It is the Year of Our Lord 1672, and you are an elderly Londoner. At your birth Queen Elizabeth sat on the throne, but your first memories come from King James’s time. Your grandchildren rejoice in the re-opening of the theaters of the city — a notable consequence of the Restoration of the monarchy after the collapse of Cromwell’s Protectorate. These young people delight in the new plays staged with increasing frequency by the King’s Company and the Duke’s Company — and by certain unofficial troupes of actors in disreputable corners of the city. You are certainly pleased that the theater has been rescued from the condemnations of the Puritans; you have visited a few times and the experience has reawakened old memories.

And yet … what those old memories tell you is that the theater now is a pale shadow of the theater of your youth. You remember a time when the plays of Ben Jonson were new, and the plays of John Webster. You were present at the end of Shakespeare’s career, and saw the occasional revival of the mighty verse of Marlowe. You did not own the first great Folio of Shakespeare’s plays, but you borrowed one from a friend and read it with excitement and even awe. And so you feel obliged to tell your grandchildren that, as excellent a thing as it is to have the theaters back, there are no playwrights in England worthy to be compared to the titans of your youth.

Your grandchildren roll their eyes at this. It is always the habit of the old, they tell you, to praise the Ancients above the Moderns, to think that the old times were better than the new. One wit among them reminds you of some words from Ecclesiastes: “Say not thou, What is the cause that the former days were better than these? for thou dost not inquire wisely concerning this.”

“It is an apt quotation,” you tell them. “We that have seen many days invariably extol the ones long past. But the Preacher does not say that the former days were not indeed better. And I tell you that, in the theater at least, indeed they were.”

And you are correct. We who live four hundred years after Shakespeare’s death join you in telling your grandchildren: There were giants on the earth in those days. There was a period, beginning around 1590 and ending around 1620, when the English theater burned more brightly that it ever had before and ever has since. It is true that the old always commend the days of their youth, always see that time bathed in a golden light. But here’s the thing: sometimes they are right to do so. And an important question, for those of us who love the arts and want to see them flourish, is: Why? Why are certain arts better, clearly and obviously better, at some times than others, in some places than others?

It’s frequently said that Ian MacDonald’s 1994 book Revolution in the Head is the finest book about the Beatles. It’s an extraordinary book — highly opinionated, and not correct in all its opinions, but incisive and compelling throughout. I think often about something he says right at the end of the book, as a comment on his extensive chronology of Sixties pop music. Those surveying such a chronology, he insists,

are aware that they are looking at something on a higher scale of achievement than today’s — music which no contemporary artist can claim to match in feeling, variety, formal invention, and sheer out-of-the-blue inspiration. That the same can be said of other musical forms — most obviously classical and jazz — confirms that something in the soul of Western culture began to die during the late Sixties. Arguably pop music, as measured by the singles charts, peaked in 1966, thereafter beginning a shallow decline in overall quality which was already steepening by 1970. While some may date this tail-off to a little later, only the soulless or tone-deaf will refuse to admit any decline at all. Those with ears to hear, let them hear.

Let’s set aside, for the moment anyway, the claim that “something in the soul of Western culture began to die during the late Sixties.” It could after all be the case that music declined while other elements of culture ascended — just as it is perfectly possible that during the post-Shakespearean years in which drama in England declined, other arts and other areas of thought flourished. “Culture” is too vast and complex a thing for all its vectors ever to point in a single direction. So let’s focus on MacDonald’s narrower claim that music, in the Western world, began declining after 1966 — more specifically, though he doesn’t quite say this, after February 22, 1967, when the massive E-major chord that ends “A Day in the Life” was recorded.

This closer look may help us approach a larger question: What are the social and technological conditions under which art may flourish in our time? Even if we grant that genius may appear at any time and in any place — a debatable point — what stars have to align for a genre, a medium, a form to achieve greatness? And: Must we simply wait for such alignments to occur, or is there anything we who love the arts, who have been nourished and challenged and moved by them, can do to push the necessary stars into alignment?

I believe the Beatles achieved greatness when their musical gifts were positioned at the center of a network of resistances — resistances interpersonal, institutional, and technological. And this was true of other major musical artists of their era, though none benefited from the convergence of forces quite as dramatically as the Beatles did.

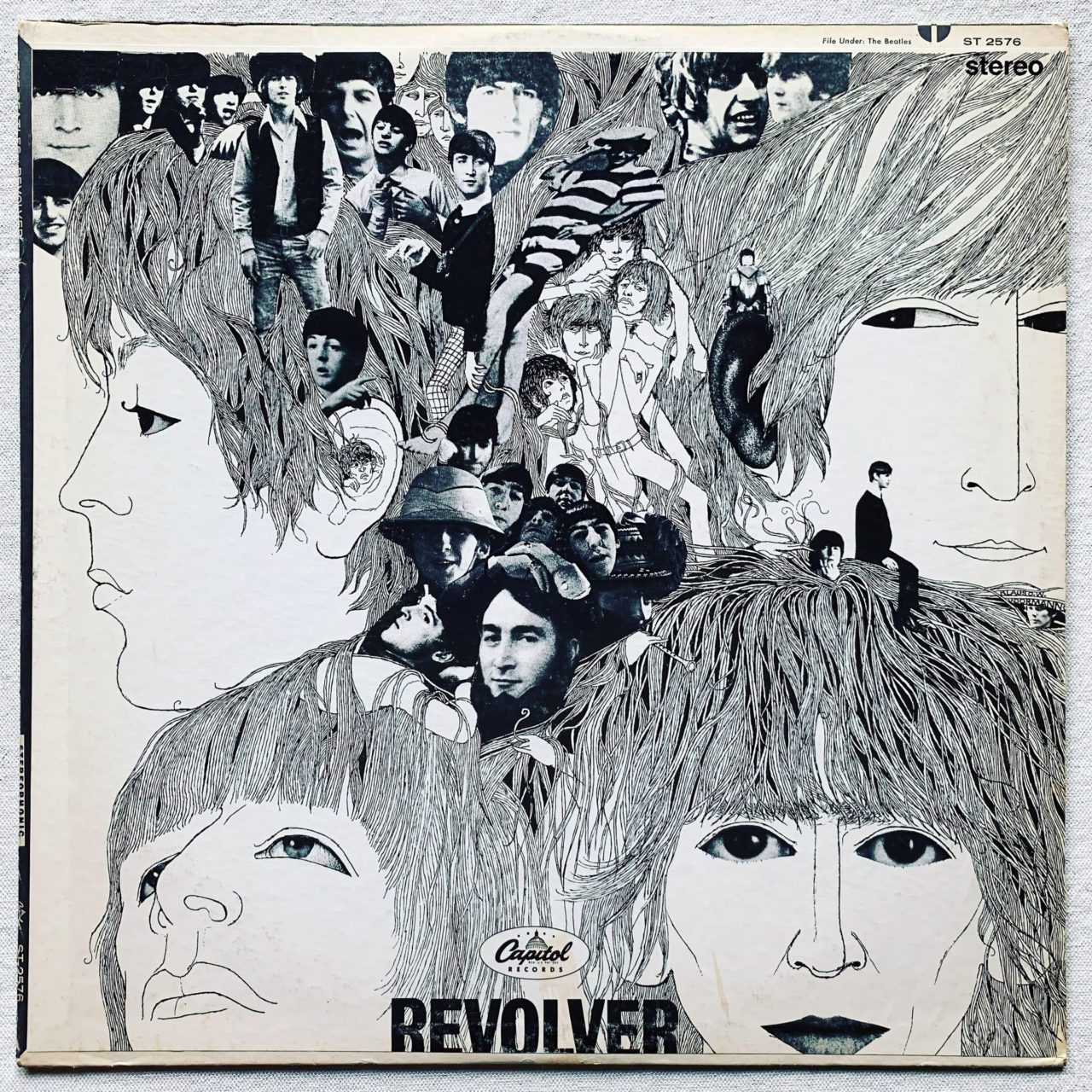

Consider “Tomorrow Never Knows,” the last song on the 1966 album Revolver. To Beatles aficionados this might seem precisely the wrong song to illustrate a thesis about resistance. Does it not rather illustrate the power of liberation from constraint, from social convention, from the confines of the rational mind? After all, this is the first Beatles song to grow directly and fully out of John Lennon’s use of LSD and his encounters with the Tibetan Book of the Dead — as mediated through The Psychedelic Experience, a 1964 book by Timothy Leary, Ralph Metzner, and Richard Alpert. (The song’s first line is a slight revision of one from The Psychedelic Experience, which goes “Whenever in doubt, turn off your mind, relax, float downstream.”) Yes — but everything that Lennon had experienced met resistance in the studio, and it is the tension between his experience of freedom and those resistances that makes the song.

Certainly the song breaks with the conventions of the pop song in several respects. Harmonically, it is built wholly around a C-major drone rather than the usual chord changes; and it’s the first Beatles song whose lyrics don’t rhyme. But like every other Beatles song to this point, it’s short. The longest of their songs thus far were just over three minutes, and while they would eventually stretch beyond that, it didn’t happen often, and even “A Day in the Life,” which in the memory of many listeners is an absolute epic, only takes up five and a half minutes.

The brevity of Beatles songs is a reminder that they were working in a record business that sought to produce and market singles: individual songs to be played on the radio and sold as 45-r.p.m. records. Indeed, Revolver, the Beach Boys’ Pet Sounds, and Bob Dylan’s Blonde on Blonde — all released within a few months of one another — were the essential works that shifted the market away from singles and created what some have called “the album era.” But the Beatles didn’t know that at the time. They recorded short songs because they had always recorded short songs. Yet the brevity of “Tomorrow Never Knows” surely helped to make its musical innovations palatable to confused early listeners. If in recording it the group had had the freedom they would later claim for themselves — the freedom to make recordings like “Revolution 9” and “I Want You (She’s So Heavy),” tracks of which one may say what Samuel Johnson said of Paradise Lost: “None ever wished it longer than it is” — the result could have been disastrous.

(Still, there’s an irony here: The scholar and critic of music Ted Gioia has argued that much music, around the world and throughout history, strives to bring its listeners into a kind of trance state, which requires a song to continue for at least ten minutes. I experienced this decades ago when I heard King Sunny Adé and the African Beats play only five songs over the course of more than two hours. “Tomorrow Never Knows” is explicitly about trance states, but clocks in at two minutes and fifty-seven seconds. This was necessary; but the irony remains.)

The music business, as it then existed, helped “Tomorrow Never Knows” in more ways than simply by enforcing brevity. The EMI studios at Abbey Road were notorious for their slowness to embrace new technologies — indeed, Albert Goldman, John Lennon’s biographer, thought the band was foolish not to record in the more technologically advanced studios in America. But as Ian MacDonald points out, “Abbey Road offered a very particular sound, not to mention an aura of homely English eccentricity which colours and arguably fostered the character of The Beatles’ best work…. With his engineers Geoff Emerick and Ken Scott, George Martin created a sound-world for The Beatles which astonished their better-equipped counterparts in the USA.” For instance, the band and engineers detuned Ringo’s tom-toms to give them a timbre like that of Indian tabla drums and then recorded them with maximal echo, which created a sound that none of the American engineers could figure out how to duplicate.

The whole song was built up in this way, from sounds and effects created painstakingly and combined with even greater care: George Harrison’s simple tambura drone; heavily processed tape loops that Paul McCartney, inspired by listening to the experimental electronic music of Karlheinz Stockhausen, had created at home on his Brenell reel-to-reel tape recorder; John Lennon’s vocal, recorded with a technique called artificial double-tracking — newly invented by an Abbey Road engineer named Ken Townsend — and sent through a modified Leslie cabinet (a kind of speaker/amplifier). One could go on. In every case the artists — including the producer and engineers as well as the musicians — had to work against profound resistance from limited technologies to create the sounds they wanted. Again and again they had to invent new technologies or use existing ones to do things they were not designed to do: the Leslie cabinet, for instance, was typically used to amplify Hammond organs, not human voices. But the sounds they made ended up displaying distinctive textures and timbres that more advanced technologies simply couldn’t replicate. Tommy James — an American singer who was a friend of George Harrison’s — was awed by the sounds produced at Abbey Road. “What they did, everything they did,” he said, “became state of the art” — “state of the art” indicating not the highest level of technological equipment but the highest level of, well, art.

The use of artificial double-tracking to record Lennon’s voice was a kind of compromise: it wasn’t precisely the sound Lennon wanted, but his ideas for how to produce that sound — having himself suspended upside-down over a microphone; hiring a choir of Tibetan monks — were impractical or impossible, so the crew did what they could to approximate his imagined sound. This required some careful negotiation by George Martin, since Lennon was in this season of his life often not wholly rational, but Martin had become expert at such bargaining. Similarly, Lennon’s relationship with McCartney had become increasingly tense, but that tension led to a competitiveness that prompted McCartney to show that he could match Lennon’s willingness to innovate and experiment — and McCartney’s contributions are essential to the success of the song.

In short, “Tomorrow Never Knows” is the product of brilliant musical minds encountering multiple oppositional forces: institutional, technological, interpersonal. In each case the oppositions were strong but not disabling: they could be overcome. But the need to overcome the resistances was in this case one precondition of artistic greatness. “Tomorrow Never Knows,” like all the best Beatles songs, is the product of a collaboration between artists and their network of resistances.

Resistance must be distinguished from blockage, and the resistances that enable creativity from those that impede it. Consider architecture, an artistic medium which, pace Ian MacDonald’s sweeping claim about the decline of Western culture, has arguably — I think certainly — produced more memorable and excellent work in the last few decades than it did in the previous few. This was partly the result of the rise of computer-assisted design, especially as it was pioneered by people working for Frank Gehry. Gehry’s vision of architectural shapes that resemble fabric or the scales of fish was virtually unrealizable — the math required to translate sketches into buildable, stable objects was simply too complex — until Jim Glymph, a member of Gehry’s staff, convinced him to try CATIA: Computer Aided Three-Dimensional Interactive Application. CATIA had been developed for the French aerospace industry, but Glymph adapted it for the design of buildings, and Gehry’s masterful Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, Spain simply would not have been possible without it. CATIA made the path from vision to built environment negotiable-if-difficult, where before it had been altogether blocked.

But today, with imitations of Gehry’s 1990s style proliferating, some of them designed by Gehry himself, we may well wonder whether the computer-aided path has become too easy. We may long for new kinds of resistance, now that the resistances imposed by paper and pencil — the instruments of drawing and of manual arithmetic — have been cleared away.

When young William Shakespeare first came to London in the mid-1580s, the theaters had been around for a decade. They collectively constituted a new forum for a new audience — an audience that prominently included people like Shakespeare himself, provincials looking to make their way in the growing city. (And from farther away than the provinces: for a while Shakespeare lodged in a part of London populated largely by Huguenot refugees from France.) There was no pre-existing repertoire for the theatrical companies to draw on, so they needed playwrights; and playwrights in turn needed material to conjure into dramatic form. The also-new business of bookselling helped with that: chronicles of English history could be had, and recently translated Italian romances. All of them became substantial grist for the young writer’s fantastic mill.

Shakespeare’s writing was always linked with the actors of the companies for which he worked. When the great comedian Will Kempe was one of the Lord Chamberlain’s Men, Shakespeare wrote parts — Falstaff, Dogberry — well-suited to Kempe’s gifts, and, when Kempe left the company, characters of that stripe largely disappeared from Shakespeare’s writing. Similarly, when the Lord Chamberlain’s Men became the King’s Men and began performing not only in the boisterous outdoor Globe but also in the more intimate indoor space of Blackfriars — one of the first theaters to feature artificial lighting — Shakespeare’s dramaturgy changed accordingly. Because the candles that lit the theater had occasionally to be re-lit and otherwise tended, act divisions were introduced, and musicians brought in to perform during these interludes of maintenance. This altered the structures and the rhythms of Shakespeare’s plays, and in this quieter and more decorous environment than that of the Globe, his stories took on subtler and more somber hues. I am inclined to think that even the patterns of his verse — he increasingly often wrote lines that end in unstressed syllables — were affected: such fallings-off of sound could scarcely have been noticed in the noisy Globe. The physical environment in which the verse would be heard reshaped the verse itself.

Throughout his career Shakespeare’s art was sensitively responsive to its surround: he was, to borrow a phrase from the philosopher Charles Taylor, cross-pressured by institutional, political, social, and technological forces, all of which resisted impulse and challenged artfulness. Like the other great playwrights of Shakespeare’s generation and the next, he was situated at the nexus of these many resistances, and took full advantage of the varying energies generated by the varying tensions.

The arts I’ve discussed so far are overtly collaborative ones, but even the arts we think of as more solitary have collaborative elements, and those elements introduce forms of interpersonal resistance. Consider, for instance, those editors who have become for some writers collaborators, most famously Maxwell Perkins with Thomas Wolfe and Gordon Lish with Raymond Carver.

In 2021, the website Literary Hub ran an interview with the writer Joy Williams, whose novel Harrow had just been published. In the course of the interview Williams describes her own encounters with Lish. Lish was famous — in some circles infamous — for the radical pruning he had done to Carver’s stories, the ceaseless cultivation of terse simplicity, and Williams found that he wanted to do the same to her stories: “To me, long ago, when he edited several of my stories for Esquire, it was cut, cut, cut.” Williams didn’t enjoy this, and developed a strategy:

Since I was never adept at cutting and it gave me no joy (when what it was that needed cutting had clearly managed to crawl onto the page out of inattention or desperation) I began to try to write my sentences in such a way that they couldn’t be easily removed. (This of course takes forever.) So I never revise a story after it’s done — all the cutting and rearranging takes place on scrap paper. At the end of the day I might have three hundred words that I can transfer to a lovely fresh piece of paper.

This is a kind of anticipatory response to resistance: Williams knew it was coming, and so internalized the inevitable Lishian response, made it her own, did what she knew Lish would demand but did it her way. It is then a resistance simultaneously given and chosen.

The most obvious way for an artist to choose resistance is to work within a pre-existing form: the sonnet, the sonata, the drawing-from-life. It’s also not uncommon for artists who are proficient in a particular medium or on a particular instrument to refresh themselves by trying something they don’t know how to do as well. Pablo Picasso learned to throw pots when he was in his sixties. Andrei Tarkovsky turned from the expansive powers of cinema to the small and limited palette of the Polaroid camera. After Peter Buck (admittedly a less magisterial artist than the two just mentioned) had for several years been the guitarist for R.E.M., he decided to learn the mandolin. He fooled around with the new instrument and recorded his playing. “When I listened back to it the next day,” he later said, “there was a bunch of stuff that was really just me learning how to play mandolin, and then there’s what became ‘Losing My Religion,’ and then a whole bunch more of me learning to play the mandolin.”

Joy Williams agreed to do the interview with Literary Hub, but asked to write her answers to questions on her typewriter and then mail in the answers. I like this idea and wish to adopt it; it’s a prophylactic against glibness.

In an autobiographical essay in 1973, the Nigerian novelist Chinua Achebe recalled his strict Christian upbringing and his father’s demand that he have nothing to do with the pagans who lived on the other side of the village. He recalled “a fascination for the ritual and the life on the other arm of the crossroads. And I believe two things were in my favour — that curiosity, and the little distance imposed between me and [that other way of life] by the accident of my birth. The distance becomes not a separation but a bringing together like the necessary backward step which a judicious viewer may take in order to see a canvas steadily and fully.” Achebe would later include this essay in a collection aptly titled Hopes and Impediments.

In his essay “Schopenhauer as Educator,” Nietzsche wrote, “These, then, are some of the conditions under which the philosophical genius can at any rate come into existence in our time despite the forces working against it: free manliness of character, early knowledge of mankind, no scholarly education, no narrow patriotism, no necessity for bread-winning, no ties with the state — in short, freedom and again freedom: that wonderful and perilous element in which the Greek philosophers were able to grow up.”

But this does not wholly harmonize with Nietzsche’s overview of Schopenhauer’s life, in which he notes that it was advantageous to Schopenhauer “that he was not brought up destined from the first to be a scholar, but actually worked for a time, if with reluctance, in a merchant’s office and in any event breathed throughout his entire youth the freer air of a great mercantile house” — which is to say, in effect, that Schopenhauer was forced to experience freedom.

Sometimes the removal of constraints creates a kind of resistance. Jazz legend Miles Davis was famous for leading his ensembles by withholding the kinds of direction that musicians were accustomed to receiving. As pianist Bill Evans explains in his liner notes to the 1959 album Kind of Blue, Miles gave his musicians only the most general indications of what he wanted them to play, and gave those just hours before recording: “Therefore, you will hear something close to pure spontaneity in these performances. The group had never played these pieces prior to the recordings and I think without exception the first complete performance of each was a ‘take.’”

But this method didn’t mean that Miles didn’t have a clear sense of what he wanted from his musicians. Writing in his autobiography about the recording of a later masterpiece album, he said, “What we did on Bitches Brew you couldn’t ever write down for an orchestra to play. That’s why I didn’t write it all out, not because I didn’t know what I wanted; I knew that what I wanted would come out of a process and not some prearranged shit…. Any time the weather changes it’s going to change your whole attitude about something, and so a musician will play differently, especially if everything is not put in front of him.” The freedom was the constraint, and the freedom was imposed by a leader whose authority was unquestionable. Miles’s musicians could play nearly anything they wanted, but they couldn’t ask him for more direction.

And it might also be noteworthy that — unlike the Beatles in the later stages of their career, or Pink Floyd in the aftermath of Dark Side of the Moon — Miles and his players never had unlimited studio time, because they didn’t have the budget for it. Miles had excellent artistic reasons for organizing recording sessions as he did, but financial necessity played a role too.

The Beatles’ making of “Tomorrow Never Knows” came at a curious and wonderful technological moment: the sounds generated for the song would have been impossible to create a decade earlier and trivially easy to create two decades later, though “easy to create” in a less compelling way. The analog sources of the sounds generate a kind of “aura” — to borrow a term from Walter Benjamin’s famous essay “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction” — that is difficult to achieve through digital means. It is as though resistance generates through friction a light and warmth to which we humans are drawn.

Precisely the same conditions applied to another radically ambitious project being made just a dozen miles from Abbey Road at the very moment that Revolver was being recorded: Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey, filmed largely at MGM-British Studios in Borehamwood. The visual effects in that film would, again, have been impossible a decade earlier and easy soon thereafter. Among the four special-effects supervisors for the film was a young American named Douglas Trumbull, who proved to be masterful at creating what he would later term “organic effects” — though in 1966 non-organic effects were hard to come by. Trumbull later became a director himself, and designed effects for other to-be-famous films, including Blade Runner, but eventually he became fed up with the film business and stayed away for thirty years.

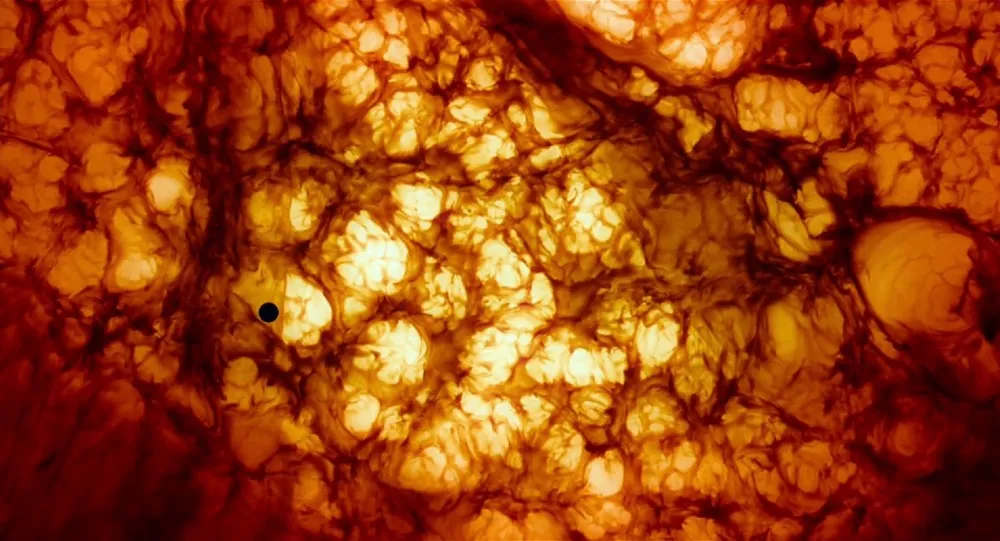

When Terrence Malick was planning the extraordinary cosmic-creation scene in his movie The Tree of Life (2011), he became convinced that he could not get the look and feel he wanted from digital effects, so he called Douglas Trumbull. All the tools needed to create any envisionable image were ready to hand, but Malick turned away from them and sought help from a person who had developed, with great difficulty, more primitive tools, and had done so forty years earlier. “We worked with chemicals, paint, fluorescent dyes, smoke, liquids, CO2, flares, spin dishes, fluid dynamics, lighting, and high-speed photography to see how effective they might be,” Trumbull explained in an interview at the time. “We did things like pour milk through a funnel into a narrow trough and shoot it with a high-speed camera and folded lens, lighting it carefully and using a frame rate that would give the right kind of flow characteristics to look cosmic, galactic, huge and epic.”

The NFT — non-fungible token — is an attempt to use digital means to restore a pre-digital aura. To understand how this works, we might consider the predecessor to the NFT: Once Upon a Time in Shaolin, the 2-CD recording the Wu-Tang Clan made in 2015 and pressed only once. People often say “there’s only one copy” of the record, but the purpose of the whole project is to eliminate the concept of “copy” altogether — there’s just a record. The producers explain: “By adopting an approach to music that traces its lineage back through [t]he Enlightenment, the Baroque and the Renaissance, we hope to reawaken age old perceptions of music as truly monumental art. In doing so, we hope to inspire and intensify urgent debates about the future of music, both economically and in how our generation experiences it. We hope to steer those debates toward more radical solutions and provoke questions about the value and perception of music as a work of art in today’s world.” None of this makes sense: if Wu-Tang Clan had actually wanted to return to the musical practices of earlier centuries, they would not have made a recording — a recording that can, at any point down the line, be copied. In an age of mechanical or digital reproduction, all tokens are fungible. Once Upon a Time in Shaolin is a stunt, as are most NFTs — they are attempts to simulate scarcity, not genuine embraces of resistance.

The kind of social and economic resistance that forced a young Toni Morrison to get up at 4 a.m. each day — before her two children awoke, before she had to get them ready for school and herself for work — to work on her first novel, The Bluest Eye (1970), was not healthy or enabling in any way. That event belongs to the history of blockages, not the anatomy of resistance. Those who experience tractable resistances are to some considerable degree already well-positioned in life. Both kinds of story need to be told.

There are so many potential impediments to the production of meaningful art — race, sex, disability, sexuality, economic injustice, war, physical illness, mental illness, even the mere holding of unpopular views — that it may seem miraculous that anything ever gets made. But then, regrettably, a great horde of people experience no such impediments. Joy Williams says of writer’s block: “Perhaps more should have it. Perhaps the disease, the dilemma, the affliction is trying to tell the writer something. Much that is being produced is unnecessary, indulgent.” The unresisted work is rarely worth examining.

Thinking about these matters brings to mind Kafka’s parable: “Leopards break into the temple and drink all the sacrificial vessels dry; it keeps happening; in the end, it can be calculated in advance and is incorporated into the ritual.”

The paragraphs above — cunningly or at least intentionally organized — sketch an anatomy of resistances. Though I begin with an anecdote about the distant past, for the sake of a Brechtian alienation effect, I draw chiefly on the relatively recent past, for the sake of inspiring hope. If people who are still alive, or once known to those still alive, found that magically enabling network of resistances, then perhaps artists of today can also.

But the conditions under which art is made have greatly changed since that big E-major chord ended “A Day in the Life,” and are still rapidly changing. Everyone knows what the most significant changes, over the last century or so, have been. First we had the shift, still ongoing, from a culture dominated by the reproducible arts of the word and the unique arts of the image to a culture dominated by reproducible images. Then we saw a massive economic shift, from arts sponsored by the open market to arts sponsored primarily by the university and secondarily by certain charitable organizations — a reinvention of the patronage model. Then we had the emergence of the Internet, with its enabling of infinite and frictionless reproduction — which was inevitably accompanied by a powerful and also ongoing transformation of the economic underpinnings of all the arts, but especially music.

Under these conditions, the forces that resist and indeed sometimes block the emergence of great art have undergone relentless metamorphosis. But this much we can say for sure: All of those conditions are now governed almost exclusively by the powers of bureaucratic administration, arithmetical calculation, and algorithmic determination.

The Beatles and their producer George Martin could negotiate with EMI; with the administrative state, as mediated through universities and charitable institutions, with Nielsen numbers and click-through counts, with algorithmic pointers toward what to listen to (and therefore what not to listen to), there can be no negotiation. The intractability of these logics of blockage has driven many journalists and a handful of artists toward mediating institutions that pretend not to be mediating institutions: Patreon, Substack, and so on. Even Salman Rushdie has written stories for Substack. At times this development strikes me as a hopeful one; at other times I think I hear a voice from the year 1971 — just after the setting in of Ian McDonald’s cultural decline — shouting, “Meet the new boss, same as the old boss.”

Perhaps the most important point to be observed from the rise of these mediating disintermediators is this: they promise frictionlessness. They sell freedom, freedom defined as the absence of resistance. They say: When interpersonal and institutional resistances threaten you, we will make your path slick and fast. Indeed, this has always been and continues to be the promise of the Internet: no barriers, no impedance, no resistance. But if the stories I have told in this essay offer any lesson, it is that frictionlessness is often a poisoned chalice. What artists need, when faced with absolute blockage from forces too great to resist, is not the absence of resistance but rather resistances that can be negotiated with — strong but not disabling. Leopards that drink your wine but don’t kill you, and don’t prevent you from returning to the temple.

Musicians might start with a service like Bandcamp, which enables artists to get paid for their work, and to listeners offers algorithmic aid without algorithmic bullying. The world needs Bandcamp for writers, Bandcamp for visual artists. (There are approximations, but none close enough.) It also needs more of something it already has: local or regional creative endeavors — like Belt Publishing, a small press with a Midwestern focus — which operate on a human scale and with human directives and incentives: farm-to-table, but for books. I don’t merely mean that small is beautiful, though it often is, but rather: the non-algorithmic is beautiful. If the doors of perception were cleansed of algorithmic determination, we would see everything as it is: of boundless interest and worthy of endless reflection and representation. The world’s beauty and meaning, its threats and dangers, resist us.

I’ll conclude with one more thought, one more strategy of resistance that may, indeed, be the one that in our noisy moment enables all the others. A little more than a hundred years ago, in A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, James Joyce had his protagonist Stephen Dedalus consider how to evade the “nets” of family, religion, and country. Like Nietzsche, he thought too carelessly about freedom, but he was right to note the dangers of those Powers that capture and bind rather than merely resist. Dedalus said that the tactics he meant to employ in his quest to evade those nets were also three in number: “silence, exile, and cunning.”

Some of the “mediating disintermediators” I have mentioned — the ones who are not merely the old boss in a new boss’s clothing — may offer to artists self-chosen exile from those Powers. But silence is worthy of commendation also. Not necessarily the kind of silence generated by writer’s block, but the silence on social media that arises when people are too busy making their art to conform to the demands of strangers that they take a stance on whatever the political imperative of the moment happens to be.

It is not true that silence is violence. The mandate to comment, to take a stand, to lend your voice — that is a violence against art. We need at least some artists who are too busy thinking and creating to notice what everyone else is talking about. We need artists who never, ever tweet or post or vlog — artists who block what blocks art. When accepting an Emmy for her TV show I May Destroy You in 2021, Michaela Coel counseled her fellow artists, “Do not be afraid to disappear — from it, from us — for a while, and see what comes to you in the silence.” Silence, I think, is the first cunning, the aboriginal resistance.

Exhausted by science and tech debates that go nowhere?