George Jetson is alive. No, not literally, of course. But in the world of the famous 1960s TV series, set in 2062, George Jetson was forty years old. This means that the Jetson patriarch was born in 2022. For people of a certain age, this is depressing news. It’s a cartoon from childhood about the far future — and the far future is now here.

The year 2022, then, was one of ignominious milestones for humanity’s future in space. Though the year of the Jetsons is still far off, our society then will almost certainly not look anything like the show’s Orbit City. And there was another milestone, too: December 2022 marked fifty years since the last Apollo mission sent men to the Moon, an anniversary that seems to represent a colossal failure of science, technology, and progress.

In early 1960s America, it was perfectly reasonable to imagine a world a century later with flying cars and permanent human space habitats. When Yuri Gagarin and John Glenn were orbiting Earth, you could forgive writers for their imaginations. The show was conceived during a period when people were breathtakingly optimistic about emerging technologies. But 2022 being the year of George Jetson’s “birth” is a funny yet startling reminder that such a future never came true. The cartoons many of us watched growing up with big dreams of the future have remained just that — cartoons and dreams. And people who were born after Gene Cernan and Harrison Schmitt took humanity’s last steps on the Moon are now old enough to have grandchildren.

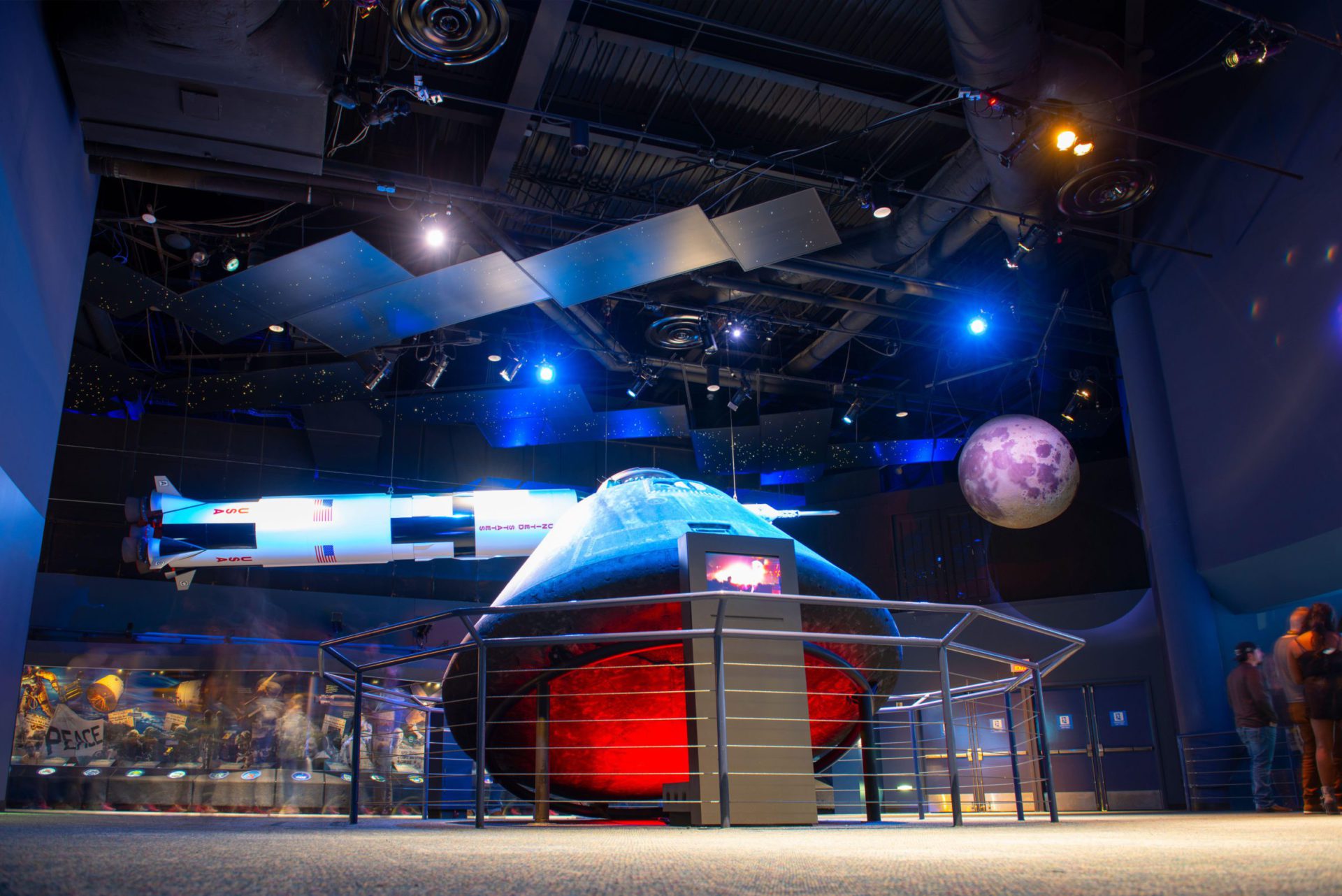

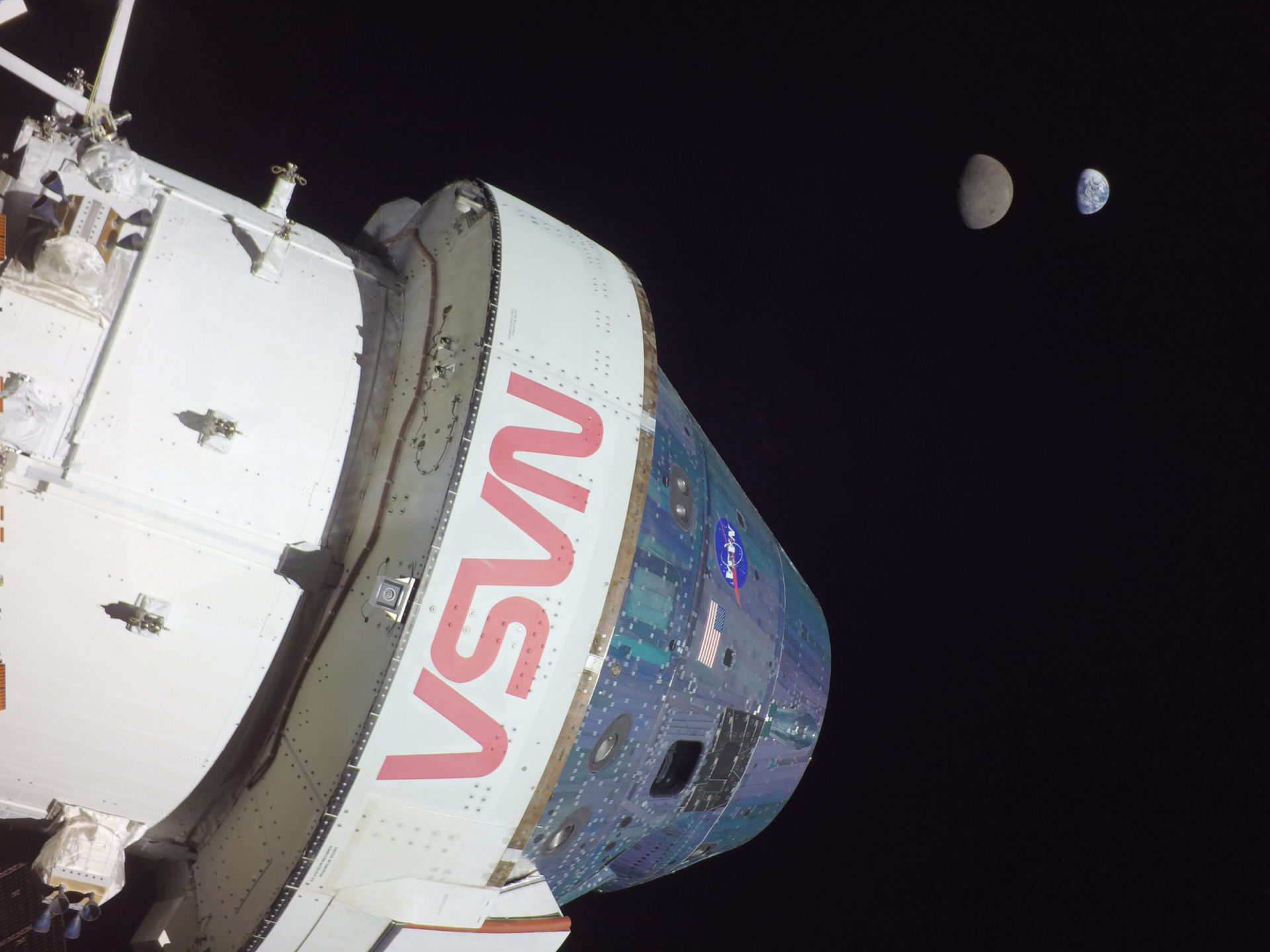

But despite all this, 2022 may actually go down in the history books as the year we finally brought this long delay to an end. With the recent success of Artemis 1 — NASA’s test of the Space Launch System rocket topped by an Orion capsule, which splashed down on December 11 after a successful trip around the Moon — humanity’s return to our nearest neighbor appears to be imminent.

And for good reason: A report on the “State of the Space Industrial Base” released in August predicted that China would overtake the United States “as the dominant global space power economically, diplomatically and militarily by 2045, if not earlier.” There are potentially trillions of dollars of resources on the Moon, on asteroids, and on other celestial bodies. As with space research and development in the past, there will be spinoffs that will improve life on Earth. And space is the next frontier in the long story of human exploration.

After a fifty-year delay, we may at last be on the verge of fulfilling this dream.

Artemis 1 blasted off from Kennedy Space Center on November 16, 2022, beginning its nearly month-long journey around the Moon. But before it lit up the night sky along Florida’s Space Coast, Artemis 1 was delayed again and again.

This first uncrewed test mission in the long-awaited human return to the Moon was finally on the pad and set to launch on August 29. First, there was an issue with engine 3. NASA fixed that. Then, on September 3, there was a hydrogen leak. NASA fixed that. Then there was Hurricane Ian. NASA couldn’t fix that, so the space agency rolled the massive Space Launch System rocket and Orion capsule back to the even larger Vehicle Assembly Building in Cape Canaveral. And so, we continued to wait.

Looking back at the history of NASA’s human space programs, the public doesn’t remember short-term delays like these. We remember the results, both triumphs and tragedies: Earthrise on Apollo 8, golf on the Moon on Apollo 14, Challenger exploding 73 seconds after liftoff. In the same way, we are not going to remember the delays of Artemis 1.

But we all know about the Long Delay: Since the Apollo 17 mission returned to Earth half a century ago, humanity has not once breached the confines of low-Earth orbit. The Long Delay is a collective cultural nostalgia, a yearning for the glory days of American spaceflight. It is a constant reminder of a glorious vision of the future from an ever-receding past. And it is a target of derision, cynicism, and regret.

It’s hard to date exactly when the Long Delay began. It may have started the moment the lunar module of Apollo 17 left the surface of the Moon in December 1972. It may have begun with President Nixon’s decision earlier that year to direct NASA to build the space shuttle, instead of telling the agency to sprint to Mars. Or maybe it began in 1970, when NASA canceled the planned Apollo 18, 19, and 20 missions. Perhaps it even began in July 1969, when Neil Armstrong stepped foot on the Moon and won the space race for Team USA, ending competition with the Soviets.

During the Long Delay, there have been many incredible developments in space. We’ve sent robotic probes across the solar system and beyond, capturing spectacular images and sending back critical data about Earth’s planetary neighbors. We developed a partially reusable space shuttle that built a permanently inhabited multinational space station, delivered the Hubble Space Telescope to orbit (and fixed it), and established a sense of normalcy around regular access to space. A nascent space private sector brought astronauts and satellite infrastructure into orbit. Our satellite network and GPS have enabled a whole host of technologies dependent on instantaneous communication and hyper-accurate location data.

And yet the Long Delay persists.

How did a country that went from absorbing the shock of Sputnik to planting a flag on the Moon in less than twelve years spend the next fifty struggling to get back there and living in the shadow of past glories? One crucial answer is that with every change of administration, new presidents have overhauled NASA’s human spaceflight program in response to shortcomings of their predecessor’s plans. Each change was disruptive and costly, both financially and technologically.

For a space program to be successful in the long run, consecutive presidential administrations must pursue a plan with achievable goals, and Congress must support the plan conceptually and financially. The lack of one or more of these prerequisites has doomed any ongoing American effort for human spaceflight beyond low-Earth orbit. The one exception to the space-policy whiplash has been President Biden, which is why the current Artemis mission is a unique development.

At first, we simply didn’t want to go back to the Moon. After Apollo, NASA shifted focus back to low-Earth orbit, building the Skylab space station. Several crews visited the station, but its orbit gradually decayed, meaning the station was moving closer to the Earth. NASA initially intended to boost Skylab’s orbit using the forthcoming space shuttle, but because of delays to the shuttle’s debut, the station couldn’t be saved. In 1979, Skylab re-entered Earth in a fireball over Australia and the Indian Ocean.

The space shuttle finally launched in 1981. Three years later, President Ronald Reagan called for a “permanently manned space station … within a decade,” what would eventually become the International Space Station (ISS). But costs ballooned and redesigns delayed construction, all of which was compounded by the Challenger disaster in 1986 that grounded the space shuttle that would deliver the space station to orbit.

In 1989, President George H. W. Bush announced his Space Exploration Initiative, which called for building the space station Freedom, but, more importantly, called for a permanent return to the Moon and then a mission to Mars. It was a compelling vision, but after NASA came back with an estimate of the plan’s cost — $500 billion — not only Congress but the White House too could not stomach spending that much money. The program was dead.

During Bill Clinton’s presidency, NASA focused on cost cutting and robotic missions under the slogan “faster, better, cheaper.” For human spaceflight, this meant abandoning plans for exploration beyond low-Earth orbit. NASA transformed the Freedom concept into the ISS, which the agency would build with the shuttle and operate with partner nations, including Russia.

By the end of the 1990s, the space shuttle still wasn’t even close to living up to what the program had promised. The shuttle was intended to replace many expendable launches and be a cost-effective “space transportation system” to get crew and cargo to orbit frequently and safely. Instead, the shuttle was expensive, did not launch frequently, and had known issues with safety.

After the Columbia disaster in 2003, which killed its crew of seven, it was clear that indefinite use of the shuttle was no longer a viable policy. President George W. Bush re-directed U.S. human spaceflight with his bold Vision for Space Exploration, which called for finishing the ISS and retiring the shuttle, returning to the Moon by 2020 and going to Mars. Once more, the president proposed a plan with clear objectives beyond low-Earth orbit. This time, Congress was on board, codifying the plan in the NASA Authorization Act of 2005.

But the program, called Constellation, faced delays and budget issues. By 2009, a government report found Constellation facing “significant technical and design challenges,” with “a poorly phased funding plan.” Although NASA administrator Michael Griffin called it “Apollo on steroids,” the budget wasn’t expanded accordingly.

President Barack Obama directed NASA to review the program, which was found to have “insufficient funds to develop the lunar lander and lunar surface systems until well into the 2030s, if ever.” Obama canceled the program, but Congress objected, resulting in NASA keeping remnants of Constellation, chiefly the Orion capsule, and pursuing a new heavy-lift rocket, now known as the Space Launch System (SLS). The program meandered without a vision. In 2013, Obama announced that we would now aim to send people to an asteroid by 2025 (after it was lassoed into lunar orbit). In 2016, he said that America would send humans to “orbit Mars” by the 2030s. The unnamed plan was still vague.

President Donald Trump changed the destination yet again, from an asteroid to the Moon once more. The program was later given a name, Artemis. Trump revived the National Space Council with the vice president as chair. In 2019, Vice President Mike Pence announced that the first lunar landing would be moved up to 2024 from the administration’s original estimate of 2028. In 2020, the United States drafted and signed the Artemis Accords, a set of multinational agreements designed to achieve broad global consensus on principles for space exploration.

In 2021, for the first time in decades, an incoming president did not overhaul his predecessor’s human spaceflight policy. Instead, President Joe Biden endorsed Trump’s Artemis program. Why? After all, Biden had been elected promising to undo many of his predecessor’s policies.

He may have started by analyzing trends. After a decade of relatively stagnant budgets from the mid-2000s to the mid-2010s, NASA finally began seeing increased funding. By 2020, NASA’s budget hit over $22 billion, and by 2022, under Biden, over $24 billion. Both of these budgets maintained high levels of funding for SLS and Orion. The various 2023 budgets being debated as this article went to press give NASA $25 to $26 billion, a healthy further increase. This trend line is a bipartisan vote of confidence in Artemis. With billions already spent, increased funding on the way, the first Moon landing moving up four years, and the first test mission so close, canceling Artemis would have been politically disastrous.

There’s also a new international competitor. China plans to build a base on the Moon, and although the threat of its ambitions in space was not required for our return to the Moon, it certainly has helped galvanize U.S. government interest and funding. And the Artemis Accords have expanded from eight to twenty-three nations since their inception, further cementing the program’s international presence and influence.

Constellation was an ambitious, expensive program that struggled to secure the funding it actually needed. Artemis is just as ambitious and just as expensive. But Artemis has achieved an alignment that no other presidential space policy has achieved since Apollo. The previous administration had put forth a vision with clear goals, and Congress had supported the plan conceptually and financially. Space policy whiplash is finally coming to an end.

The other development that has helped to bring the Long Delay to an end is the rise of the private space sector. After thirty years of regular access to space, the shuttle’s retirement in 2011 left NASA reliant on the Russians to get our astronauts to the ISS, requiring them to spend a total of $4 billion for seats on Russian spacecraft, an embarrassing sum for us to have handed over to our longstanding rival.

With NASA shifting focus to developing Orion and the SLS, the space agency turned to the private sector to provide transportation to low-Earth orbit. Both old and new space players received awards, including Boeing, the United Launch Alliance, SpaceX, Blue Origin, and Sierra Nevada. For the new players, NASA served as a source of critical early funding. The investments were risky, but they worked.

Ultimately, SpaceX and Boeing were chosen in 2014 to bring astronauts to orbit. SpaceX successfully developed and tested Crew Dragon, and it is now operational. Companies and governments everywhere are now clamoring for launch services aboard the Falcon 9, the SpaceX rocket that has become a safe, reliable, and cost-effective orbital transportation service. Boeing developed the Starliner crew capsule, and despite delays, finally had a successful test, and is aiming for its first crewed mission early in 2023. Though not selected for launching NASA astronauts, Blue Origin and Sierra Nevada continue to work on their programs. As the options for transportation to space are expanding in the private sector, the costs are coming down.

Artemis has three goals: returning to the Moon, establishing a long-term human presence there, and then heading to Mars.

The first goal, the Moon, will be accomplished over the first three missions. The uncrewed Artemis 1 in late 2022 tested both the SLS rocket and sending an Orion capsule into lunar orbit. Assuming current timelines do not slip, though they likely will, Artemis 2 will then send astronauts to lunar orbit in 2024, and Artemis 3 will land them on the lunar surface in 2025.

Why the Moon first, or at all? The Artemis program is Apollo-style in its presidential and congressional support but not in its purpose. Apollo was a key component of a Cold War–era strategy that prioritized landing on the Moon and beating the Soviets over any long-term scientific or economic rationale. In this sense, though aiming at the same place, Artemis is the opposite of Apollo — in Greek mythology, Artemis is Apollo’s twin sister and the two often held opposing viewpoints. The program is certainly driven by geopolitical factors, including competition with China, but is more focused on building a long-term, sustainable presence on the Moon that kickstarts a lunar economy and a new era of long-term scientific discovery. This is not a project we’ve already completed before.

The second goal of Artemis is constructing a space station in lunar orbit called the Gateway, which will serve as a “multi-purpose outpost” for future landings to the surface, missions to Mars and beyond, and for research and experiments in a unique environment. Astronauts headed to the Moon would arrive at the Gateway in an Orion capsule and transfer to a lunar lander to descend to the surface. The Gateway space station is essentially an astronaut layover in lunar orbit, and it is perhaps the most controversial element of the Artemis program. Critics have called it unnecessary and a waste of expensive SLS launches, slowing the program’s progress. Time-consuming and expensive construction of the Gateway will almost certainly cause cascading delays to missions beyond Artemis 3. It may be worth NASA revisiting the value of this project. NASA has also proposed a permanent “Artemis Base Camp” on the lunar south pole, complete with rover transport, though the agency is still determining the location for this outpost.

The third goal is a human mission to Mars at some point in the 2030s, after we return to the Moon. This will be enormously riskier and more expensive than reaching the Moon. A round-trip mission would likely last a few years. Life support systems would have to sustain astronauts millions of miles away from Earth with no recourse should something go wrong. These are not reasons not to pursue such a mission. But the levels of expense and risk are currently too high to head straight for Mars, without returning to the Moon first. Neither is there enough presidential and congressional alignment.

The elephant in the room, however, is SpaceX’s Starship, which, because of delays to Artemis, ended up competing with NASA’s SLS in a race to be the first to test a new launch system powerful enough to send humans to the Moon. SpaceX had hoped to launch Starship on an orbital test flight by December 2022, but that date has been pushed back to sometime in early 2023. SLS won that race, but regardless of what happens with Artemis, we are looking at a not-too-distant future with a private launch system that can perform the same functions as the SLS but at a fraction of the cost. A cost-effective heavy launcher could open the door to a whole host of other types of missions. Perhaps we could do an Apollo-style reach for Mars using Starship earlier than planned for SLS. Even before the Long Delay fully ends, NASA’s new rocket might already become obsolete.

The Long Delay of human spaceflight beyond low-Earth orbit may be almost over, but to make this end stick, NASA should implement several critical changes.

1. Fully switch from owning its own development and operations to purchasing launch services.

Purchasing launch services from the private sector is already how the agency fulfills crew transportation to low-Earth orbit. And that’s what must happen for deeper space after Artemis. The Space Launch System should be the final rocket ever built by NASA.

Each SLS launch costs $4 billion. Elon Musk has claimed that each Starship launch will eventually cost $2 million, though with the price for Falcon 9 launches currently sitting at $67 million, that number looks to be far from reality. But even if each Starship launch costs $200 million, the SLS would still look like a colossal waste of money. It doesn’t mean that once Starship is ready we should cancel the SLS immediately and shift to SpaceX. But it does mean that, moving forward, we should rely on the model that made the NASA–SpaceX partnership so successful. It is unclear how long the SLS will last. But whenever it ends, leaving the rocket development business entirely will be the logical next step for NASA.

We are already seeing early signs of a transition. NASA is moving away from producing the SLS rockets itself and toward purchasing SLS services from Deep Space Transport, a new joint venture between Boeing and Northrop Grumman. This would begin after the first few Artemis missions. The move may save NASA money, but also makes it possible for the rocket to be used outside Artemis.

2. Develop a space-specific version of In-Q-Tel or the Defense Innovation Unit.

In-Q-Tel is a nonprofit venture capital firm that invests in companies working on emerging technologies for the U.S. intelligence community. The Defense Innovation Unit was launched in 2015 to speed the development and use of emerging technologies in the military. The organization awards contracts in a process that takes just two or three months, rather than the year-and-a-half or more for traditional Defense Department contracts.

Whatever the structure, NASA’s focus should be more on funding external research and development, equipping and enabling the private sector with funding and technological breakthroughs to drive us further out into space and to allow NASA to purchase services, rather than owning the development itself. NASA also needs to emphasize competitive bidding, like it did when finally opening lunar lander development to a second company after selecting only SpaceX in 2021.

This move can happen over the next few decades.

3. Leave behind cost-plus contracts.

Cost-plus contracts, which the agency has long used to develop human spaceflight systems, are one of the main reasons it has always had trouble predicting its expenses. The type of contract pays a contractor all expenses plus an additional fee, guaranteeing a profit for the regardless of how many additional expenses are incurred. This in turn can incentivize larger expenses.

Criticism of these contracts has been mounting. In 2022, NASA Administrator Bill Nelson called them a “plague.” In 2017, Elon Musk said that to get NASA back on track, “You can’t do these cost-plus, sole-source contracts because then the incentive structure is all messed up” since contractors will “never want that gravy train to end.”

Instead, NASA must shift to fixed-price contracts, where a contractor receives an agreed-upon price regardless of final expenses. These have been used successfully for certain initiatives like the Artemis lunar lander, but the agency needs to embrace them more comprehensively.

4. Consider a rotational program to allow engineers and scientists temporary placement in the private sector, and vice versa.

Turning down a private-sector job with a much higher salary for a government position is a quandary that talented individuals in a broad array of tech industries face. Why not incentivize our space tech talent to try out working for NASA? The Rotational Program for Scientists, a pilot program beginning this year, is a great start for movement within NASA but should be broadened to opportunities outside the agency.

5. Consider separating the astronaut corps into an Earth unit and an interplanetary unit.

As the opportunities for private astronauts grow rapidly, especially in low-Earth orbit, the corps risks becoming obsolete. Over time, NASA could loosen some of the rules for access to the Earth unit by removing some of its requirements, like that astronauts have a master’s degree in a STEM field, while retaining the important physical fitness requirements. Alternatively, NASA could even privatize the corps, and instead of recruiting and maintaining its own astronauts, it could exclusively focus on research on space and the human body.

6. Hold a Shark Tank, but for rockets.

Finally, NASA could try something unorthodox: hosting a public competition — perhaps like Shark Tank — to invest in rocket technology that could one day power us to places like Europa. The space agency has an asset that few government agencies are blessed with: Space can captivate, inspire, and unify broad audiences across nations, ages, and political persuasions. Six hundred million people worldwide watched Neil Armstrong step onto the Moon. The incredible pictures from our space telescopes, first Hubble and now James Webb, awe us all. The launch of the first SpaceX Crew Dragon test, on May 30, 2020, was a ray of light a few months into the pandemic. Bring the public in, and not just for the results.

On December 19, 1972, the Apollo 17 spacecraft returned from the Moon and splashed down in the South Pacific, carrying astronauts Eugene Cernan, Harrison Schmitt, and Ronald Evans. Fifty years later, on November 16, 2022, Artemis 1 soared into space on its 25-day mission around the Moon, coming as close as sixty miles to the lunar surface before cruising to a distant lunar orbit, becoming the farthest-ever human-rated spacecraft from Earth.

In just a few years, there will be astronauts aboard the next Artemis mission to orbit the Moon, and then on the third mission we’ll be back on the surface. A new generation that never saw Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin walk on the Moon — or Cernan and Schmitt — will see new pioneers return.

As Artemis begins, the Long Delay ends. We may not be approaching Orbit City yet, but it’s time to watch some Jetsons reruns.

Exhausted by science and tech debates that go nowhere?