As a child of the 1990s, only three possible jobs existed to my young mind: paleontologist, Chicago Bull, and inventor. The last seemed the most practical of the options, as I lacked the height to dunk or the lateral agility to juke velociraptors. Invention seemed practical by its sheer omnipresence. In grade school we read about Great Men like Thomas Edison and Nikola Tesla, singular visionaries who invented the future on their own initiative.

Television and movies brought it closer to home. Edison and Tesla were distant from me by time and complicated suits, but on the big (and little) screen, inventors were my contemporaries. They were of similar look and means, most notably in their “laboratory.” Pop culture inventors invariably worked out of their garages, that emblem of middle-class mobility. Invention seemed within reach when it was two steps out the front door.

This next generation doesn’t suffer from the same delusion, and their sanity frightens me. Instead, invention has become a secret knowledge, accessible only to M.I.T. grads (and occasionally Stanford). Rather than a meritocratic act of creation, invention in the public consciousness has become elite in nature and limited in scope. The pool of possible inventors has grown smaller, and the depth of their potential shallower. We used to dream of flying cars; now we only hope for slightly less buggy apps.

The fault lies in a subtle yet violent shift in our imagination away from our own responsibility to invent. Pop culture’s vision of invention creates a place where inventions are not only possible but expected. In an ouroboros of cause and effect, our depiction of invention on the screen has shifted from populist obligation to the exclusive right of a technocratic priestly caste. To put it less verbosely, the inventors in film used to look like us; now they look like Robert Downey Jr.

Some of the fondest memories from my childhood are of staying home sick, watching daytime television. One commercial in this timeslot played more frequently than most. It showed a cartoon caveman carving the first wheel out of stone, and the voice-over encouraged viewers to patent their own invention at the advertised company, because clearly copyright law should have come before pants.

The ad, like all daytime television commercials without Wilford Brimley, proved to be a scam. But then the whole myth of the lone wolf inventor was a scam as well. Tesla got his break working for Westinghouse, and Edison had his own sweatshop of engineers cranking out inventions while he was busy electrocuting dogs.

But the unreality is hardly the point. After all, culture is just myth with the skepticism withered away. In printing the legend over the truth, we created a society where inventors did arise. Likewise, through a conspiracy of education and Bob Barker, I believed I could invent a cotton gin and steer the course of human history.

American film and television had no shortage of such inspiring lies. For the sake of brevity and my lacking a Criterion Channel subscription, let’s start with the 1960s. The three most prominent pop culture inventors of the time were, not coincidentally, all professors; one Absent-Minded, one Nutty, and the last so renowned on his little island he was known simply as “the Professor.”

Fred MacMurray’s Absent-Minded Professor Brainard wants to use flubber to make basketball players jump and help out the military, resisting the attempts of a local businessman to exploit it for pure profit. Jerry Lewis’s Nutty Professor Kelp doesn’t sell his transformation serum to the military-industrial complex to create an army of super soldiers and instead keeps it for the more relatable desire of scoring a hot blonde. And if Gilligan’s Island is indeed a microcosm of civilization, as we’ve long suspected, then the Professor is invention at its most altruistic. He never condescends to his fellow castaways, instead using all manner of coconut to ease their troubles. He always has time for a bamboo fashion show or whatever nonsense, even if constructing a raft is a better use of his talents.

While academia is far from a blue-collar field, all three demonstrated their populist bona fides. Only fifteen years from the Manhattan Project, the public still saw invention as the domain of the university. But more importantly, they saw academics as the domain of the people. The GI bill wedged a work boot into the college door — it was no longer just the nesting ground for George Plimpton types. Here the professors use their inventions for plebian good: finding love and helping white kids dunk.

But in the 1970s, stagnation didn’t lend itself to an inventing ethos. Jimmy Carter is a good man, but he built houses, not jetpacks. The true run of populist inventors came from Carter’s defeat and the following dozen years of Republican administration. The image of Americans as independent innovators in the Eighties was a proxy battle of the Cold War; if Soviets were but a facet of the wider state, then each American would be the whole of America unto himself.

It is here, in the 1980s and early 90s, where we start to see the rise of the “garage inventor” in film. This is not someone who invents garages, mind you — garages are like crabs in their simple perfection. Rather, the garage inventor is the middle-class inventor who operates out of his suburban garage, sending colorful mushroom plumes out the window to the fury of the neighbor. (The neighbor is invariably played by Charles Grodin, or his non-union equivalent.)

Doc Brown from Back to the Future is the platonic ideal, even constructing his time machine out of an automobile. Other examples include the dad from Gremlins, Belle’s dad from Beauty and the Beast, and Rick Moranis as the dad in Honey, I Shrunk the Kids. The last of these actually works out of his attic, but an attic is spiritually a garage. We store Christmas decorations in both, which is the true and only litmus. It seems there are at the time no garage inventor moms on screen. The man alone is to provide for his family in the most impractical way possible. Harrison Ford in Mosquito Coast portrays a more horrifying possibility for the garage inventor father, but it was morning in America and thus too early for bad news.

The populist inventor even extends to desolate locales such as outer space and Canada. In Mystery Science Theater 3000, Joel is a janitor forced to watch terrible movies in his satellite prison. Yet he still manages to create his robot friends to ease his loneliness. For the best inventor of them all we must look to The Red Green Show. Mr. Green’s Canadian know-how enables him to take junkyard scraps and fashion low-cost alternatives for the working class. He isn’t backed by venture capital; duct tape provides the only support he needs. While these shows had a tenuous grasp on reality, the blue-collar tinkerer protagonists were our access point. No matter how outlandish their creations got, we still believed these lowly proles had it in them.

Classifying the garage inventor is like cataloging all the varying breeds of an extinct marsupial. As big tech has taken over the economy, and indeed our lives, the garage inventor has ceded his throne to the wealthy technocrat.

The logic tracks; as we transition into a service economy, we have yielded the baseline mechanical comprehension to change our oil, let alone build a time machine out of a DeLorean. “Tech” has stepped into the vacancy and assumed the role of “inventor,” partly out of its own self-regard and partly because there’s no one else to fill the vacuum.

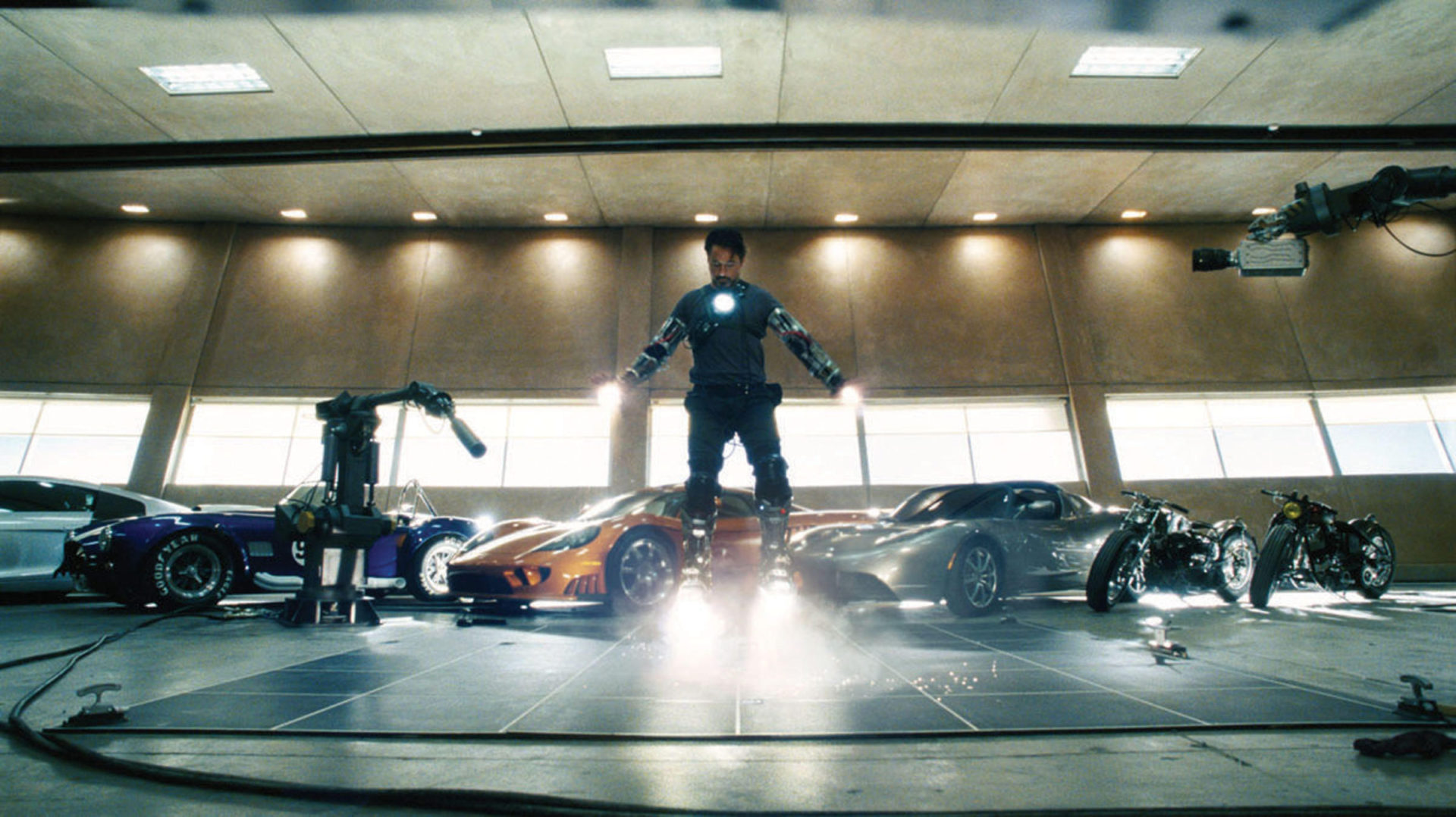

Let’s look to Marvel movies, or as kids call them these days, “the movies.” Tony Stark operates in a garage, albeit one that lies beneath his Malibu compound. He is a beloved character not for his relatability, but for his arrogance. He defines himself by his isolation; no one is as clever or rich as he is, but he’d like to see you try. His altruism is set on his terms. He has, as he famously decreed at a congressional hearing, “privatized world peace.” We see the same with Hank Pym, a.k.a. the original Ant-Man. Although helping mankind, he uses his shrinking technology for himself and his select protégés. With great power comes great responsibility, but that power belongs only to the mogul who invented it.

It applies to non-superheroes as well. Ex Machina has the structure of a mad scientist tale, with a lonely traveler uncovering horrors in a remote laboratory — classic stuff. But here the lonely traveler is a programmer, and the mad scientist a mad tech CEO. The beats remain the same, yet we don’t believe in a man of pure creativity anymore. Now he must have stock shares. In the more recent M3gan, Gemma indeed makes the diabolical robot doll at home, rather than her professional lab. But she is also an M.I.T. prodigy who struggles to relate to her niece’s down-to-earth needs. She seems more interested in her career advancement and bourgeois Seattle real estate. Oddly enough, all these inventors create tangible products while aping techie aesthetics. Our visual language has changed, yet we still long for an invention that isn’t in the cloud.

Today’s real-life techies feel the same longing. It’s easy to forget that even the playground of the rich was raised on the same media of the garage inventor, and thus has the same shorthand. The modern techie dresses in the same disheveled manner as Rick Moranis — now he just pays top dollar for the privilege. Tech entrepreneurs like to state proudly how their startups began in their parents’ garage. They neglect to mention that their parents threw in 1.5 million dollars in seed money with the garage. It’s rude to talk about finances.

Just chart the warring soul of Elon Musk. He is torn asunder between his desires to be a Bond villain and a garage inventor. His TV and film appearances illustrate the struggle. On one hand he appeared in Iron Man 2, with Tony Stark treating him as a rare equal. Yet he also cameoed in Rick and Morty, his cartoon avatar working alongside garage inventor Rick Sanchez. Elon splits the difference in his superiority and populism. It results in a man who owns Twitter but uses it only to share Reddit tier memes.

But as with Edison and Tesla, the technocrat inventor archetype is more hype than substance. I won’t deny the real results of modern technology. My great-grandfather would clutch his hat at the breadth and distance of strangers I can hate every morning. But tech hardly invents, it rarely brings something new to the table; instead it consolidates and innovates already existing tools. In the book Zero to One, Peter Thiel refers to this as “horizontal progress.” Just as I would use my lateral agility to sidestep velociraptors, tech can innovate on its level but doesn’t take the step upward to actual invention, which Thiel naturally calls “vertical progress.” Silicon Valley can work miracles in an app, but it’s still just an app. They can combine your Internet and your phone, but unlike Alexander Graham Bell they can’t seem to invent anything like the phone itself.

The prognosis is bleak. Invention inspires entertainment, but entertainment too inspires invention. Without Star Trek we wouldn’t have had nerds inventing the future. This next generation of pop culture doesn’t have the same egalitarian subtext. We will never be Spock, but new media won’t even let us make the presumption. We risk cycling through the inventions we already have, shrinking them smaller and smaller until we have nothing left. Down that path lies stagnation, decadence, and inevitably a Ross Douthat column.

But the beauty of the life-changing invention is that you don’t see it coming. One day you’re gnawing loaves like some feral beast, then a bold thinker cuts the bread into thin wedges that she calls slices. The future could change in a heartbeat, a miracle solution to a problem we did not know existed. I would love to have my thesis invalidated. And yet I wait for the Fonzie elbow to smash the jukebox and get the music going again. That’s the human touch.

September 25, 2013

Exhausted by science and tech debates that go nowhere?