Scientific knowledge achieved through years of research, and accepted as true by experts, is rejected by President Trump. It’s rejected by his cabinet. And it’s rejected with the apparent support of a majority of Congress and a majority of voters. Climate change is nothing at all to worry about, vaccines, on the other hand, cause autism, and draconian tariffs are actually good for the economy. But rejection of settled scientific truths is not enough for the president. With government funding on the chopping block for efforts ranging from space science and cancer research to weather prediction and the training of future scientists, Trump is also mounting a historically unprecedented attack on the scientific institutions tasked with discovering the future truths upon which human progress depends.

So it’s easy enough to believe that Trump and his supporters are irrational and out of touch with reality. But another interpretation is that the nature of truth itself is complicated in ways that the president has benefited from and his political opponents have failed to understand.

Really? Isn’t truth fixed by reality itself, untouched by our politics? Science establishes those truths and, as Galileo explained, “the judgment of man has nothing to do with them.” Truths would be true even if people didn’t exist.

During the current political chaos, the idea that accepted notions of truth are up for grabs may be difficult to consider dispassionately, especially for those who are shocked and frightened by Trump’s return to power. To put today’s battles over science and truth into perspective, a historical example, from a differently troubled time, may help. We can start with a pure truth of the Galilean sort, the one equation almost everyone knows: E=mc2. Einstein’s famous formula, which says that small amounts of mass can be converted into enormous amounts of energy, described the truth that allowed scientists and engineers to build the two atomic bombs the United States dropped on Japan in August 1945 to end World War II.

By 1958, eight thousand or so more such weapons had been built by the Americans and the Soviets, sufficient to immolate us all. In February of that year, two illustrious scientists, Linus Pauling and Edward Teller, debated on national television whether testing of these weapons should continue. Pauling was a Nobel-winning chemist and ardent pacifist. He had already gotten nine thousand scientists to sign his petition to end all nuclear weapons tests. In arguing for a test ban as a step toward international disarmament, Pauling cited scientific evidence that the radioactive fallout from a single hydrogen bomb test would lead to birth defects in 15,000 children worldwide. Teller, Hungarian-born and a renowned physicist, had fled Nazi Germany in 1933, and contributed to the U.S. development of the hydrogen bomb. In his judgment, the dangers to human health from atmospheric testing of nuclear weapons had “not been proved, to the best of my knowledge, by any kind of decent and clear statistics.” Drawing on the lessons of World War II, he argued that countering the threat of the Soviet Union demanded an active U.S. weapons testing program.

As Melinda Gormley and Melissae Fellet observed in a 2015 article about the debate, neither scientist tried to portray himself as objective about the matter; neither claimed that the scientific facts as he understood them were independent from his beliefs about how best to pursue peace. And so the debate’s moderator summed things up in a way that today might seem strange: “It is apparent that the issue has not been resolved. I’m sure both our guests would agree that its ultimate solution rests in our hands … that each of us bears the moral obligation to examine the evidence, draw conclusions from this evidence, and act upon our convictions.” Disagreement between scientific experts about how to deal with the risks created by nuclear weapons would have to be resolved democratically.

In the decades following the Pauling–Teller debate, scientific research aimed at informing public policy expanded enormously to help meet the risks and challenges of a rapidly modernizing world. This was a new task for science. Billions of dollars funded thousands of scientists to study questions as disparate as: How safe is nuclear energy? Which pesticides and food additives cause cancer? What are the causes and impacts of acid rain? When should women start to get mammograms? Are genetically modified foods necessary to feed the world? What are the economic benefits of environmental protection? Does standardized testing improve educational outcomes?

Research programs motivated by such questions were supposed to reduce uncertainties to arrive at the truth of the matter. Agreement on actions to solve the problems was supposed to follow. But in very few cases did this happen. Calculations of, say, the risk of a nuclear reactor meltdown, or a low-dose toxic chemical exposure, or a future pandemic required that scientists make heroic assumptions about incredibly complex phenomena — a direct invitation to contradiction by calculations made by other scientists making different assumptions. Uncertainties around these and similar questions did not get reduced; they expanded. And disagreement about what to do persisted, and often got worse.

Separating science from politics under these conditions was impossible. In 1983, the Nobel-winning social scientist Herbert Simon assessed the situation and came to the same conclusion as the moderator of the Pauling–Teller debate: “When an issue becomes highly controversial,” Simon wrote in Reason in Human Affairs, “we find that there are experts for the affirmative and experts for the negative. We cannot settle such issues by turning them over to particular groups of experts. At best, we may convert the controversy into an adversary proceeding in which we, the laymen, listen to the experts but have to judge between them.”

It was sound advice. “Adversary proceedings” are at the heart of democratic institutions, and since the 1960s science’s role in them has been expanding. At Congressional hearings, Democrats often call on one set of scientists and Republicans on another to provide competing facts and support contradictory policy preferences. A main task of the legal system is to adjudicate between competing claims about what is true in the world, and in fact many of the intractable debates that would seem to hinge on scientific evidence — from choosing a nuclear waste site to determining if a chemical really causes cancer in humans — have been argued in courts. Meanwhile, responsible media coverage about such conflicts includes quotes and facts from experts pro and con, so anyone can decide which evidence and experts comport best with their own values and beliefs.

Politically controversial issues are never settled by Galilean, E=mc2 truths. Instead, truths are continually negotiated through the institutions of democracy. Scientists — “experts for the affirmative and experts for the negative” — are participants in the negotiation process, but often it is judges, juries, lawyers, elected officials, bureaucrats, advocates, journalists, and voters who determine what counts as truth.

Through the second half of the twentieth century, as this interweaving of science and democracy expanded, public confidence in science and scientists remained very strong. The American people and their politicians seemed satisfied that the institutions of science and democracy were working together reasonably well. Presidents of both parties oversaw and supported increasing federal investments in science.

Starting in the early 1990s, concerns about climate change began to shift the partisan landscape for science, and for truth.

Congress began addressing the risks of climate change in its usual way, pouring billions of dollars each year into scientific research with the promise that uncertainties would be reduced and agreement on action would result. And most experts agreed about the basic science linking greenhouse gas emissions to slow, albeit uneven, increases in atmospheric temperature during the twentieth century.

But agreement on the fundamental science did not determine what to do about climate change any more than E=mc2 had determined what to do about nuclear arms. Policymakers would need to know how quickly climate change would unfold, how severe the consequences would be, how those consequences would be distributed, how much it would cost to reduce them, and what were the best alternatives for doing so. These were the same sorts of open-ended, only half-scientific questions that had been fueling political disagreement around other types of risks for fifty years.

In the 1990s, Democrats aligned themselves with a policy agenda that called for U.N.-led governance of greenhouse gas emissions, artificial markets to set a price on these emissions, and regulations and incentives to stimulate public choices aimed at reducing them. Here was an agenda that Republicans were bound to hate. So of course they were skeptical about the science that, despite all the uncertainties, supposedly dictated what had to be done. Research on public attitudes about climate change showed that one’s level of concern about the problem was largely a reflection of one’s ideological views — not one’s level of science literacy. (If that seems surprising, just remember Pauling and Teller.)

Driven especially by Vice President and 2000 presidential candidate Al Gore’s concerns about climate change, Democrats at the highest level began branding themselves as the party of science, rationality, and truth. Science had become a wedge issue. When Gore lost to George W. Bush in 2000, attacking Bush for being anti-science immediately became a staple of Democratic opposition strategy. When John Kerry ran against Bush in 2004, he promised, “I will listen to the advice of our scientists so I can make the best decisions…. This is your future, and I will let science guide us, not ideology.” He lost, too. After Barack Obama won in 2008, he proclaimed in his inauguration speech that he would “restore science to its rightful place” in American society.

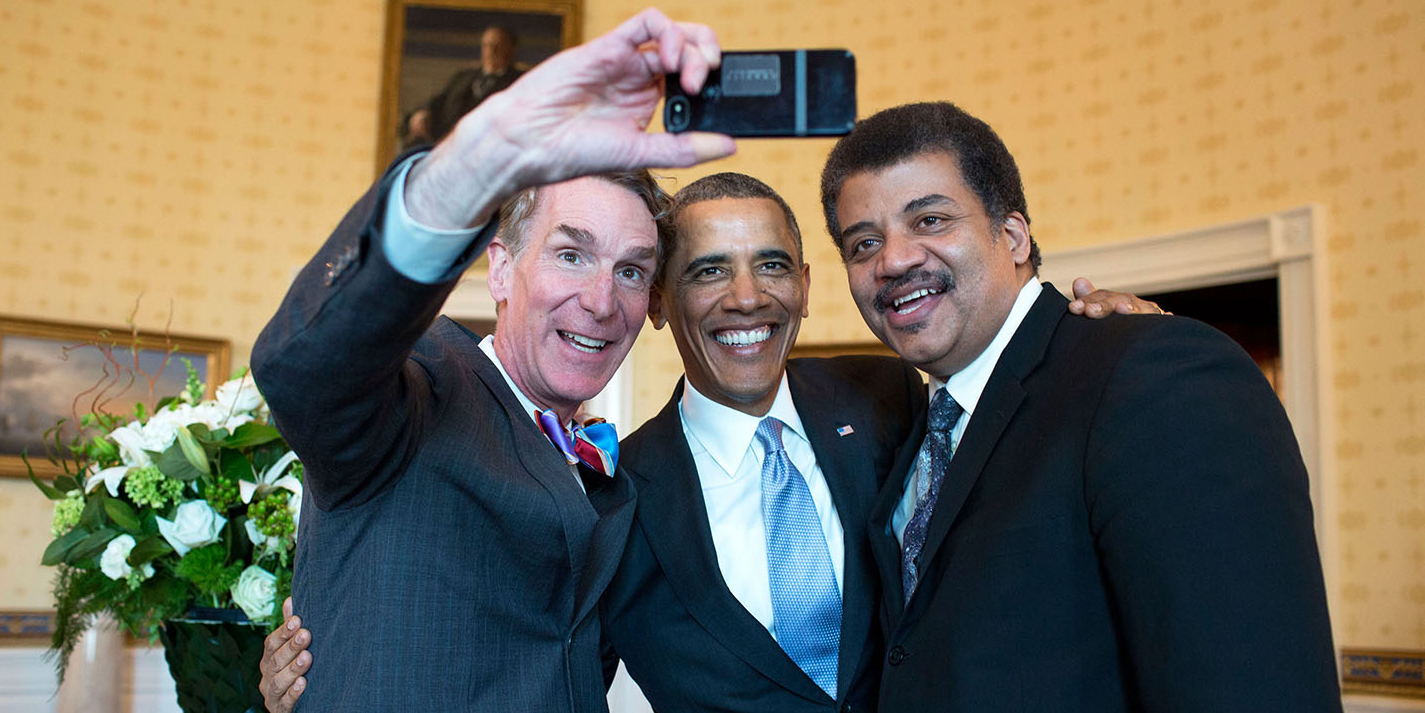

The scientific community, to the extent such a thing exists, embraced the alliance with the Democrats. Shortly after Obama took office, the weekly editorial in Science magazine declared: “The Enlightenment Returns.” In 2012, a letter from 68 Nobel-winning scientists supporting Obama’s re-election stated — almost certainly incorrectly — that his Republican opponent, Mitt Romney, would “devastate a long tradition of support for public research and investment in science.” The letter said nothing about the political affiliation of the signatories, as if that were an irrelevance, but, writing for Nature magazine at the time, I found that of 43 who had made political donations, only five had ever contributed to a Republican candidate. In 2014, the American Association for the Advancement of Science appointed as its director a former Democratic member of Congress with a Ph.D. in physics. As I wrote at the time, “The more the AAAS, and so the science community, is seen to line up behind one party, the less claim it will have to special status in informing difficult political and social decisions.” In 2014, a PAC was created to support Democratic candidates who were also scientists. American science increasingly looked like a Democratic interest group.

The stage was set for what happened during Covid. As the pandemic began to spread, the best ways to protect people from the disease were highly uncertain. Choices and beliefs about wearing masks, social distancing, school and business closures, and even appropriate medical interventions mapped right onto pre-existing political fissures in American society about freedom versus safety, and about the authority of government and of science itself to dictate our behavior. Leaders of the mainstream scientific community, rather than owning up to both the uncertainties and the value judgments behind policy choices, tried to invoke their status as purveyors of Galilean truths to explain why, say, six feet was the right amount of social distancing, or why school closings needed to persist.

Large swaths of the country, including many scientists and doctors, were unconvinced, but dissent was portrayed by Democratic and scientific leaders as politically motivated and anti-scientific. President Trump exploited these conditions to sow further division and distrust across society. The new Covid vaccine had its Galilean truth moment and about two-thirds of Americans chose to get at least two vaccinations — but as the pandemic began to wane, and vaccine efficacy along with it, politics infected that domain as well.

Seventy years of growing entanglement between science and politics show that the truths that matter most in democratic decision-making emerge from the political arena, not the laboratory. When Democrats sell themselves as the party of science, truth, and rationality, what they are really saying is that if you are rational and believe in science and truth then obviously you will support Democratic policies. But given that half the country does not ideologically align itself with Democrats, this is a hard case to make, and those who disagree with Democratic agendas may in turn wonder why they should accept the science those agendas bring with them. Such skepticism may not be irrational, or even anti-science. Yet it has created a space not just for Trump’s endless effusion of lies, but for the attacks he and his minions are mounting on mainstream scientific knowledge and on the scientific institutions that Democrats had labeled as their own.

If the Democratic Party wants to convince more voters that it is the party of what is true, it will first have to convince them that it is the party of what is good, what matters, and what is right.

Exhausted by science and tech debates that go nowhere?