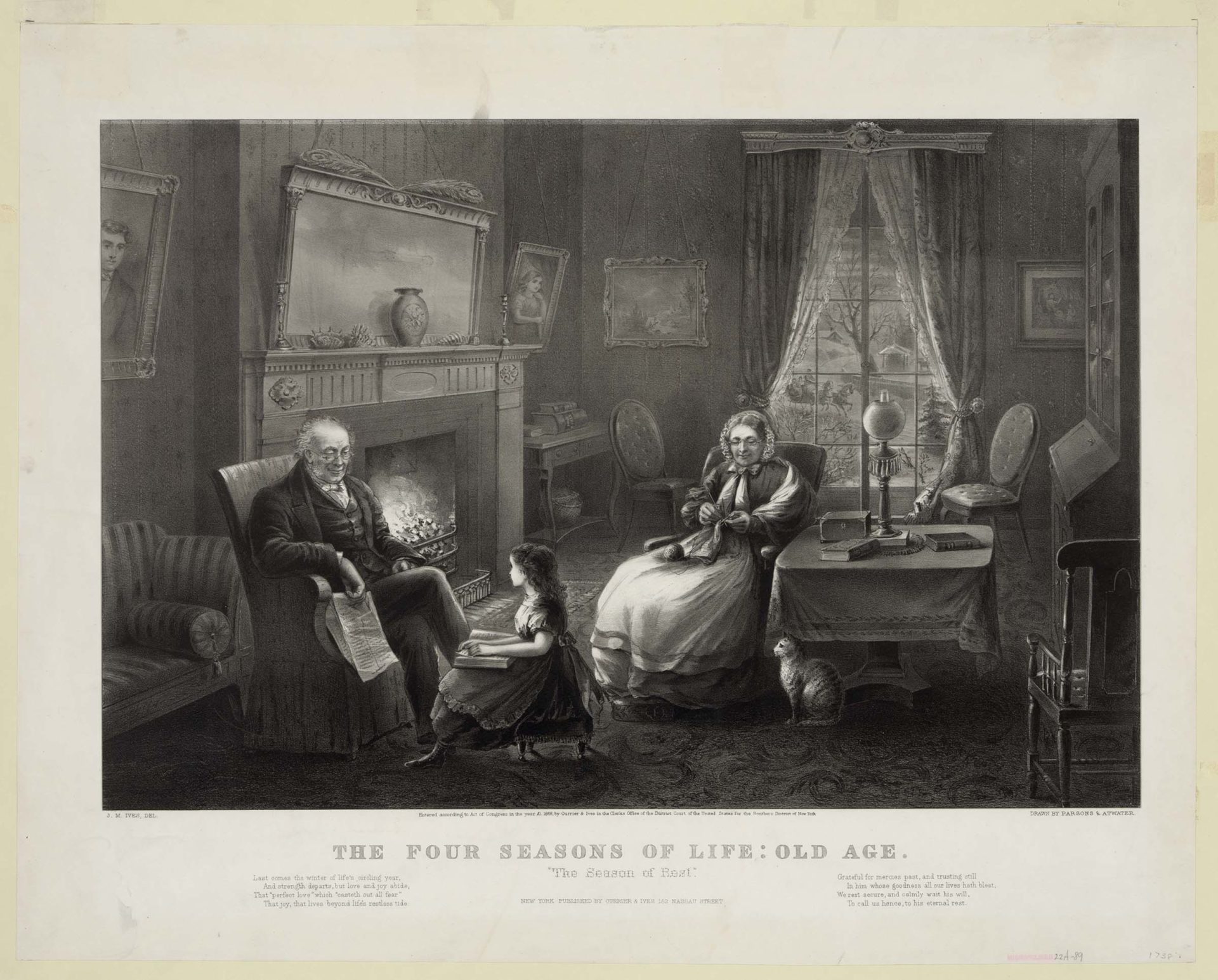

At other times and in other places, traditional ways of life, social classification, and metaphysical order gave shape and coherence to the course of life, providing a picture of aging well. Each period of life had its activities, duties, and forms of flourishing.

The periods of aging, decline, and the approach of death were especially critical. They involve some of the most complex and unsettling aspects of human experience, and so the need for a strong community to provide direction and meaning is most acute. Many social and cultural practices, such as kinship cohorts, rites of generational transition, filial duties to ancestors, hierarchies that honor wisdom, social customs that guide in grieving, and arts of suffering and dying, provided support for this time of life.

Such guidance has not necessarily meant that old people have been given special respect or honor, or that old age has been treated as a social category deserving of special treatment or public concern. Social histories tell an ambiguous and varied story. But norms and practices of aging and dying did provide direction and shared expectations about how to live. And while the ideal form of character in the face of aging and death has varied by time and school of thought, the social philosophies, religious communities, and civic cultures helped guide people in a process of preparing for aging and dying “well.” Despite much variation, the goals were broadly similar.

From antiquity up through the Renaissance, for instance, the different ages of life, including old age, possessed characteristic virtues and vices, rights and obligations. The aged were actively involved in the life of society as responsible agents with important roles. In these societies, largely agrarian, owners would maintain control over their property into old age unless physical or mental decline made it impossible. Even then, they would reside on the property, sometimes within a relationship of explicit contractual obligation with their heir. This time of life was not segregated or marginal or culturally unstable; older people were prepared and knew their obligations and their place in the cycle of generations.

In his treatise On Old Age, Cicero responds to those who lament old age and its constriction of activities and pleasures. They grieve, he argued, only because they value the often illusory pleasures enjoyed by youth over those proper to old age, such as reflection, leisured study, and conversation. And they neglect the important services to the community provided by the aged, like advising in the Senate, directing affairs on their farms, and instructing the young in virtue. In fact, the care for future generations is what most distinctly marks the moral duties and virtues of the aged. As Cicero remarks,

And if you ask a farmer, however old, for whom he is planting, he will unhesitatingly reply, “For the immortal gods, who have willed not only that I should receive these blessings from my ancestors, but also that I should hand them on to posterity.”

Rituals and spiritual disciplines that brought the necessity of sorrow, infirmity, and death into everyday life nurtured the distinct experience of growing old. For example, the memento mori, the reflection on mortality, has been an important practice across many cultures. Anthropologist Robert Desjarlais, in his 2016 book Subject to Death, describes how children in a Nepalese Buddhist community play at death, initiating themselves in a preparation for old age and dying that continues throughout their lives. Greek philosophy in both its Stoic and Platonic forms took the preparation for death as its main activity, and many strands of Christian spirituality took up this philosophical meditation on death, looking to one’s end.

In none of these traditions did such practices encourage a morbid fascination with death or a depressing fixation on nothingness. Quite the contrary, remembering death as an unbending reality raised a sense of generational solidarity and freed people to accept their contingency and live moral lives in the present without fear of the future. This consciousness encouraged all, and especially the old, to eschew fleeting, temporal concerns, like wealth or ambition, for more enduring goods such as knowledge, virtue, and strong relationships.

The connection of the elderly to community and the economy would undergo radical changes in the era of industrialization, from shifts in the occupational system to alterations of family and kinship structure to the rise of welfare schemes and age-graded pension plans. Beginning in the nineteenth century, the life course would become increasingly fixed by chronological boundaries, with the transition to old age marked by the end of productive work in either the factory or the household. Increasing geographical mobility began to undermine stable relationships to place and the integration of grandparents into the daily life of the extended family. Rather than defining the aged as community members with agency and social responsibility, social policy increasingly defined them as persons in need of care. Social science did its part, offering accounts such as “disengagement theory,” which defined as natural the increasing marginalization and sequestration of the old and the need of society to move on without them.

In all these ways and others, and despite greatly improved economic and medical conditions, those advanced in years lost the compelling forms of social standing and engagement that once entailed their duties toward the common good.

In our fluid, shifting culture, common symbols and shared traditions of old age have weakened or disappeared altogether. One need only consider the many current debates that frame aging as a problem to be solved — with “successful aging,” anti-aging interventions, “engineered negligible senescence,” or assisted suicide — to see our communal and ethical quandary. We have precious few resources for even thinking about the enduring questions of a good old age, its meaning as a distinctive stage in life’s journey, and how we might prepare for and embrace the twilight years of life. For the old, aging has become more private, less externally oriented, less bound to pre-established ties to others, and less deeply rooted in a field of ultimate meanings.

What has largely replaced a shared narrative of the life cycle is an autonomous individualism that blurs all age distinctions. While our dominant image of persons as free and unencumbered agents, as masters of choice, is inadequate at every stage of life, it is especially detrimental in the last. Much of what we mean by “autonomy” is to live so as to repress and deny many features of the human condition, such as our dependence on the care of others and the vulnerability of our bodies. Fostered by an illusion of control, we imagine that we are independent of those who sustain us. We recoil from terms that express boundaries, limitations, frailty, or the need for help as “ageist,” and we reject virtually all criteria to inform our choices beyond individual beliefs and preferences. We trap ourselves in a conception of the good and a mode of self-fulfillment that works against any positive conception of living in older age.

Reflecting the cultural valuation of autonomy as the preeminent good, old age is typically depicted in either of two contrasting deficit stories. The first is a deprecating and frightening story of growing old, of our steady deterioration, loss of control and dignity, and then ending, virtually imprisoned, with a medicalized death. A good example is provided by the same Ezekiel Emanuel, writing in the Atlantic in 2014. He wants to die at seventy-five, he says, because the “simple truth” is that “living too long is also a loss.” Old age, he explains,

renders many of us, if not disabled, then faltering and declining…. It robs us of our creativity and ability to contribute to work, society, the world. It transforms how people experience us, relate to us, and, most important, remember us. We are no longer remembered as vibrant and engaged but as feeble, ineffectual, even pathetic.

The evening of life is a shameful defeat, alien to our creative and productive selves and antithetical to the way we want to be related to and remembered. There is reason to believe that this common story, in light of both an aging population and proliferating anti-aging interventions, has intensified and increased negative stereotypes of old age over time.

The second story is an upbeat account of an ageless adulthood characterized by a continuation of self-reliance, productivity, and good health throughout old age, followed by a brief decline and death. This story about “successful aging,” told in both the popular press and in academic papers, is often contrasted with the decline story and presented as a liberating debunking of its negative and stereotypical myths of helplessness and decay. It is appealing because it accurately reproduces what the psychologist Erik Erikson called our “world-image” of “a one-way street to never ending progress,” such that “our lives are to be one-way streets to success — and sudden oblivion.” But far from being anti-ageist, this story of perpetual middle age also devalues the later years as an unfortunate time of life, without value in itself and much inferior to youth. It, too, confuses physical infirmity with moral failing, offers no positive guidance for engaging dependence or vulnerability, and retains the same cultural antagonism to the aging body and approaching death.

These two stories do not exhaust the possibilities, and there have been many important efforts in recent years to envision and live a more authentic and affirming old age. On the scholarly level, the prodigious work of Harry Moody, Thomas R. Cole, and Martha Holstein comes first to mind, but the contributions in literature, film, spiritual texts, and other areas is significant and growing. Yet the deficit stories remain culturally and commercially dominant and dovetail with far-reaching social and economic changes that have destabilized the practices of preparing people for old age — once a central cultural and philosophical task.

In our moment, we urgently need an ethics of aging that centers on the question of what a good life in its later years looks like — an old age that is lived well and that goes well. Toward this ethics there are currently only scattered contributions. Much of the bioethics literature might best be described as ethical reflections on issues that predominantly involve older people. As with the issue of rationing ventilators and other medical resources, this is an abstract ethics focused on patient rights, caregiver duties, and decision-making in the context of formal institutions. However necessary at times, it is not an ethics of everyday life for those navigating their twilight years. A substantive, normative ethics of aging must address old persons in all their complexity. It must go beyond a concern with autonomy, non-exploitation, and even caregiving. It must also consider the obligations and reciprocal responsibilities of the elderly.

While speaking of the responsibilities of the aged might seem inappropriate and even callous, it is in fact essential. We can make no real progress until we do. In a 1985 paper on “The Virtues and Vices of the Elderly” — still one of the few contributions on the subject — the distinguished ethicist William F. May provided the reason why. Excusing the elderly from moral responsibility or judgment, he wrote, “may subtly remove them from the human race” by treating them “condescendingly” and, in effect, as “moral nonentities.” A crucial “step toward reentry into community with the aged,” he observed, will therefore be taken “when we are willing to attend to them seriously enough as moral beings to approve and reprove their behavior” — when we are willing, in other words, to relate to them with genuine respect. Any worthy ethics requires a “positive conception of the soul,” to quote Iris Murdoch, “the purification and reorientation of which must be the task of morals.” We can’t talk about that process, about being good, about the cultivation of virtue unless we also acknowledge the characteristic ways in which the aged might fall short, beginning with the frequently self-defeating attitude of the old to being old.

Moral agency, community integration, and an ethics of mutual obligation are just what the older traditions sought to foster and maintain. They are what we so desperately need now. Again, the pandemic sheds a glaring light on our flawed orientation to the elderly and their complete marginalization. Our failure to care, protect, and serve those in nursing homes and other residential care facilities, where about one percent of the U.S. population lives, has been widely documented and discussed. Covid has raced through such facilities, claiming, by a recent estimate, some 40 percent of all those who have died so far from the disease. Additionally, over the course of the pandemic, tens of thousands of older adults have and will die not from the coronavirus itself, but from the consequences of our response to it. Those suffering from Alzheimer’s and dementia have been particularly hard hit. They often depend on consistent routines and close care from family members, and the disruptions from the unprecedented stay-at-home orders and the visitor restrictions have had devastating — and entirely foreseeable — consequences.

This recent damage from lockdowns only scratches the surface. Social isolation and loneliness are common in the older population and contribute substantially to poor health outcomes and mental distress. A survey of nursing facilities in 2017 found that some 40 percent of residents reported depressive symptoms. In the face of this silent pain, exhortations ring out to build strong connections and find community. Then, in the name of health and safety, the very sources of resilience and the connections that for many make life worth living were severed. Through these disease-prevention efforts we have been bringing about our seniors’ worst fears — not a fear of death but a fear of dying alone; and before that, of spending their final months languishing in near-complete social isolation. Great numbers, far beyond the institutionalized, have been denied the support and consolation of loved ones and the small comforts of everyday routine.

In our unilateral actions we see the profound limits of “autonomy” and the radically deficient understanding of the social nature of the person. Did it ever occur to officials to consult the elderly about their situation, or when “listening to the science” to seek the views of gerontologists and care professionals? With older adults sequestered, consigned to the past, and excluded from responsibility for the common good, we returned with a vengeance to the strong paternalism that the autonomy principle was supposed to abolish. Our actions revealed that autonomy only applies to very particular decisions surrounding life and death and does not extend to the institutional control to which the person must submit. Persons living in care facilities are already confined, already suffer multiple losses, are already often shelved and neglected. “What we owe the old is reverence,” Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel teaches us in a famous address, “but all they ask for is consideration, attention, not to be discarded and forgotten.” Not to be abandoned, as the Psalmist puts it, “when my strength fails.” To foster a genuine interdependence, procedural ethics and autonomy won’t help us. We need an ethics with moral content, one from which the common good has not been jettisoned.

On the one hand, such an ethics, rooted in our shared potentiality and vulnerability, and buttressed by a robust set of cultural concepts and practices, might once again center on the care of future generations. Already in the pandemic, older persons have volunteered to forgo scare resources. Early in the crisis, for instance, popular news stories reported cases like that of the ninety-year-old Belgian woman who died after refusing a ventilator for the sake of access by younger patients. The authors of the joint Witherspoon statement recommend such generosity, that “some patients should themselves consider — not out of legal or even strict moral duty, but rather as [an] … act of generosity — giving up access to something to which they are entitled so that someone else might have it.” However, in the absence of a larger ethical framework of aging, this recommendation appears as little more than an appeal to personal altruism. Within a renewed framework of generational care, by contrast, the courageous forgoing of treatment could reflect an acceptance of mortality, a recognition of gifts received, a readiness to make sacrifices for the common good.

On the other hand, and critically, such an ethics requires that younger generations again become present to and reincorporate those who are in the evening of life. The exclusion of the old has deep roots in our social and economic practices and is becoming ever more untenable as the population ages. Progress will begin with a broader, deeper recognition of our own mortality, dependence on others, and bodily vulnerability, a recognition that would begin to free the young from the fear that drives so many away from engaging with and making a place for the old. The Buddhist and Christian practices of meditation on mortality mentioned above both envisioned aging and dying as social processes requiring the assistance and prayers of family and friends. Being with the elderly is an essential part of one’s own preparation for moving through the life course and for learning the virtues essential to reckoning with the ordeals and finding the joys of old age. At its best, being with the old teaches us about being ready for the unexpected, for the importance of our attachments, and for the value of presence even when it might increase a risk to health.

Such would be an ethics in which care extends from the young to the old and from the old to the young. It would be an ethics framed not in terms of some controlling principle or single model, but in an approach to life in old age that recognizes it as a specific state of life, embraces its distinctive features, and weaves it back into the social fabric from which it has been torn. Anything else, however unintentionally, leads to abandonment.

April 3, 2020

Exhausted by science and tech debates that go nowhere?