We have all heard stories of people pilloried online. One of the earliest instances occurred in South Korea in 2005, when a young woman’s dog pooped in a subway car and she didn’t clean it up. Someone had taken photographs with a flip phone and posted them online, unleashing nationwide public harassment. The most famous story from Twitter is that of communications director Justine Sacco, who in 2013, before a flight to South Africa, tweeted a hamfisted joke about getting AIDS. Even though she had only 170 Twitter followers, the post blew up — as did her life.

The two stories show rather different kinds and levels of offense and shaming. But they both illustrate the same reality. Once upon a time, an ill-advised comment or action drew an appropriately stern rebuke from a friend or a boss or a stranger; today it draws a public firestorm that can ruin you. So now everyone is on guard, because everyone is watching.

Government eavesdropping and corporate data harvesting are worrisome, but what most of us really fear, even if we don’t think much about it, is the public eye. That is Jeremy Weissman’s argument in The Crowdsourced Panopticon: Conformity and Control on Social Media. Weissman, an assistant professor of philosophy at Nova Southeastern University in Florida, contends that ubiquitous cameras transmitting over the Internet at viral speed create a peer-to-peer surveillance network. The book paints a deeply unsettling picture: Online carrots (“likes”) and sticks (mockery), and the threat of full-blown cancellation, foster mass conformity.

Weissman’s point is not that online shaming itself is always inappropriate but that we have come to fear it for all manner of actions. While the medieval stocks were meant to deter a narrow range of sins, the online pillory clamps down on deviance of all kinds.

As we seek to earn retweets and avoid ire, we risk becoming a “personality machine,” Weissman writes, “emptied out and programmed by society, watching oneself do as society signals one to do.” We “judge ourselves based on how others judge us on the screen, and act out the desired roles as directed accordingly.” The near ubiquity of screens means that there is no longer a “backstage” to daily life, a place where we can be ourselves. We are stuck always performing.

Neil Postman said about television that its real threat lay in it becoming the “background radiation of the social and intellectual universe.” Today, the willingness of Americans to “cancel” relationships even with their friends and kin because of political differences or beliefs about Covid portends the advancing reach of social media’s radiation. But while The Crowdsourced Panopticon offers a powerful indictment of our culture’s toxic exposure, the book’s focus on technocratic fixes for conformism misses what’s really at stake in online shaming, showing how hard it will be to escape the digital pillory.

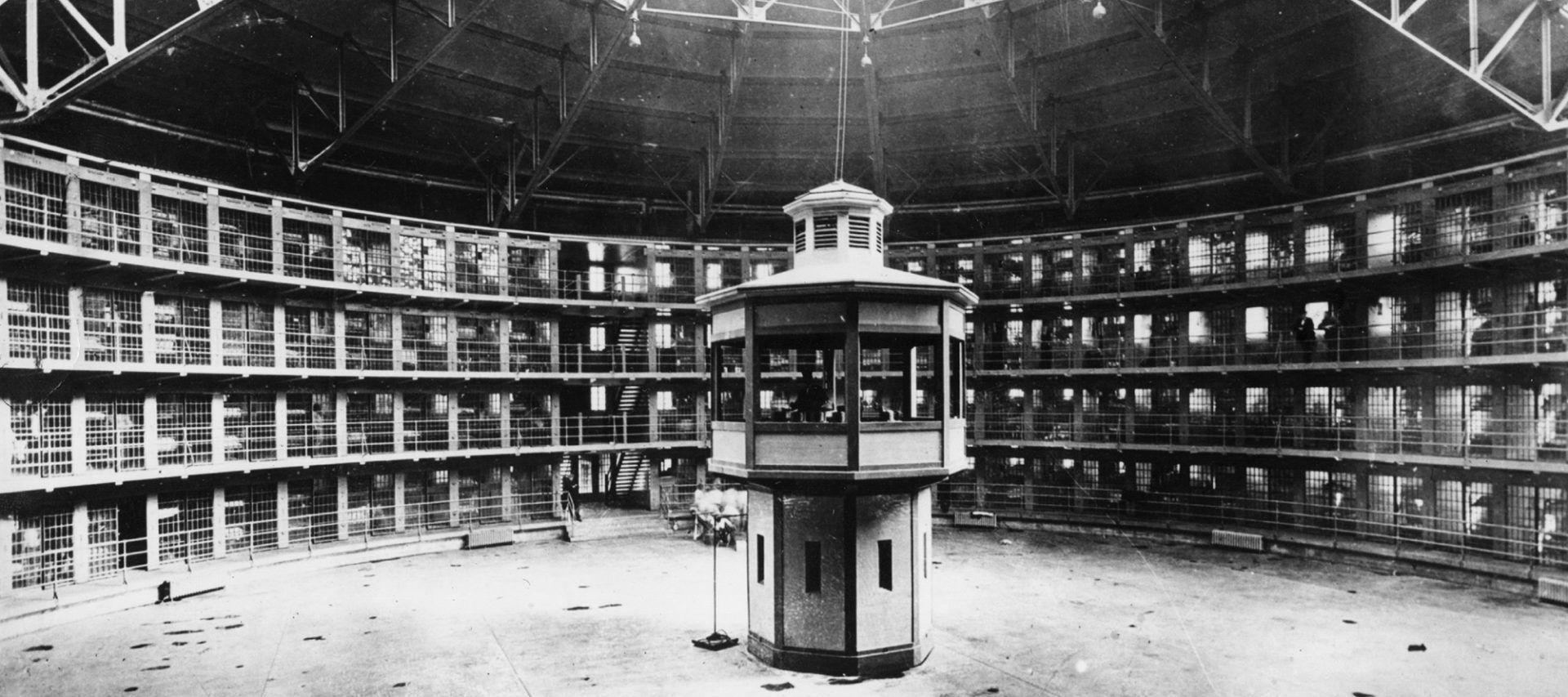

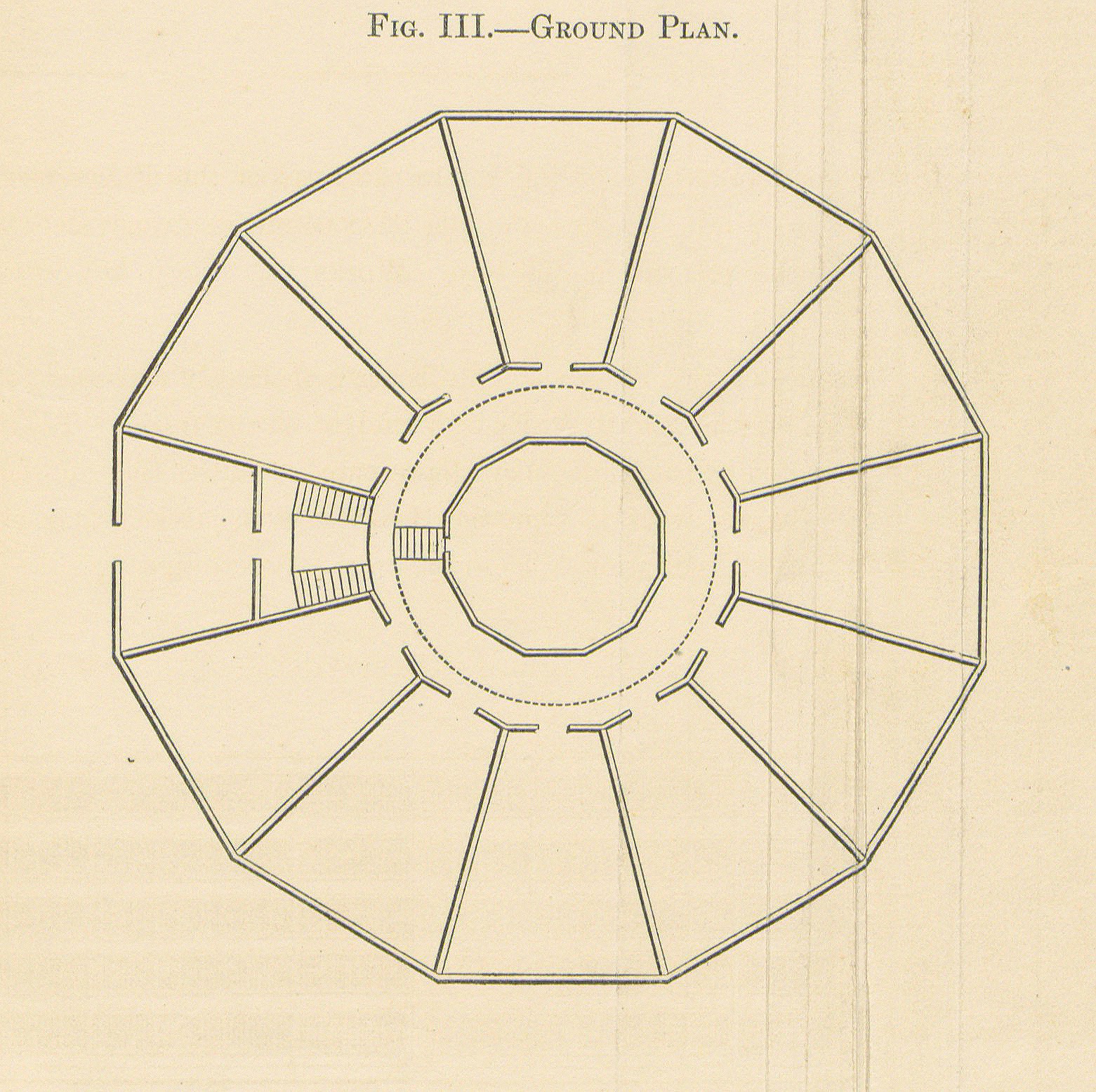

The title of Weissman’s book refers to the concept of the panopticon pioneered by Jeremy Bentham in the eighteenth century, when he imagined a prison as a circular building in which a central guard observes the jail cells surrounding him. Bentham argued that such a design would rationalize the disciplining of prisoners through its radical transparency. Because they could be observed at any moment, whether or not they actually were, prisoners would be constantly on guard. They would come to police themselves out of fear of punishment should their deviance be observed. As George Orwell described Big Brother’s television screens in 1984, “You had to live — did live, from habit that became instinct — in the assumption that every sound you made was overheard, and, except in darkness, every movement scrutinized.”

French philosopher Michel Foucault extended the use of the panopticon idea to think of it as a metaphor for the exercise of modern political power broadly. In his 1975 book Discipline and Punish, Foucault wrote:

The Panopticon must not be understood as a dream building: it is the diagram of a mechanism of power reduced to its ideal form; … it is in fact a figure of political technology that may and must be detached from any specific use.

But metaphors can both illuminate and obscure. Scholars have conceptualized as “panoptic” everything from parents texting to check up on their adult children to walkable neighborhoods. Extended so far, the panopticon becomes a synonym for almost any and all social pressures on individuals to behave in line with prevailing norms, something that cultures and societies cannot exist without.

Weissman is careful to demonstrate that the crowdsourced panopticon he describes is not an exaggerated metaphor. Real people are really watching all the time. And there is no practical limit to the number of people who could be watched by this peer-to-peer surveillance system, for there are citizens with smartphone cameras and broadband connections nearly everywhere. “Smart glasses” from Ray-Ban and other companies threaten to make cameras that are practically invisible ubiquitous. The data is stored online, almost never disappears, and is easily searchable. Information crosses the globe in the blink of an eye. The Stasi and KGB could only have dreamed of such a system.

Technologists champion a society built upon such radical transparency, or at least believe it to be an inevitability. Weissman notes how Wired’s advice column “Mr. Know-It-All” exhorted readers to “Shoot video first, ask questions later”:

I believe documenting any altercations you witness is a moral good. We need to be watchful, to protect one another. We need to keep our cameras up, arrayed in a kind of crowdsourced Panopticon.

Safety becomes inseparable from surveillance, even if the column asks readers to think carefully about the benefits and harms of posting the video. Former Google CEO Eric Schmidt dreams of a world where “everything is available, knowable, and recorded by everyone all the time,” while Airbnb founder Brian Chesky believes that a digitally enabled “reputation economy” will allow for “so many different activities that we can’t even imagine right now.” A radically transparent society also conveniently aligns with Silicon Valley’s dominant business model.

Is Weissman exaggerating the threat? Would the risk to our mental lives look less dire if we each spent just a little less time online? The hope feels vain. Weissman notes two websites — Lulu (thankfully short-lived) and Peeple — that are like Yelp for human beings, letting users rate others publicly. A 2015 Washington Post piece offered a sobering assessment: “You can’t opt out…. Imagine every interaction you’ve ever had suddenly open to the scrutiny of the Internet public.”

Weissman’s biggest worry is that in this panoptic environment we will cease to make passionate commitments. Instead we surrender ourselves to the online public and conform to the opinions of the crowd.

Weissman’s analysis of what he calls the “net of normalization” is rich, helping to show the immense social pressure to conform. But conformism itself is a flawed and at best partial explanation for why we shame others.

As has become cliché in analyses of digital-age pathologies, Weissman draws an analogy between smartphone-connected humans and rats in a Skinner box. We compulsively aim for shots of dopamine via “likes” and followers, while attempting to assuage our fear of missing out:

So in addition to the positive reinforcement of trying to please the crowd there is the negative reinforcement of trying to avoid being shamed and rejected, to participate, but to make sure to do so in a way that pleases the group, so that we feel like we belong.

This may explain why we conform to the crowd. But does shaming non-conformers actually serve the same functions? Is it just another compulsive act to please the crowd, of enforcing conformity and thus a collective sense of belonging?

If Twitter is a Skinner box, and our need to belong explains why we keep pulling levers to conform and to cast out sinners, then why do 90 percent of U.S. Twitter users create only 20 percent of the tweets, as a Pew survey found? One wonders how exactly all these lurkers would be so behaviorally conditioned, even if that picture were accurate for the “extremely online.”

We might make better sense of habitual lurkers and their participation in dog-piling by looking to the dystopian TV series Black Mirror. In the episode “The Entire History of You,” the show imagines an implant called a “grain” that records and can replay everything one has heard and seen. Collectively, it creates a kind of panopticon, where people have photographic memory of everything you have said and done. The protagonist Liam struggles to resist the temptations of his implant, using it to endlessly scrutinize the world around him, as when he torments his wife with jealousy-fueled analyses of her behavior at a party. He is obsessed — to the point of self-ruin — with trying to reveal her unfaithfulness. In this view, online shaming may be less about enforcing conformity, or pleasing the crowd, than catching others in the act in order to confirm our worst suspicions about how bad they “really are.”

The book’s focus on conformism overly shortens its reach in other ways. Weissman worries that original artists of the past would not have emerged in today’s radically transparent world. Would eccentrics like James Hampton, who meticulously created intricate religious art out of scavenged materials, or innovative bands like The Ramones emerge today?

That’s a worthy question, but by focusing on artistic expression Weissman sidesteps the thornier issues surrounding “cancel culture,” where public discussion centers on whether online shaming is just, whether some kind of conformity is a social and moral good. Actor LeVar Burton echoed a widespread Twitter talking point when in a recent interview he stated that cancel culture was “misnamed,” arguing instead that we have a “consequence culture” that now is “finally encompassing everybody.”

In this view, online shaming may be justified for cases like Maya Forstater, who tweeted about her belief that biological sex is unchangeable, or for the “Central Park Karen,” who called the police on a black birdwatcher after an argument over her unleashed dog. “Cancellation,” some would say, demonstrates that grave social ills no longer go unpunished. A similar logic is used to justify doxing people who violate Covid rules. In other words, for advocates of “consequence culture,” online shaming is less about clicks than it is about helping to establish a just society. But we ought to be able to ask whether or when or to what extent the use of the digital pillory itself is just. Weissman’s focus on conformism obscures that whole question.

What about the broader effects of “cancellations” on political speech? Anne Applebaum reports in the Atlantic on the growth of an “illiberal bureaucracy” that increasingly forces professors and journalists to resign or subjects them to months-long investigations for breaking new social norms. A recent Cato survey found that 62 percent of Americans say they have political opinions they are afraid to share.

Some will claim again that it’s these views that are illiberal and that conformism in these cases is a social good, that it makes the uttering of minority opinions on racial or gender issues taboo. But just because divergent views have become less visible doesn’t mean they are becoming more rare. And intolerance of divergent views could foster more extreme positions, as it encourages dissenters to see themselves as an embattled group.

A further underexamined question is whether “consequence culture” is in fact politically consequential. The people who suffer most from public shaming are typically not cultural or political leaders but middling members of the professional class, whose sins involve tweeting a poorly thought-out joke, or, as in the case of political data analyst David Shor, simply sharing a study out of sync with the dominant moral narrative.

The consequences of cancellation are disproportionate, violating even retributive theories of justice. Some judge the psychological sting of shame and ostracism as even more hurtful than physical pain. Weissman cites an 1899 article about prisoners who said they preferred three months in prison to one hour on the pillory. Online shaming has left its victims often not just unemployed but traumatized and even suicidal. A New Yorker piece last year told the story of a Polish doctor accused of violating social distancing protocols while waiting for the results of a Covid test, which turned out to be positive. He became so overwhelmed by online vitriol and late-night threatening phone calls that he eventually took his own life. Digital shaming is not really about retribution. It is driven by a desire to symbolically purify the public sphere, giving citizens the feeling of political efficacy, the potentially illusory belief that justice has been served.

In a 2019 paper, the sociologist Musa al-Gharbi suggests that online dogpiling in the name of racial tolerance may be merely “performative antiracism,” a kind of bizarro noblesse oblige where upper-class whites signal their identitarian enlightenment. It is an attempt to compensate for their privilege and convince themselves and others that they are one of the good ones. Similarly, the extremely online might ensure that some unmasked “Karen” gets her comeuppance for coughing in order to signal that they “believe science” or because they feel guilty about the essential workers stuck delivering pad thai to their remote office.

A less cynical view would be that online dogpiling allows people to feel like they can influence chronic social problems, issues that we struggle to resolve through official policy. Needless to say, the motivations for online shaming are various and complex. But The Crowdsourced Panopticon could have been a better guide for helping us to understand them.

Weissman’s analysis remains a technocratic one, as is most evident in his recommendations. When exploring how we ought to stop the spread of radical transparency, he limits himself to suggesting small technical and procedural changes rather than sketching the contours of a better world. Societies could make online surveillers more accountable for their behavior, disrupt network access or prohibit cameras in certain zones. Citizens could be given digital rights over their own information and the ability to petition for content removal, and we might limit the use of social media data by employers and governments.

Such changes promise to do a lot of good, but they feel insufficient compared to the magnitude of the problem. Of course, political change in democratic societies is naturally incremental, and proceeding in a piecemeal fashion helps avoid unintended harm. But that it is better to inch toward alternative worlds than to run does not mean that we shouldn’t also try to imagine them.

L. M. Sacasas has argued that tech backlashes “never amount to much,” because we seldom directly face up to the “bribe” offered by modern technology. That bribe, in the words of Lewis Mumford, is that “one must not merely ask for nothing that the system does not provide, but likewise agree to take everything offered … in the precise quantities that the system, rather than the person, requires.” Weissman argues that it would be “fruitless, and perhaps harmful” to attempt to undo social media outright. But limiting ourselves to tinkering at the edges, in the effort to foster spaces less threatening to democratic norms of free expression, feels like taking the bribe. I would have liked to see Weissman explore how the forms of artistic or expressive “abnormality” he values might be explicitly enabled or encouraged.

That exploration might have led Weissman to reconsider the role of community. Charles Taylor, writing in The Malaise of Modernity, has observed the modern “tendency to heroize the artist, to see in his or her life the essence of the human condition.” And he notes that authenticity is not something that exists in its own right, but comes from a “struggle against some externally imposed rules.” The modern framing of the human condition depicts community as mattering mainly insofar as it provides something for individuals to courageously revolt against.

On some level, Weissman recognizes the limits of unencumbered expressive individualism, arguing for the necessity of moving from “publics” toward “communities.” Publics are primarily built through speech, such as when people talk about the opinion of the “black community” on police brutality. Real community, on the other hand, is something more sociologically substantive. Weissman writes fondly of the New York City CBGB club that provided a safe space for punk music to flourish.

But Weissman follows Kierkegaard in defining community as built upon individuals who come together because they already share a passionate commitment to a common cause. Not only does this limit community to an instrument for facilitating individualism, it also risks misunderstanding members of extremely online publics, who probably believe themselves to be doing more than just chasing “likes.” At least some probably see calling out racism and misogyny, or pandemic safety sins, as a passionate commitment. The problem is that in maintaining that commitment, other people become dispensable — people whose livelihoods and reputations are deemed worth sacrificing in the effort to cleanse the public of unsavory opinions and actions.

Kierkegaard put the cart before the horse when he argued that individuals were incapable of uniting with others until they established their ethical stances for themselves. Philosophical communitarians like Michael Sandel, in contrast, have argued that at least some commitments are not (or perhaps should not be) chosen by otherwise unencumbered individuals, but are rather discovered in light of our already existing relationships and entanglements with others. It is not so important that we make passionate commitments to ideals but that we choose to relate to other people in ways that promote our individual and collective flourishing.

This is why social media fails us. As Jon Askonas and Ari Schulman have pointed out, online speech platforms cannot be effective communities. They were constructed under the misguided dream of liberal democracies that they could function as a universal marketplace for speech. But it’s a marketplace that “lauds the basest instincts” in how we engage with one another. Well-functioning online communities are built upon relationships that legitimate and shape the range of permissible speech, that have barriers to entry, and that provide incentives for productive speech. And there are meaningful alternatives to any given online community. To this analysis I would add that ideal communities also offer some pathway toward successful reconciliation and reintegration.

Askonas and Schulman advocate for moving back toward the tribalized forums that dominated the Internet before social media, and for giving up on the idea that any online space can serve as a universal public sphere. And there are still other alternatives worth exploring. Clubhouse emerged in the last couple years as a potential antithesis to Twitter. It is an audio-based chatroom, providing a seemingly safer space for spontaneity and a relief from social media’s dominant culture of denunciation. The Nextdoor app facilitates acts of sharing, commerce, and altruism in neighborhoods, and moments of vitriolic conflict seem to remain brief and geographically limited.

But I wonder if we shouldn’t direct more attention toward the character of our offline lives. And perhaps “bribe” isn’t the right word for our relationship with many modern technologies, because that relationship seems equally defined by a kind of resignation to previous ways of life being slowly snuffed out by the seemingly inexorable march of “progress.”

Social networks are not attractive simply because of the services they offer, but because they are increasingly the only game in town. Perhaps we look to them in order to fill the void left by shrinking networks of friends, ever-more spiritless neighborhoods, plummeting levels of social and political trust, and declining associational life. Peer-to-peer surveillance thrives because online dogpiling, call outs, and screaming into the virtual void satisfy an unmet need.

Online pathologies would not be so powerful if our offline lives nurtured us such that we forget to record a public freakout for the crowd’s pleasure or ire, such that we don’t care that someone is wrong on the Internet. Breaking up the crowdsourced panopticon may be less a matter of governing technological change than of fostering societies where not so many people want to play online prison guard.

Exhausted by science and tech debates that go nowhere?