I began this series of articles by describing a destination wedding that made me think of Thomas Jefferson. As I was writing this afterword, I went to another wedding in a faraway place, which put me in mind of another president, Calvin Coolidge.

The groom was a career military man from a conservative Catholic family. The bride’s family was liberal and Jewish. As I talked with the families, it became clear that they had strongly diverging ideas about issues like crime, immigration, religion, economics, and the environment. It is commonplace to observe that in the United States, and every other Western nation, these divisions have become so heated that threats of civil war and government collapse have become familiar news headlines. But at the reception there was a shared sense of happiness as the bridesmaids, beautiful young women in flowing dresses, and the groomsmen, handsome young men in dress uniforms, danced together under a splendid full moon.

The political fights that beset the nation are real and important. But at the same time people would have to be pretty far gone not to join in celebrating two nice young people beginning their lives together.

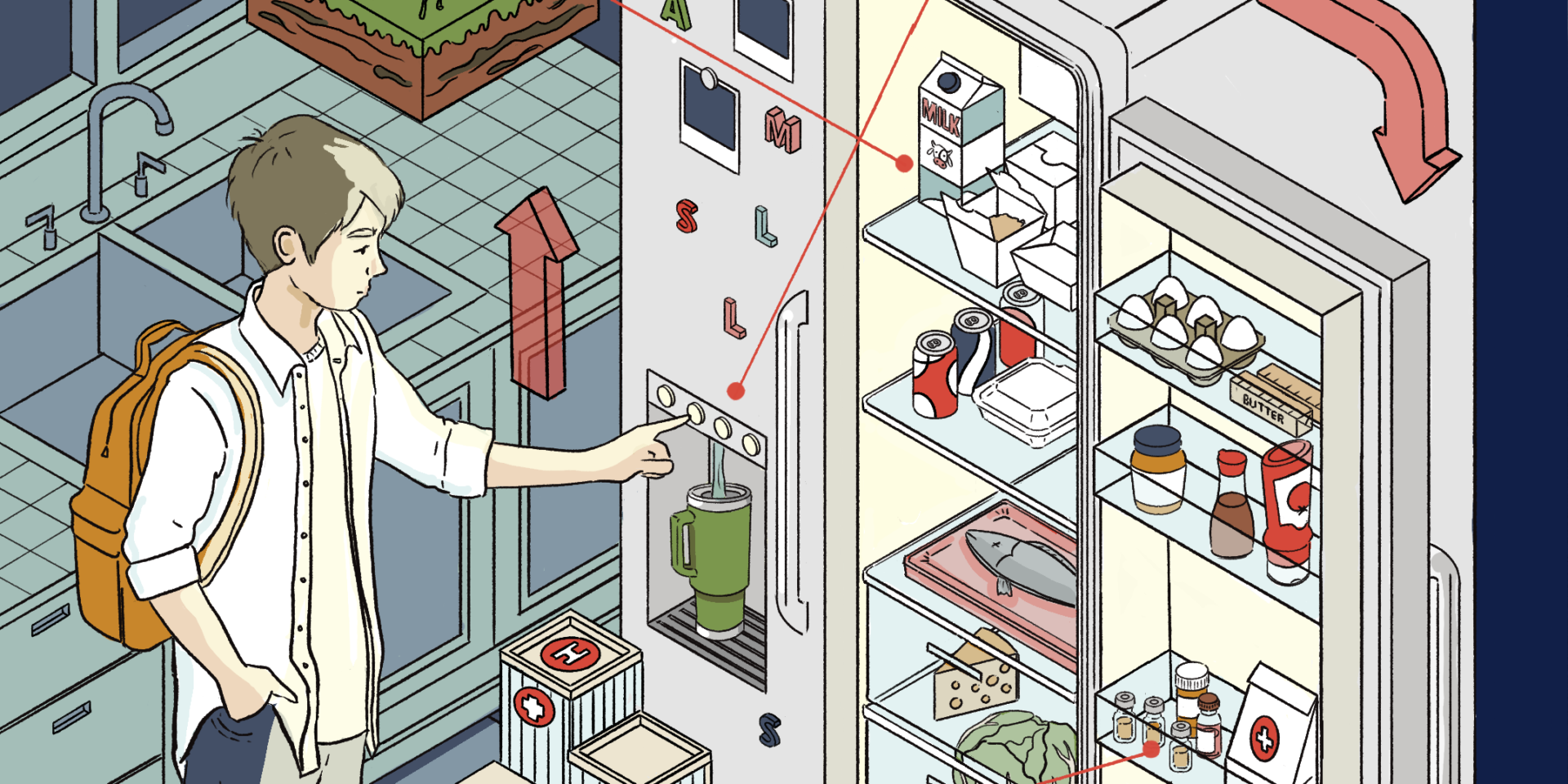

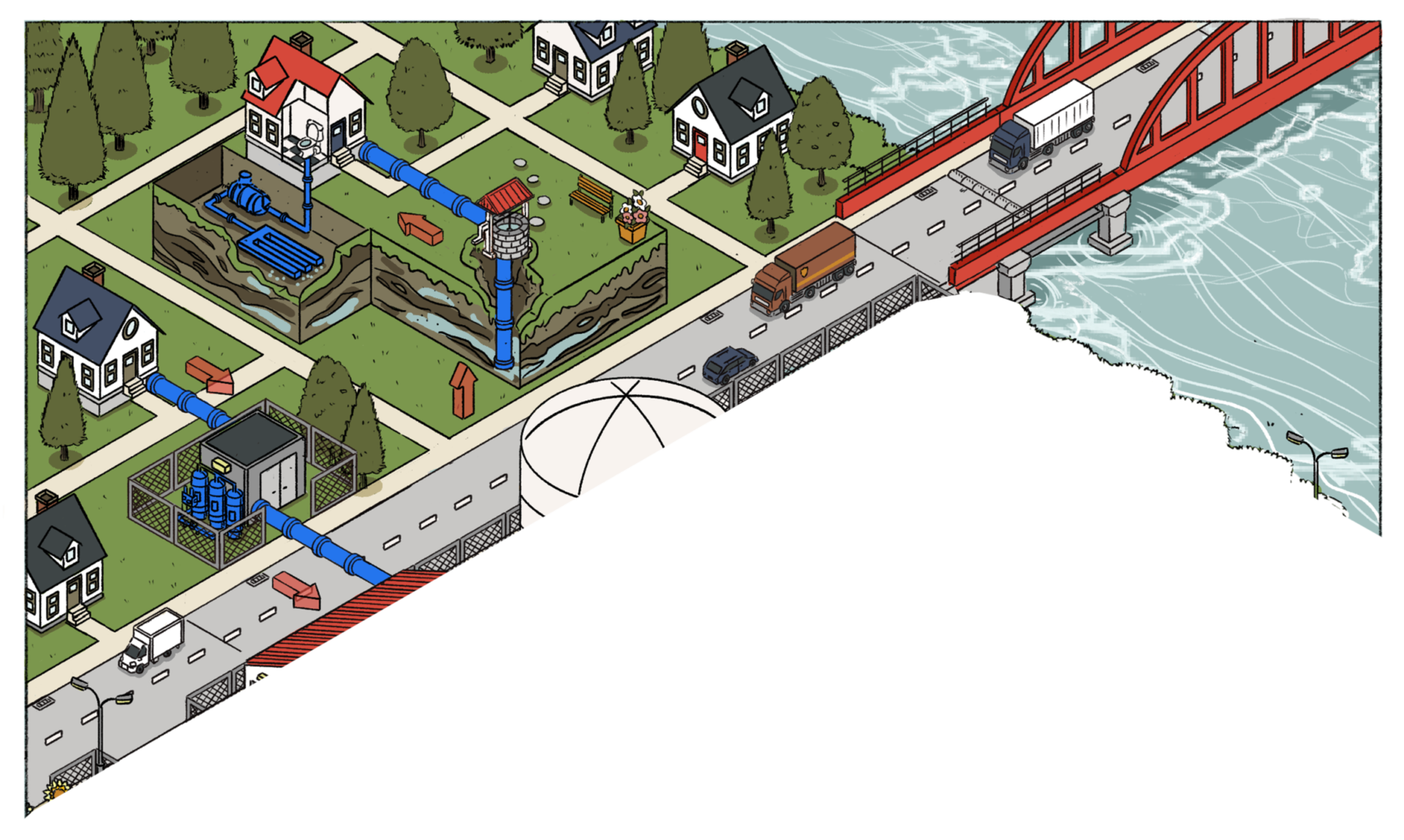

But the people at the wedding had deeper commonalities, too. All of them — like all the inhabitants of the United States and every other Western nation — stand together atop a mountain of successful efforts to improve human well-being. Conservative and liberal, atheist and believer, every race, age, and social class — each and every one has benefited from the great systems built up in the last century and a half that deliver to us good food, clean water, instant electric power, and advances in health. In every material sense, the people at the wedding were far better off than their forebears.

I was bluntly reminded of our good fortune the day after the wedding, when I visited friends who lived nearby. When I took a shower, I looked down and noticed that one of my calves was flushed and swollen. One of my legs is bigger than the other, I thought. That can’t be good.

A few hours later, I went to the emergency room, where a doctor diagnosed the swelling and redness as a skin infection: cellulitis. I asked if cellulitis is risky. “Oh, yes,” the doctor said. “These things have an excellent chance of killing you.” He prescribed antibiotics, which I bought afterward. Within a few hours of taking the first pill, the swelling had subsided. The episode was over — which put me in mind of Calvin Coolidge.

In the summer of 1924, Coolidge’s sixteen-year-old son, Calvin, Jr., played tennis on the White House grounds. For some reason, he wore sneakers without socks. He got a blister on his toe, as one might expect. It quickly became infected. The White House physician took Calvin, Jr., to Walter Reed General Hospital, then as now one of the nation’s finest health care facilities. Unsurprisingly, the son of the president got the best care available. Multiple specialists visited and the full resources of the hospital were devoted to his care. But none of this did any good. Within a week, the president’s son was dead. Coolidge went into a deep depression from which he never fully recovered.

Staphylococcus aureus, a common bacterium, was the cause of death. Staph was responsible for my infection, too. It was striking to realize that a) a century ago I might well have died; and b) the cost of maybe saving my life was three hours in the ER and $4.16 worth of antibiotics.

Another way of saying this is that I, like billions of others, have benefited from the progress humankind has made during the last century.

Progress today is a loaded word. The idea and its name both arose during the Enlightenment, when modern ideas about science first became widespread. Progress’s most important exponent was probably the French philosopher and mathematician Marie-Jean-Antoine-Nicolas de Caritat, Marquis de Condorcet, who wrote Outline of a Historical View of the Progress of the Human Mind in 1794. The Outline is a triumph of hope over experience. Its author initially supported the French Revolution, believing it would lead to more freedom, including freedom to criticize the government. But the revolutionary junta branded Condorcet as a traitor after he criticized it. He wrote about progress while hiding from the police. Soon after finishing the book, Condorcet was caught and thrown in prison. He died in his cell — possibly murdered, certainly still dreaming of progress — two days later. The Outline appeared posthumously.

Condorcet saw the increase of scientific knowledge as leading unavoidably to greater political freedom and well-being. So did most of the framers of the Constitution. But the awful wars of the twentieth century called this idea into question. In a celebrated passage written in 1940, the German writer Walter Benjamin imagined the “angel of history” turning backward to look at the past. “Where we perceive a chain of events [leading to the present], he sees one single catastrophe which keeps piling wreckage upon wreckage.” The angel would like to stop to fix the disaster, Benjamin wrote. But he can’t, because he is caught in a violent storm that hurls him helplessly forward “into the future to which his back is turned, while the pile of debris before him grows skyward. This storm is what we call progress.”

From this perspective, the idea of progress is worse than meaningless. It is a story that we tell ourselves rather than look directly at what is happening. On top of that, some critics say, these tales are used as tools to justify an unfair status quo. If Europe and North America are materially better off, that is not progress, but the profits from slavery, colonialism, and genocide. “We can find nothing in reality that might help to redeem the promise inherent in the word ‘progress,’” wrote the philosopher and critic Theodor Adorno in History and Freedom.

Adorno escaped the Nazis, who killed many of his friends and associates. Benjamin, one of his closest collaborators, committed suicide after the failure of his attempt to flee Europe. And after the war Adorno was dismayed by what he saw as German intellectuals’ clinging to German culture — its great music, writing, architecture, and so on — to avoid responsibility for the Holocaust. Adorno died in 1969, when Western cities were torn by riots, China was wracked by the Cultural Revolution, the two sides in the Cold War were racing to build ever more nuclear weapons, and warnings of imminent global famine were hitting the best-seller charts. Little wonder he doubted the idea of progress!

But Adorno lived before the Green Revolution drastically reduced world hunger. He never saw how modern anti-pollution techniques cleaned up rivers and water supplies all over Europe and North America. He never traveled to Africa, Asia, Latin America, and so did not see what it meant to have the gift of electric power. He didn’t see global public health campaigns eliminate smallpox, almost eliminate polio, drastically reduce malaria, and beat back a host of other infectious diseases.

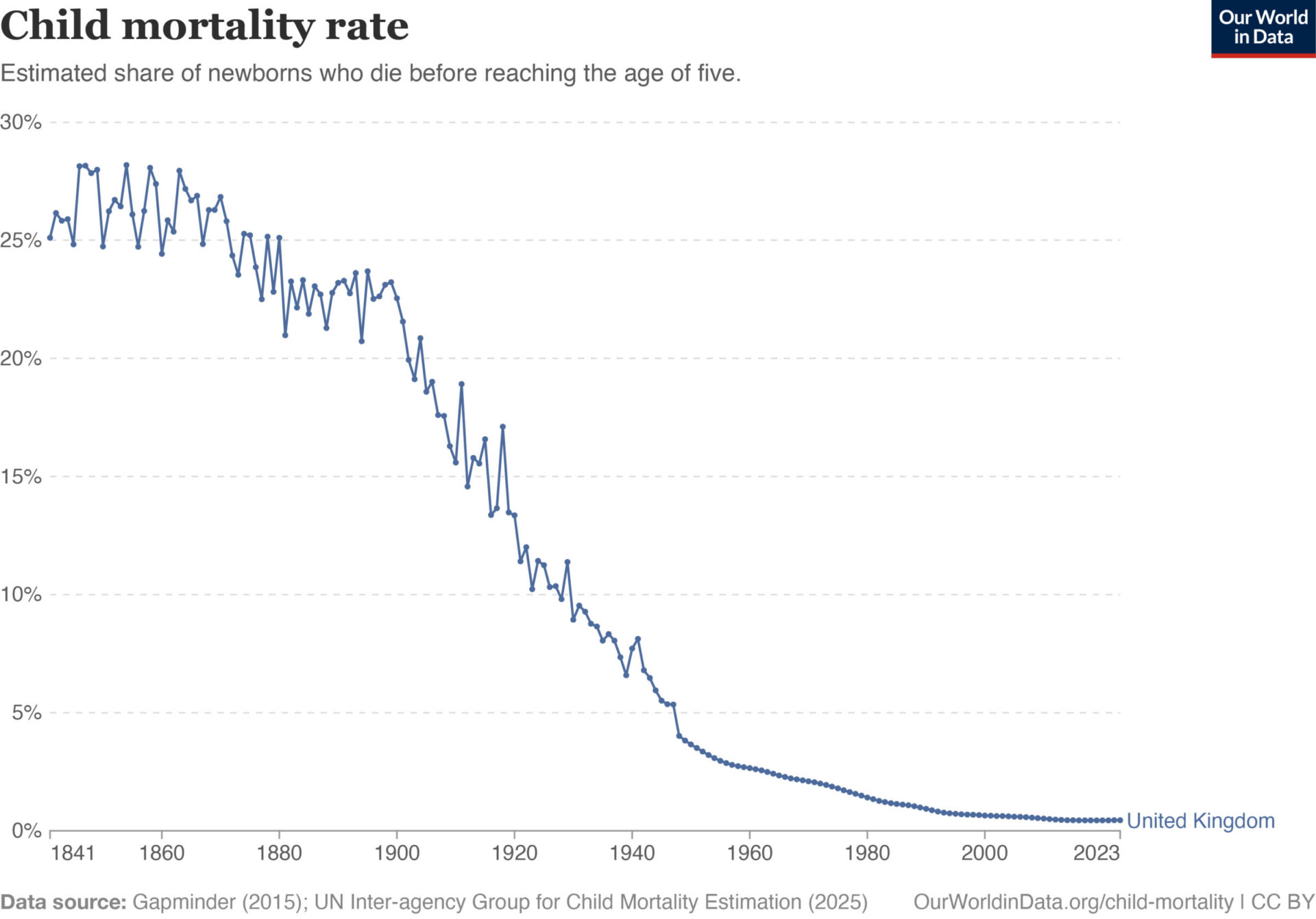

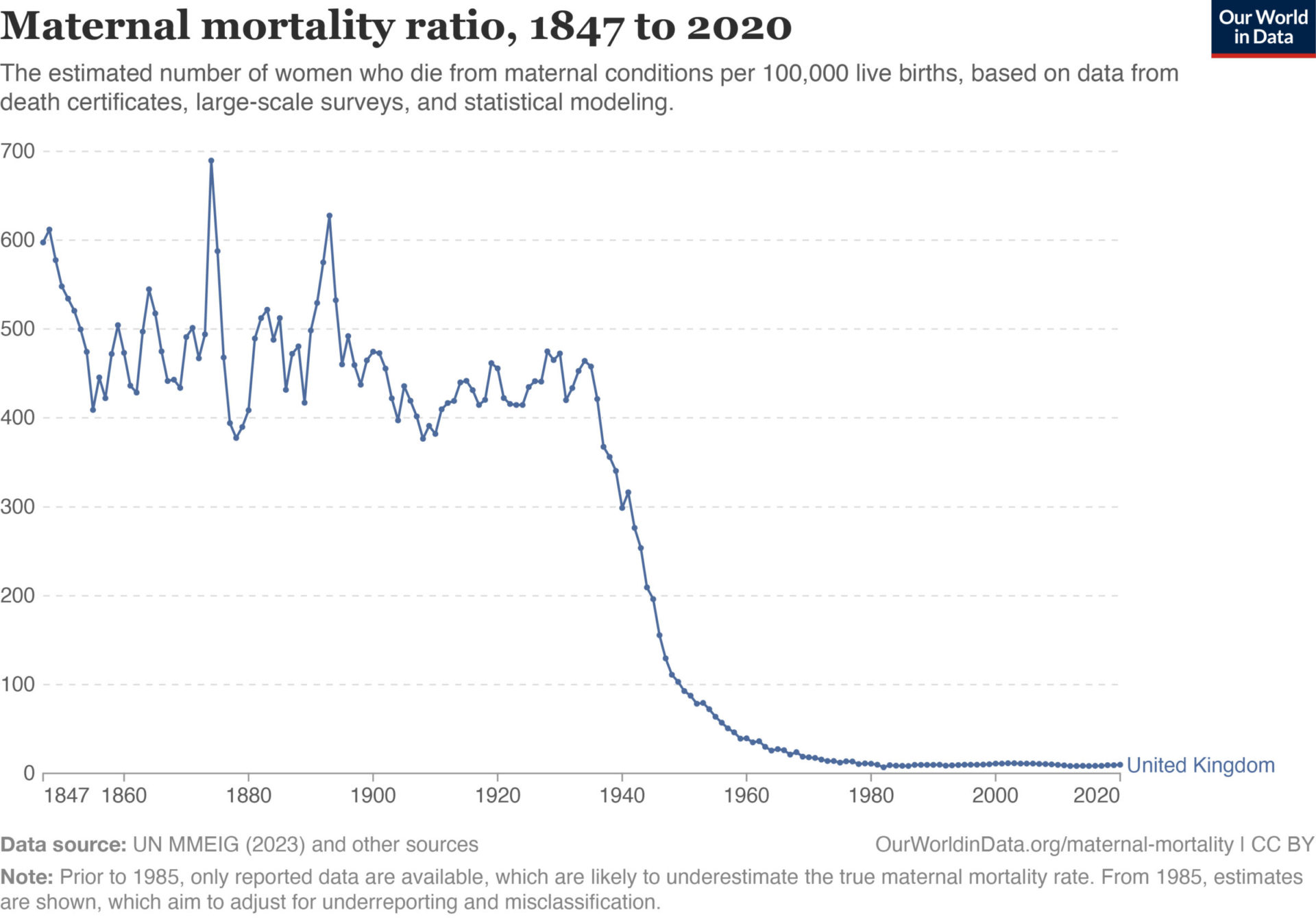

Unlike me, Adorno never had the experience of going to an emergency room that was always open to the public, or of taking a life-saving antibiotic. Instead, his experience with medicine was that of multiple doctors being unable to diagnose or treat the incapacitating ailments — migraines, nausea, fever — that afflicted his wife for decades. On a larger scale, he did not have access to contemporary data and data-visualization techniques and so never saw charts like these:

The charts show the fall in the number of British women who die during pregnancy or childbirth and the number of British children who die before the age of five. I chose Britain because it has unusually good records, but similar (if sometimes smaller) long-term declines have occurred all over the world. One would have to be extraordinarily cynical not to conclude from these charts that in fundamental ways life has gotten better.

Everywhere these and other improvements have occurred for the same reasons: better nutrition, cleaner water, more energy for heating and cooking, advances in public health. Condorcet, in other words, was partially right: the advance of science did lead to progress. But the progress was not so much political as material. And it wasn’t so much from science itself as the use of scientific advances — the invention of powerful pumps, the introduction of high-yielding crops, the discovery of electrons, the development of vaccines and antibiotics — to create systems that increased human well-being.

At the same time, Benjamin and Adorno were also partially correct. Condorcet believed that progress was inevitable, even guaranteed by natural forces. Benjamin and Adorno remind us that human failings can always make things worse. For understandable reasons, the two men thought in terms of human depravity. And it is true that terrorism, insurrection, and war, especially nuclear war, could negate much or most of the improvement in human well-being our forebears achieved.

But Benjamin and Adorno missed another, possibly more pernicious threat. Each increment of progress generates its own overhead. Even as brilliant minds pursue space flight, cancer cures, and flying cars, we also must undertake the largely invisible, sometimes thankless labor of maintaining and improving the sewage treatment plants our forebears bequeathed to us. The advances of our past are yokes around the neck of the present. The more advances, the heavier the weight of the yokes.

Power plants must be upgraded and replaced, along with power lines and distribution centers. Crops must be continually bred to face new pests and blights. Water systems must be renovated after use and wear. Medical treatments must adjust to diseases that are constantly evolving. Buildings must be renewed for new uses with new materials. And the standards behind all these efforts must be reviewed to take into account changes in science and society.

The list is long, daunting — and necessary. It is true that some new advances obviate past methods. A clear example: replacing lead pipes with plastic pipes can mean the water no longer has to be checked constantly for lead. But the systems overall will always need care. They will always be one generation from falling apart.

Sometimes it seems that in all the immediate tumult of a politically divided society the need to continue these efforts for the common good can be forgotten. These articles have been written in the hope that they will play a small part in reminding us of the need to pay attention to them. Our ancestors gave us the food, water, energy, and public health systems that undergird our world; keeping them going is how we can pass on those gifts to our children.