October 27, 2022

This article is a special preview of our Fall 2023 issue

Apple gets under your skin • Chicken McPetri • The downer about uppers • Bacon: tech skeptic? • Subscribe

It has now been fifty years since the oil crisis that began when Arab members of OPEC imposed an embargo on the United States. Announced on October 17, 1973, the ban on oil exports to America was an act of retaliation for our aid to Israel during the Yom Kippur War. The war itself had begun only days earlier when Egypt and Syria launched a surprise attack on Israel — the surprise attack on Israel by Hamas just days ago was apparently timed to coincide with the fiftieth anniversary of the 1973 war.

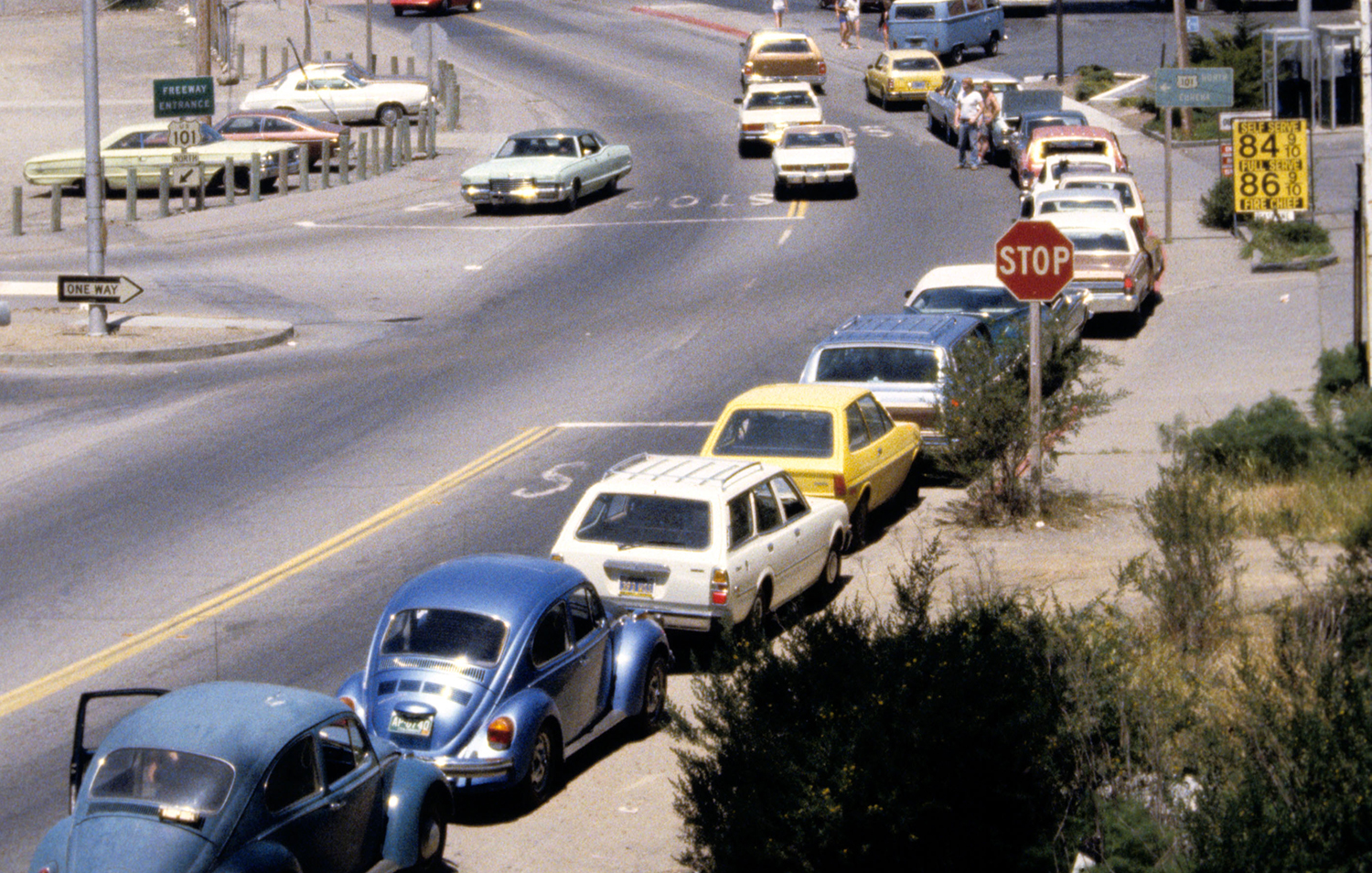

The embargo discombobulated Americans from the president down to the person on the street. The price of oil soared, there were lines at gas stations, and Americans feared that the use of oil as a geopolitical weapon would be repeated painfully for years.

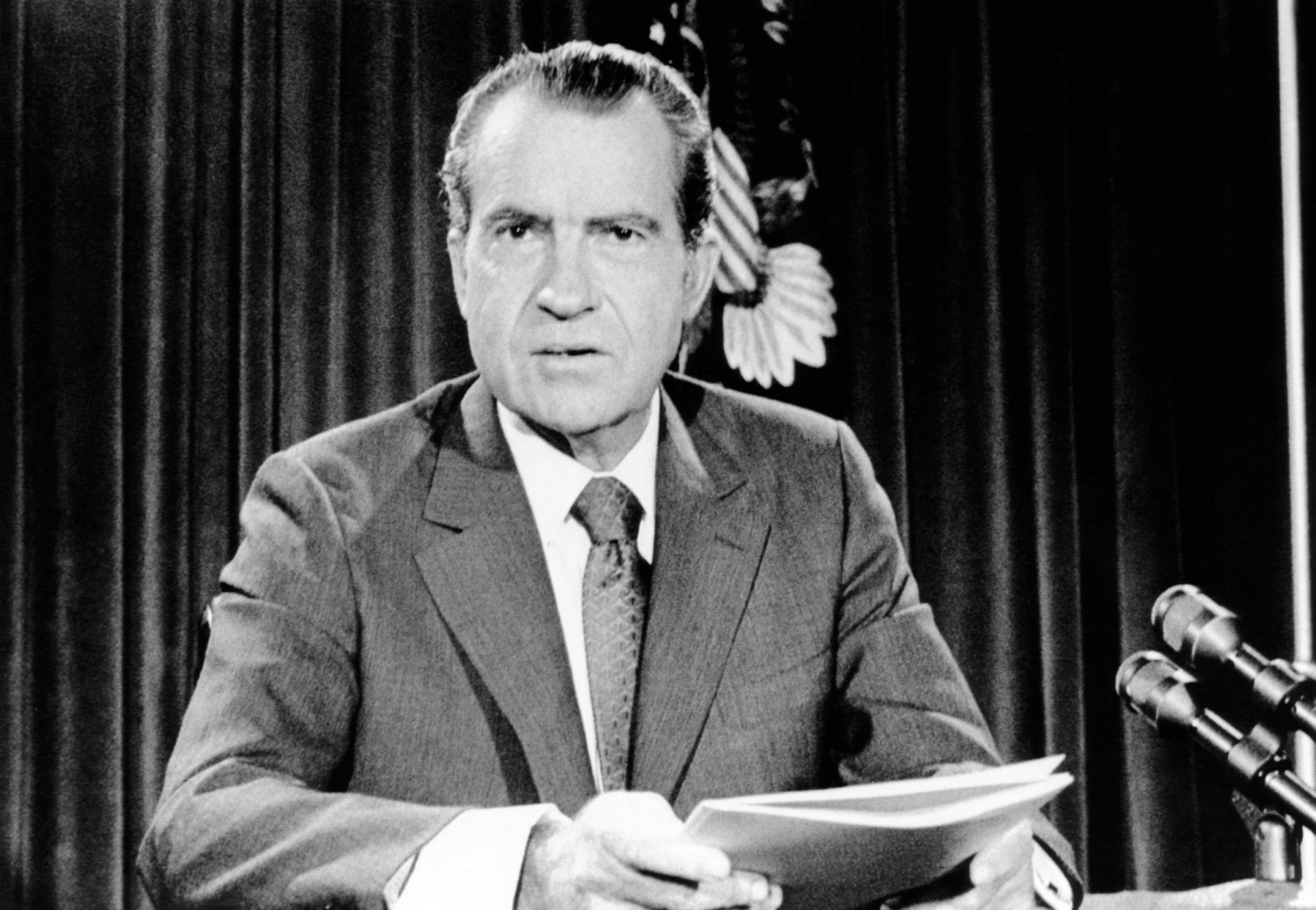

But the worst effect was on U.S. energy policy. Whereas the embargo lasted about five months, the toll on U.S. policy has lasted five decades and counting. The policy disaster began on November 7, 1973, three weeks after the embargo was announced, when President Richard Nixon went on television to announce America’s response, a grandiose program he called Project Independence:

Let us set as our national goal, in the spirit of Apollo, with the determination of the Manhattan Project, that by the end of this decade we will have developed the potential to meet our own energy needs without depending on any foreign energy sources.

Nixon’s project never went anywhere, because he was never clear not only about what it would cost or how it could be achieved, but even about what, exactly, “energy independence” meant: Would it apply to all energy, or really just oil? Would it mean having only the potential to meet our own needs, as he suggested initially, or actually doing so, as he claimed a few months later?

Yet despite the amorphousness of “energy independence,” it became the explicit goal of American energy policy thereafter. Every president since Nixon has advocated for it. But as Senator Barack Obama acknowledged in 2006, despite the rhetoric, “we have fallen short.” Then again, Obama left unclear whether his own call for energy independence was really the same as what we had heard before, suggesting instead that he had in mind “moving away from an oil economy,” a goal he reiterated in a 2011 speech as president. Most recently, presidential candidate Mike Pence promised in a campaign ad to “put our country back on a path to energy independence.”

In practice, the quest for energy independence has meant that America is continually seeking a “solution” to what we think of as the problem of participation in a global energy market. But if participation in this market is a problem at all, the cause is not external, as we have been led to believe ever since the embargo — it’s bad U.S. energy policies themselves.

On October 6, 1973, the armies of Egypt and Syria attacked Israel. Both armies made progress at first. But Israel, re-supplied with arms by the United States, quickly turned the tide.

The Organization of Arab Petroleum Exporting Countries (OAPEC), a subgroup of OPEC, declared the embargo eleven days after the initial attack. To increase the probability of the embargo’s success, OAPEC planned to reduce overall crude oil production by at least five percent each month until Israel withdrew, not just from territory recently won but from all territories gained in the Six-Day War of 1967 (the Third Arab–Israeli War).

Oil is fungible, however, and even with reduced production Arab exporters couldn’t prevent at least some of their oil from reaching the United States. The Nixon administration was expecting embargo-driven losses of between 10 and 17 percent of U.S. daily supply. But the embargo cut U.S. supply by only about 5 percent.

Nevertheless, in America there was chaos. There were shortages of gasoline around the country, which led to the famous gas lines, with motorists sometimes sitting for hours and being able to buy no more than five gallons. Fights broke out at service stations as people accused others of jumping the line. Many stations closed for a week or more at a time, and some closed permanently. People who used oil for heating feared freezing in the dark, while airline companies had to curtail flights. Citizens and industries blamed oil companies as well as Arabs for their plight, and they besieged the government with demands that it do something.

But what few understood was that the government had done something — something that caused the lines, the closed stations, the grounded airplanes, and instilled the fear of winter freezes without adequate heating.

In 1970, in a futile effort to stop rising inflation, Congress gave President Nixon the power to impose controls on wages and prices. At first, Nixon asked labor and business only to voluntarily restrain themselves, but inflation continued to rise. Under intense political pressure to stop this trend, Nixon turned to involuntary controls in the summer of 1971. Phase I of these controls imposed a general ninety-day freeze on wages and prices. After this period was up, Phase II empowered Nixon’s new Cost-of-Living Council (CLC) to decide whether any prices or wages should rise and by how much. In January 1973, Phase III began to walk controls back for most industries.

Not all industries, however. By the summer of 1973, Nixon announced new Phase IV controls for specific products, including oil and gasoline. If costs of crude oil rose, companies had to petition the CLC to increase the prices of heating oil and gasoline that customers would pay. The ceilings on oil and gasoline prices lasted in one form or another for the rest of the decade. Natural gas, which was price-controlled under a separate rule, was not freed completely from controls until 1989.

All this despite the fact that in 1970, the Chairman of Nixon’s Council of Economic Advisors, Paul McCracken, had observed that “it would be hard to think of a more effective way of creating a fuel crisis than to decree United States price ceilings … below those prevailing in the world market.” McCracken was stating a simple economic fact: If a price is fixed lower than what it would be in a free market, consumers will want more than suppliers can provide at that price — which results in a shortage.

Absent price controls, the embargo would have raised prices somewhat more, and more quickly, than they actually rose with price controls. But the process of price changes was slowed greatly by the ponderous CLC, which only approved price increases after costs had risen and applications were made. As station owners waited for the CLC to permit price increases so they could actually make a profit, they sometimes had to shut down for a time. Without controls, there would not have been any reason to shut down, and consumers could have bought gasoline if and when they needed it.

Of course, some said that because Arab oil producers were a cartel, there was no free market in oil anyway, so controls were necessary. But the fact remains that after the U.S. government fully lifted controls on oil prices in the early 1980s, prices fell. From this point forward — the Reagan years and onward — market turmoil produced price spikes but not the shortages, fear, and misery Americans experienced in the winter of 1973–74.

In response to the public outcry during the embargo, the president and Congress felt they had to do more to make the situation better. But in late November 1973, they made things worse. On top of existing price controls on oil and gas, Congress added quantity controls. Who received supplies of oil and oil products, and how much, would now be determined by the Federal Energy Office, a new entity created by Nixon and placed under the direction of the Deputy Secretary of the Treasury, William E. Simon.

Simon, reputed to be a “free market man,” was ironically cast in the role of central planner of the U.S. petroleum market. He did about as good a job as central planners in Soviet regimes were doing. In other words, he presided over a total mess. Government planners can never get supplies matched to demands because doing so would require knowing every market as well as the changing demands of every consumer. As a result, some gas stations, mostly in rural areas, got too much gasoline. Others did not get nearly enough and shortages became inevitable, particularly in cities where the gas lines were long.

Americans waited in lines for gasoline in the ‘70s not because of the embargo but because the U.S. government did not let market forces work. Although economists besides McCracken pointed this out — Milton Friedman was another — politicians were loath to blame themselves. There were much more visible bad guys: Arabs and oil companies were getting rich, seemingly at our expense, and appeared unconcerned at our discomfort. Blaming them was the popular choice.

The Arab members of OPEC began to wind down the embargo in January 1974 and officially ended it in March. Nevertheless, people continued to fret: the gas lines, the soaring prices, the shortages would be worse the next time the “oil weapon” was unleashed.

Yet from the Arab point of view the oil weapon was a dud. It failed to accomplish the most important goal, a change in U.S. policy toward Israel. Israel did not vacate lands captured in 1967 or 1973, and the U.S. government put no pressure on them to do so. American public opinion became even more strongly pro-Israel (or anti-Arab) after the embargo than it had been before.

Worse for OAPEC and its parent organization, although soaring prices filled their coffers for a while, they also helped plunge the world economy into a nasty recession and lowered demand and oil revenues in the months ahead. High prices also fueled exploration for oil outside of OPEC. By the 1980s, a great deal of oil had been found (though not then in the U.S.), and OPEC lost its pricing power for most of the next two decades.

Though the embargo was slowly coming to an end already in January 1974, that same month Nixon unveiled legislative steps to achieve his goals for Project Independence — for the U.S. to be completely self-sufficient in energy by 1980. If Congress had ratified all of Nixon’s proposals, the result would have been a little more production, a little more conservation. No one could have reasonably called it “energy independence.”

Members of Congress held idiosyncratic ideas about what energy independence meant. For example, Romano L. Mazzoli (D.-Ky.) argued that by looking to other energy resource providers and tightening our belts a bit, we could rid ourselves “of the ‘albatross’ of a dependency on Mid-East oil.” An internal report of the Federal Energy Office suggested a similar definition, calling for maximum resource development and a program of conservation that together would cut imports sufficiently so that the United States could replace oil from the Middle East with supplies from the West.

William E. Simon, for his part, believed that America would attain independence, of a sort, with a greater diversity of suppliers, so that no single source or coordinated group could set off the kind of confusion and bad judgment we experienced during the embargo. Diversity does not prevent embargoes, but it does greatly lessen their bad effects. Though Nixon’s administration never embraced Simon’s definition, the market eventually moved in that direction. By the 2000s, the United States purchased oil from over sixty different countries, and the largest supplier was Canada. Most importantly, in the 2000s America never experienced widespread shortages or gas lines, even though over half of the petroleum Americans consumed was imported.

President Nixon was succeeded by Gerald Ford in 1974, but the goal of energy independence remained. Ford tried twice to put Project Independence into effect. The first time, he pursued a conventional legislative path with the Energy Independence Act of 1975. The act included conservation measures, such as building winterization, standby authorities to deal with energy shortages, and a proposal to establish a national petroleum reserve. The bill did not pass, though the reserve was established by legislation passed later that year. Like Nixon’s original Project Independence, the Energy Independence Act could never have brought the United States full independence from foreign energy. Ford claimed that a strategic oil reserve would make America “invulnerable” to another embargo. How that would work he didn’t say.

The second time, Ford proposed to create an entity called the Energy Independence Authority, with an initial appropriation of $100 billion (roughly $600 billion today) to spend on energy-related projects. It was an unfocused plan and seemed destined to attract swarms of rent seekers. Congress rejected it without a vote.

By this time, it was increasingly obvious that if the goal of energy independence was complete U.S. self-sufficiency, then it was not feasible. As Vincent Ellis McKelvey, the head of the U.S. Geological Survey, quipped, independence could only be achieved “if Murphy’s Law is supplanted by a new law that states ‘whatever can go right, will.’”

Jimmy Carter, who regarded the world energy situation “as the moral equivalent of war,” became president in 1977. He also made two stabs at reaching some form of energy independence. First, he proposed the National Energy Act. Because he was a convinced neo-Malthusian who believed the United States was rapidly running out of oil and natural gas, Carter held that activist government energy policy was imperative for the survival of the American way of life. To that end, the policy prerequisite was a massive energy conservation commitment and also the development of alternative technologies, especially solar. “By the end of this century, I want our Nation to derive 20 percent of all the energy we use from the Sun,” Carter said in a speech.

Carter tried again to achieve major energy goals after the Islamic Revolution in Iran left its oil industry in shambles. By January 1979, Iran’s oil nearly vanished from the global market and prices soared.

Because price and quantity controls still applied in the United States at the time, gas lines returned and Americans again faced shortages. As citizens coped with another brutal energy crisis, a kind of national despair set in, deepened by projections of energy shortages and embargoes to come. Carter’s pollster, Pat Caddell, was struck by the pessimism of the American people and told Carter he needed to address that most of all.

With the price of oil climbing and OPEC in the ascendant, Carter proposed the Energy Security Act, which Congress passed in 1980. The administration called it a “virtually complete framework for a national energy policy” and touted it as practically magical in its answers to America’s problems. It wouldn’t just solve our energy problems; it would also tame inflation, correct America’s trade balance, create jobs, advance technology, preserve our standard of living, and restore America’s self-confidence. Unfortunately, magical thinking and practical failure have gone hand-in-hand with energy policy ever since.

The centerpiece of Carter’s framework was a technological silver bullet to solve America’s energy problem with America’s own resources. It took the form of an $88 billion program to replace more than two million barrels of imported crude oil per day by the early 1990s with a synthetic fuel substitute derived from coal, termed “synfuels.”

Synfuels embodied everything Carter previously sought to avoid. In 1977, Carter had said, “If we fail to act boldly today” — that is, pass his energy legislation — “then we will surely face a greater series of crises tomorrow — energy shortages, environmental damage, ever more massive government bureaucracy and regulations, and ill-considered, last-minute crash programs.”

That, in a nutshell, was synfuels: a crash program that posed technical, environmental, and managerial problems so great that Congress shuttered it only six years after its start.

Throughout the 1970s and since, there has never been a unanimous answer to what the goals of “energy independence” are. Freedom from embargoes? From oil? From the global energy market? The answers have often seemed vague, except among those who endorsed the goal of complete autarky. As Representative Owen Pickett (D.-Va.) put it seventeen years after the embargo, “It is time … for this Nation to adopt a declaration of energy independence from the rest of the world.”

A vast majority of the American people agreed with him — and still do. A 2017 Quinnipiac University Poll found that 92 percent of respondents answered the question: “How important is it to you that the United States produces all of its own energy and becomes energy independent?” with either “Very” or “Somewhat important.”

But in reality, it would not be beneficial for the United States to produce all of its own energy. In his 2008 book Gusher of Lies: The Dangerous Delusions of “Energy Independence,” Robert Bryce argues that that kind of energy independence is both technically impossible and a bad idea in every respect. He demolishes the purported benefits of complete separation from global energy markets and shows that many supposed benefits of autarky, such as defunding terrorism, are illusory. Terrorist funding, he explains, comes mainly from illegal activities — drug dealing, weapons trading, human trafficking — not so-called “petrodollars.” Even Osama bin Laden, Bryce points out, derived his wealth not from oil but from his family’s construction business.

Also, few officials have counted the costs of separation from world energy markets. A 1974 report from the National Academy of Engineering estimated that getting close to self-sufficiency would have cost up to $600 billion (close to $4 trillion today), which was roughly double the size of Nixon’s 1974 federal budget. Under Carter, the price tag would have been at least as high, and the probability of lasting success of any attempt just about zero.

Carter’s framework did include one important component: a phased ending of oil price controls. He had long opposed that step, but he changed his mind in 1978, convinced finally that it would raise the price of oil enough to encourage conservation.

Decontrol of oil was crucial to the long-term health of the U.S. economy, but ironically the outcome was the opposite of what Carter anticipated. The price of oil initially trended upward, and then began to sink. By the mid-1980s, under President Reagan, the price had collapsed. The synfuels program, which had been established on the expectation of ever-rising oil prices, was effectively terminated, as were many other Carter energy programs. OPEC, which most policymakers thought would soon own the world, verged on dissolution. While many OPEC economies tanked, the Western world thrived.

One might have expected that with the end of price controls and the growing penury of OPEC members, there would have been widespread agreement that shortages and gas lines were a thing of the past. But for the most part, policymakers, experts, and the general public were still reliving the Arab oil embargo. As I report in my 2013 book U.S. Energy Policy and the Pursuit of Failure, many policy experts in the early 1980s believed there was a high chance that the decade ahead would see another embargo and energy crisis. Then again, in the early ‘80s, the price of oil was still relatively high, and OPEC may still have seemed in control.

Yet even after the oil price collapse, supposed experts penned articles with titles like “Get Ready for Longer Gasoline Lines” and “Impending United States Energy Crisis.” A majority of Americans still envisioned more gas lines and energy crises ahead.

Congress too was still fighting against imagined embargo threats, gas lines, and inexorable price hikes. After Iraq invaded Kuwait in 1990, and prices of oil and gasoline spiked, Representative Jerry Lewis (R.-Calif.) opined, “If [the invasion] leads to gas lines in the country, that will create a revolution in each of our districts in terms of citizen attitudes.” Through the 2010s, U.S. dependence on foreign oil was frequently modified by the adjective “dangerous.”

Among policymakers, the goal set in the wake of the oil embargo of 1973, energy independence, has remained the goal ever since. Even today, polls show an overwhelming wish for energy independence among the public, even though there is no common understanding of what it means or has meant. Dozens of pieces of legislation during the last forty years have had “energy independence” in their titles or descriptions, and many have some ground-breaking new technology at their heart. But U.S. energy policy has not delivered either on independence or on breakthroughs.

President George W. Bush was first a fan of hydrogen-powered fuel cells for automobiles. In 2003, he announced a $1.2 billion initiative to have commercially viable fuel-cell cars by 2020. Though some are now available, commercial viability still seems a long way off.

Later, Bush supported legislation for mass production of cellulosic ethanol, which was the miracle fuel hyped in the 2007 Energy Independence and Security Act (EISA). Ethanol, which can imperfectly substitute for gasoline, has been mainly distilled from corn and other food crops. Bush had assured the country that immense amounts of ethanol distilled from cellulose-rich non-food crops and waste, such as switch grass and wood chips, would be ready in six years. Six has stretched to sixteen and little cellulosic ethanol has been produced in the United States, notwithstanding a tax credit of $1 for every gallon.

Despite the failure of cellulosic ethanol, EISA remains in force because it also included a mandate for 15 billion gallons annually of corn-derived ethanol. The vast subsidies involved in EISA would have brought out a phalanx of promoters and rent seekers in any case, but with corn (and the price of corn) at stake, EISA has been untouchable. Corn growers are an enormously strong constituency, so that despite messy bankruptcies of ethanol producers and questions about the environmental safety and technical efficacy of ethanol, there has been no serious effort to shut off EISA’s mandates.

By the 2000s, there was less of a concern about the return of gas lines; the focus was on the economic and political costs that OPEC could impose, especially on the United States. In other words, the enemy was pretty much the same as in the 1970s, and the response — energy independence — was too.

Prices of oil, gasoline, natural gas, and all associated products soared in the 2000s, with prices of both oil and natural gas reaching unprecedented highs. It was widely claimed that the United States and most other non-OPEC countries were about to run out of oil and gas, which would only raise prices higher. Congress fretted that OPEC would be bleeding us of all our money and destroying America’s way of life. In 2007, Representative John Peterson (R.-Pa.) worried that OPEC again dominated the world oil market, telling his colleagues, “Folks, we are in trouble.”

Unexpectedly, since the passage of EISA, the United States, through hydraulic fracturing, or “fracking,” has become a net exporter of natural gas, and it has reduced crude oil imports from its historic 2005 peak by 40 percent. Yet even as U.S. dependence on foreign suppliers dwindled, the dream of complete energy autarky survived.

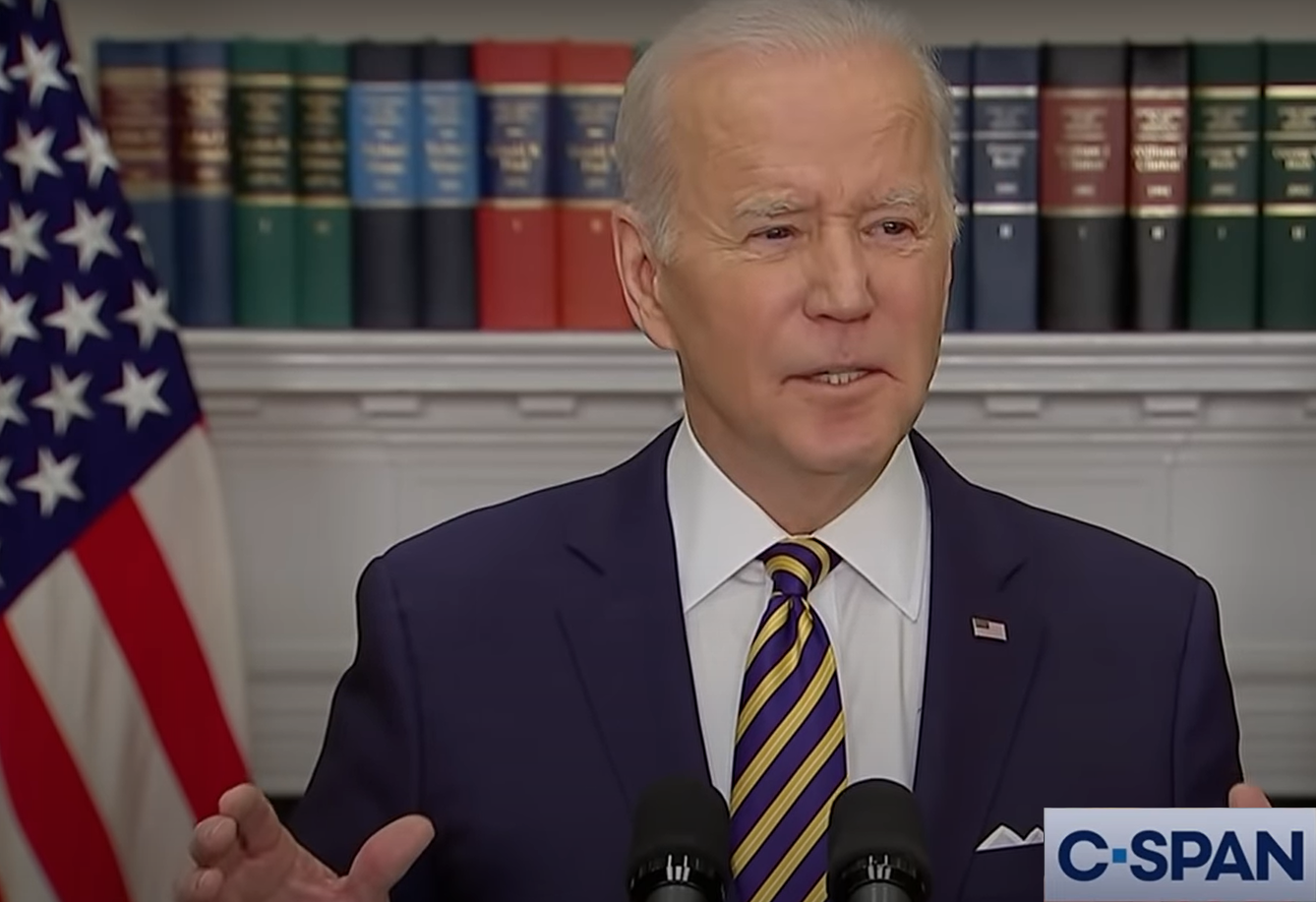

President Donald Trump claimed that with increased domestic production America had become energy independent after all; when Joe Biden took office, Republicans claimed that independence was soon lost. As Senator Ron Johnson (R.-Wis.) claimed in a July 2022 post on his website, “We finally achieved that energy independence … under the Trump administration. President Biden squandered [it] away.”

Several things here are incorrect, or at the very least misleading. Since 2019, we have indeed been producing more energy than we are consuming. And we are a net exporter not only of natural gas, but also coal and refined oil products. But this doesn’t apply to crude oil, OPEC’s main product: the United States is still a net importer of about 2 to 3 million barrels of crude oil per day. And although crude oil imports have increased under Biden, the United States remains a net exporter of energy overall.

It is worrisome, however, that the Biden administration has reverted to the kind of energy policies that have typically failed. As is evident in the 2024 Department of Energy budget, policies are being conceived on a monumental scale, aimed at transcendent outcomes that will not only achieve energy independence but will also solve climate change, provide millions of jobs, develop wondrous technologies, revitalize communities, and so on. As policymakers should have learned after the repeated failures of Carter’s grand framework, any energy policy intended to produce so many virtues is bound to fail. But there still is no sense that policymakers understand this.

So allow me to offer a few guidelines for an alternative, realistic energy policy. First, energy policy should be about energy, period. And second, it needs to be conceived modestly. The president, Congress, and the bureaucratic agencies need to set goals that are achievable. And the goals need to be designed to solve a set of problems that exist now, not ones that are thought to be still with us from fifty years ago, like energy independence, or ones that have a long-term uncertain future. For example, the U.S. government seems hell-bent on a grandiose plan: an “energy transition” to an economy that will run almost entirely on renewably generated electricity. But the costs and time scale of this vast transformation are both confused and troubling.

The simple truth is that energy markets have worked fairly well for many decades. Look at the example of natural gas: The gas industry endured price controls, and a slew of other controls, from the 1930s to 1989. In 1977, John F. O’Leary, appointed to be deputy secretary in the newly created Department of Energy, said that U.S. natural gas “has had it.” But, fortunately, some people in the industry disagreed. After price controls and other regulations were finally removed, natural gas production boomed. To a large extent, government energy policy has hindered, not helped, our domestic energy sector. Picking technological winners, selective environmental enforcement, subsidies to favored industries — a lot can be cast aside.

The value of energy interdependence has become clear. Total autarky, though seemingly comforting — let’s worry only about ourselves — was and is a terrible idea. If we are cut off from all other nations, who do we ask for help and how do we receive it, when hurricanes close our refineries, or a technical problem or human error makes a pipeline unusable? Only through energy interdependence, letting international markets work, will America continue to thrive.

Nevertheless, there do seem to be some areas where government has a role to play. An obvious one now is to make the national electric grid — and our national energy infrastructure broadly — more resilient to weather, cyberattacks, and other threats.

This is an important but relatively modest goal. Modest programs go against the American love of the spectacular, but they are a necessary approach in a vital area of policy that has had a history of devising magnificent plans that are impossible to carry out.

Meanwhile, the traumatic effects of the 1973 Arab oil embargo linger. In a 2015 Congressional debate about energy independence, U.S. oil exports, and the Middle East, then-Representative Kevin Cramer (R.-N.D.) reminded his colleagues of the embargo, which, he said, “led to the very issue we are talking about today…. Let’s not, I would say, let history repeat itself.”

It is long past time for policymakers to stop the effort to solve the embargo through the elusive quest for energy independence. The embargo story is unlikely to repeat, but it has scarred energy policy for fifty years, and it still haunts our dreams.

Editor’s note: The opening paragraph of this article has been updated from the print edition to mention the recent attack by Hamas on Israel.

October 27, 2022

April 26, 2016

Exhausted by science and tech debates that go nowhere?