The instinct for self-preservation, typically buried under the distractions of daily life, surfaces when pondering all the things that can go wrong during surgery. In an ordinary state, most people’s thoughts work logically. But in the surgical holding area, they often move by association, as in a dream. A word, an object, a color can awaken a host of unpleasant feelings.

I once had a patient who, when a nurse ran by, thought another patient in the operating room was having an emergency. It scared him so much that he refused to go through with his own surgery. In fact, the nurse was running to grab a bagel on her break.

Such anxiety before surgery has grown worse over the years. During the 1980s, when I trained in anesthesiology, patients scheduled for even minor procedures often came to the hospital the night before. Anesthesiologists would prescribe them a sedative — usually Demerol — for the following morning to ease their journey from the wards to the operating room. Lying face up on a rolling gurney, halfway between wakefulness and sleep, patients saw the ceiling move past them in an endless taut ribbon. Words reached them, at best, through a dense fog, while the waves of sight and sound rocked and lulled them.

This changed with the advent of outpatient surgery, where patients go directly from their homes to a surgical suite in the community. In 1980, only 16 percent of surgeries in the U.S. were outpatient. Today, the number is around 60 percent. Even patients scheduled for major surgery at a hospital, and destined for what is called “planned admission,” often come to the operating room directly from home.

With roughly half of all surgical patients suffering from preoperative anxiety, the problem has caught the attention of researchers. Some studies suggest that the associated rise in blood pressure and pulse worsens postoperative outcomes; others have shown a higher incidence of postoperative pain, nausea, and vomiting in anxious patients, as well as delayed recovery and prolonged hospital stay.

“Better communication” is the advised corrective: after coaxing patients into admitting their fears, anesthesiologists are encouraged to give patients more information — about going under, the potential risks, and the pain they will feel after surgery. Yet this advice overvalues the benefits of professional talk. It is in the preoperative holding area that the effort to teach people out of their anxiety fails most vividly. It also exposes a shortcoming in how physicians today are taught to imagine their roles.

Patients who fear dying under anesthesia often appear cold and quiet. They look as if they have no intention of hiding anything, but also no intention of telling anything. They keep up the camouflage by exerting all their strength. If one looks closely enough, one can see the rapid pounding of their hearts in their bulging neck veins. Their speech, when they do talk, is often jerky and brief, accompanied by quick, keen glances and abrupt movements.

Talking to patients about their fear is like probing around a sore spot. On the one hand, it risks raising their fear to the level of the real, making it a legitimate object for contemplation. Yet if one fails to show sympathy, some patients feel alone in the world, which also magnifies their fear.

Many anesthesiologists try to calm their patients by telling them how safe anesthesia is. But the method often fails because a patient’s reason turns against her, becoming part of the problem. The patient concludes that while anesthesia may be safe in most cases across a large population, that fact has no bearing on her particular case. Some patients even imagine possessing foreknowledge of coming events. They see too much cause in everything, not unlike how a madman reads conspiratorial significance into empty activities. One patient of mine feared that because a nurse had mispronounced her name, the surgical team might confuse her with another patient and perform the wrong operation. Another patient feared that because an IV pole had accidentally collapsed downward a few inches, producing a loud bang, the equipment at the hospital was substandard, thereby putting her at risk.

Trying to appeal to a patient’s reason in such cases leads nowhere. It is like talking to a paranoid who connects one thing with another in a map more elaborate than a maze. In one case, a man asked me if I had ever lost a patient. When I told him no, he shrugged and said that if I had, I probably wouldn’t tell. Even if true, he said, it didn’t mean I might not lose a patient in the future. In fact, he said, I was putting him at risk because I had never lost a patient. If you were rolling a pair of dice, he said, and two sixes don’t come up after several throws, they are due to come up sooner rather than later — just as a patient’s death would.

When information fails to calm patients, most doctors try to comfort them. But anxious patients are first and foremost reasoners, and their reason pulls off the doctor’s disguise, especially if the doctor is a poor actor and his comforting words have a studied, bookish flavor, which destroys the illusion of friendship that the words were intended to create. Besides, promises made must be promises kept, and anxious patients cannot help but notice how their anesthesiologist refuses to give out guarantees despite warmly saying, “I think everything will be fine.”

Past generations of anesthesiologists took a different approach to patient anxiety. They stoked people’s propensity toward faith, in a general sense.

Most sick people refuse to believe that illness assails them for no reason, and look outside themselves for an explanation. Some people look to God. Yet even among secular people, falling ill is inseparably linked to spiritual thoughts and feelings. They, too, imagine powerful forces beyond their understanding or control, such as nature or fate, as the reason for their predicament. They blame these things; at the same time, they secretly pray to them for their release. In their distress, they inevitably seek someone to mediate between themselves and these powerful forces, a wise and experienced person who might conciliate the forces or even resist them. In ancient days, that mediator was the priest. In modern times, and until recently, that mediator has been the doctor, who took over some of the priest’s functions.

By tapping into this quasi-religious sentiment, the priest–doctor helps to ease a patient’s fear of dying under anesthesia. Patients know that most good medical outcomes can be credited to a doctor’s smarts. But there is a part of many patients that wants to hope and believe that their doctor is also somehow in touch with the universal scheme of things, is gifted with mysterious powers, and is perhaps even a “born healer,” rather than merely someone who passed a few examinations in medical school and thereby gained the authority to ladle out medicines and prescribe treatments. Far more than we are wont to imagine, the elemental instinct to look upon illness as somehow tied to the extraordinary, and to view the priest–doctor as someone who can communicate with the extraordinary, even wrestle with it, persists to one degree or another in all of us. For patients, imagining that their anesthesiologist has special powers to resist the forces of nature or fate, or suspend the laws of probability, thereby keeping them from dying, may seem outdated, but it does calm them.

I once took care of a middle-aged woman who feared dying under anesthesia because so much else in her life had gone wrong. Quoting anesthesia safety statistics to her had no effect, so I tried a different approach. Ceasing to be the clerk who conveys facts and becoming instead the vital man from whom power goes forth, I told her she had nothing to fear from fate, or what she called “her destiny.” I even quoted from St. Augustine’s repudiation of the notion of fate in The City of God. She was somewhat taken aback, in part, I think, because I had stretched her mind in a way she hadn’t expected, but also because she saw me in a new light. At that moment I was no longer just a well-trained technician; I was someone gifted with second sight. I was no longer just an expert on disease; I was the strong-willed medicine man with the power to see through walls, to understand the unknown, and to pinpoint fate’s weak spot.

It worked. She calmed down, and both her heart rate and blood pressure returned to normal.

Fear of having pain after surgery is another major reason for anxiety before it. It is hard for a doctor to conjure this elemental fear out of existence just by giving patients information.

A priest–doctor works from a different angle. For example, instead of telling anxious patients that narcotics will be made available to them in the recovery room, priest–doctors emphatically promise them. Like God in the desert promising manna from heaven and water from a rock, they promise patients whatever they want, and more than they could want. The priest–doctor is more than just a service provider — he dreams the patient’s dreams, he becomes the patient’s champion, preacher, and salvation.

The priest–doctor also tells patients that pain involves more than just the firing of nerves. Pain testifies to one of life’s fundamental contradictions, which is that people want to live happily, but it is hard to do so, as so much gets in the way. Pain after surgery highlights this contradiction, as happiness, always desired, now becomes physically impossible, which can raise pain to the level of torture. When priest–doctors tell patients in advance that they understand not only how painful pain can be, but also how frustrating it can be, and that they will treat that frustration along with the pain, using special sedatives, because they understand its origin, they cease to be technicians and become people endowed with more wisdom than is normal — people wise in the lore of life.

In the same vein, all priests recognize that to gain followers they must grant people more than a passive role to play in life. A priest utters the sacred words, which can have stupendous effects, summoning the spiritual forces within a listener and prodding him to great feats. The listener ceases to be the anxious person who passively awaits fate, and becomes the inspired being who imagines possessing immeasurable powers.

The priest–doctor works the same angle when managing people’s fear of postoperative pain. She starts in the surgical holding area by telling anxious patients that any pain they might feel is unique. Although they will be asked in the recovery room to rate their pain using a common scale, their pain will have a quality to it that no one else will truly understand.

The very idea of something being both special and poorly understood attracts patients’ attention and enhances their expectations. It also leaves their minds unsatisfied and wanting more.

The priest–doctor then tells patients how for centuries experts puzzled over the interrelationship between mind, body, and pain, but that the mystery has been solved by a miraculous simplicity: to a high degree, pain is a mental experience, over which patients have some control. In other words, pain is a self-imposed belief as much as a reality.

The idea works like an intoxicating vapor on patients’ imaginations. True, an aspect of it is a bit farfetched, but if faith is the father of miracles, anxiety is the mother, and anxious patients instinctively gravitate toward the idea.

Finally, the priest–doctor tells patients that not only will their pain be unique, but because it is unique, and because pain is very much a mental experience, they are their own best advocates. Not only must they prepare themselves psychologically to “think” their pain away in the recovery room, they must also be ready to assert themselves when this proves impossible. They must not be shy or passive — they must demand pain medication, they must tap into the productive energy of their new self-knowledge.

Empowering patients titillates them in the most delicate way, both soothing and stimulating them. They grow possessed of the idea — or, rather, the idea possesses them — that they are the invisible kings of their own minds, where pain is felt. Convinced they have learned something important, they cease to see themselves as victims who passively await some punishment, and instead assume an undertone of independence, imagining how they will take control of their pain later in the recovery room.

The priest–doctor also alleviates a third major cause of preoperative anxiety. Unless scheduled for a major operation, most patients fear anesthesia more than they fear surgery. One of the most intense fears is really a cluster of related fears, including the fear of losing consciousness, of being paralyzed from anesthesia, of being aware while under general anesthesia, and of revealing personal issues while under anesthesia. All these involve the “fear of losing control” — control of one’s legs, one’s speech, one’s power to move under threat, and the power of consciousness itself. None of these fears responds well to rational persuasion.

An anesthesiologist can do little to reassure patients who fear being paralyzed from anesthesia other than to emphasize the rarity of the event. The same goes for patients who fear being aware while under anesthesia, or talking while under anesthesia, although here patients can be reassured that they will be kept “deeply asleep,” with monitors to prove it.

But the priest–doctor has more to offer. During my career, when citing statistics on paralysis or awareness under anesthesia, I sometimes rattled off the numbers quickly, in a succession so rapid that the meanings likely eluded patients, as in a swiftly spinning roulette wheel where the numbers become indistinguishable. That was my intention, as I relied not on the numbers but on my general impression to ease the patient’s anxiety. A doctor who lacks conviction lacks the power to convince; conversely, a priest–doctor who carries his head commandingly despite knowing that a chance of failure exists makes his optimism irresistible. In my case, the numbers I reeled off were simply a way to give shape to the supreme feeling of confidence I wanted to transmit.

The priest–doctor has more success when dealing with patients who fear losing consciousness. These patients are afraid because life has taken a firm grip on them. They love all the things that bring them happiness, so intensely that sometimes they almost seem convinced that no one will love life as much as they have. True, some patients express the opposite feeling when they arrive for surgery. They are weary of fighting, weary of exercising their will, both at home and at work. There’s not much they love in life at that moment, and they look forward to a period of anesthetic-induced oblivion. But for other patients the threat of losing their conscious connection to what they love, even for just a short time, terrifies them.

I once took care of an anxious man who needed sedation and possibly full general anesthesia for his hernia repair, and who had a fear of losing consciousness. I tried reasoning with him. I told him he lost consciousness every night when he went to sleep, and that if he wasn’t afraid of falling asleep, he shouldn’t be afraid of anesthesia. Somehow this was different, he replied nervously.

In the operating room I sedated him slowly to recreate the experience of falling asleep naturally. All the while he kept crying, “I don’t want to be knocked out completely, okay, doc?” But every second he sensed himself moving closer to that shadow line that separates conscious life from unconsciousness, causing his heart rate and blood pressure to climb precipitously.

It helped that I kept talking to him during his surgery. By staying in verbal contact with him, I became for him the symbol, the constellation, to guide him amid the circling waves of the whirlpool he imagined drowning in. No matter how sleepy he became, his mind always encountered me, which seemed to calm him. As his priest–doctor, I was the firm and fixed reminder of conscious life and all that he loved.

His surgery went longer than expected. He was in pain and needed full general anesthesia. Still, he fought against the idea. I could have tricked him and, without warning, slipped enough drug into his intravenous to knock him out. But this seemed unethical. Instead I created for him an illusion. I told him he was, in fact, already unconscious, and that he was listening to me in his sleep; I was just going to make his sleep a bit deeper. And to some degree this was true, for in drug-induced semi-consciousness the boundary line between dream and reality vanishes. It is also a confused state of mind in which a patient can be convinced of almost anything.

The patient smiled and yawned. It seemed as if he were dreaming that the deed was already done, and that he was already asleep, while somehow still being awake. A dream, yes, but none more confidently believes his own dream, and allows hallucination to carry him so near the boundary of self-deception, than the semi-sedated patient. The man’s heart rate and blood pressure remained normal as I gave him the final dose of anesthetic to put him under.

When he woke up after the operation, he told me how wonderful the anesthetic had been, filled with odd images and vague impressions, never certain if he had been awake or asleep, and all the while listening to me talk, each word of mine rounding in the air and slowly melting away as a new word followed. The illusion had worked.

Anesthesiologists who try to reassure anxious patients through information alone are like the lawyer who went to his dentist and began to describe his toothache with the words, “Gentlemen of the jury!” They are out of sync with the moment.

The same error permeates medicine more generally. At times, a scientifically trained doctor must also be a priest–doctor, yet none of today’s physician models cultivates the idea. In fact, they all work against it. The patient-centered care model puts patients at the center of decision-making while turning the doctor into a mere cabinet minister. The business model transforms patients into “consumers” and physicians into “service providers,” on par with travel agents and stockbrokers. The egalitarian model puts doctors and patients on an equal footing, leaving doctors feeling almost embarrassed when patients, typically of an older generation, admit reverence for them. The scientific model views doctors as glorified computers and precision robots.

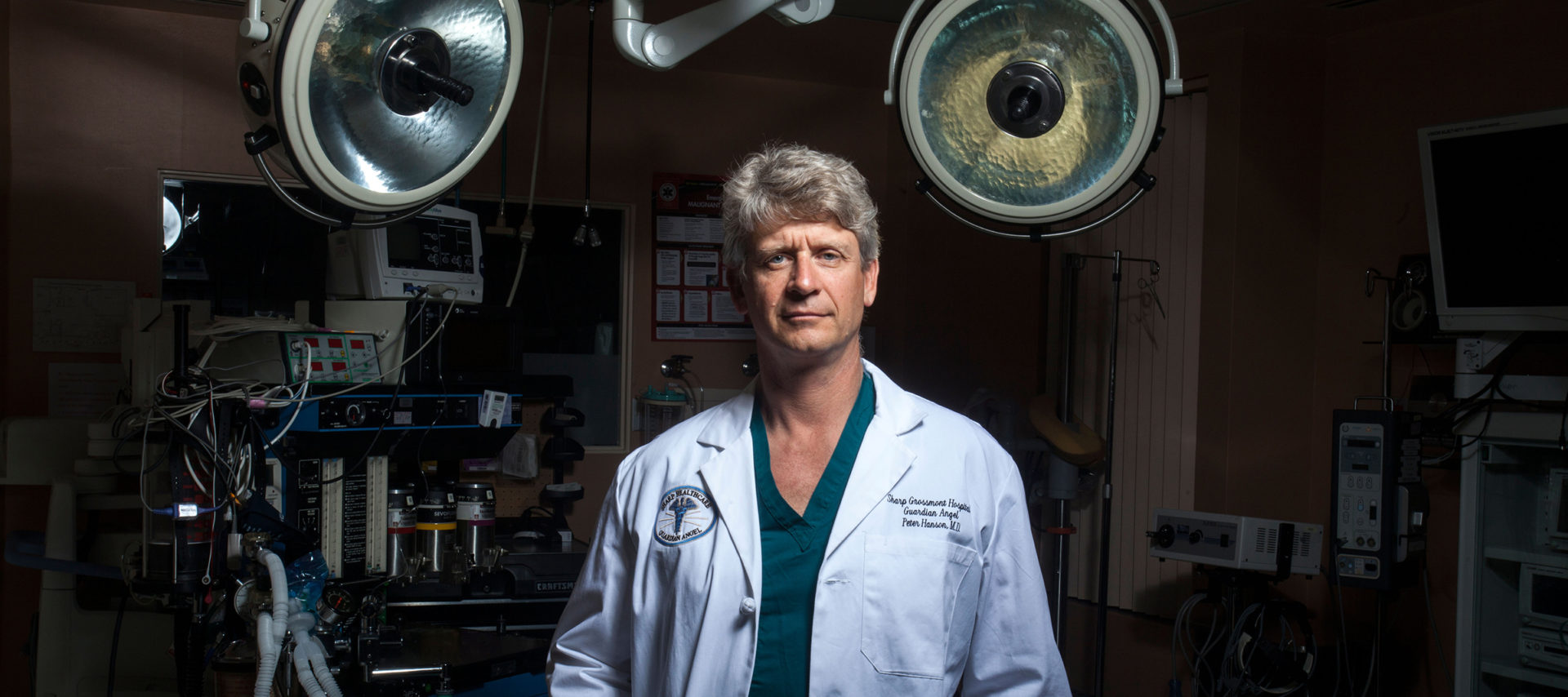

All these models have one thing in common: a refusal to acknowledge that part of a doctor’s role is to cultivate acts of faith, that he or she is a priest who speaks the right words and knows the miracle of the logos, who dabbles in illusion, and who enhances his or her position of authority by an assumption of mystery. This is why all these models — even the scientific model, to appease the egalitarian one — tend to reject medicine’s one priestly symbol: the white coat.

Regarding the problem of preoperative anxiety, if anesthesiologists refuse to act as priest–doctors and instead focus solely on giving out information, then the only solution is pharmacological: lightly sedating anxious patients with a small dose of a Valium-like drug before coming to the surgery center or hospital. Not all patients — for example, those with problem airways, who are at high risk for respiratory depression, or who need to be awake and responsive during their surgery — would be candidates for this solution. But many others would be, assuming they are not driving themselves to the surgery center.

But there is a bigger problem with this solution. The whole direction of discharge planning over the last forty years has been to lessen the time patients spend in operating and recovery rooms. This approach has shaped much of anesthesiology. The new inhalational gases were designed to wear off much faster than the older ones. The new short-acting narcotics and non-narcotic pain relievers have the same purpose, as do the short-acting muscle relaxants. To a high degree, propofol replaced thiopental as the primary induction agent for anesthesia because this made patients much less groggy after their surgery. All these improvements lessened time in surgical and recovery rooms. They helped save money — which is important, given tight health care budgets. A sedative given to anxious patients prior to their surgery seems like a step backward.

But it may also be a necessary act of compassion if the priest–doctor model is now passé. When patients are anxious before surgery, they are simply behaving like normal human beings. When they willingly surrender control of their bodies and minds to their anesthesiologists — a leap of faith — they play the role of laity, their longstanding role. The problem is with the doctors, who, by shirking their priestly duties, fail to play theirs.

Keep reading our Summer 2025 issue

Uncle Sam’s dream house • What toasts your bagel • Tech & marriage • Subscribe

Exhausted by science and tech debates that go nowhere?