Amid the carnage of the Second World War, which saw some 60 million killed, including the Nazis’ industrialized annihilation of six million Jews, one event stands out in American memory as the most momentous: the atomic bomb attack that leveled Hiroshima on August 6, 1945. According to the most authoritative Japanese casualty count, which is higher than the American figure, the bomb killed some 100,000 people outright and another 40,000 over the next several months; blast, flash burns, and firestorm took care of the former, and radiation sickness accounted for the latter. A second bomb that dropped just three days later on Nagasaki killed 70,000 all told but gave some people misgivings even more troubling than those produced by Hiroshima.

Political men at the time understood, or at least appreciated sufficiently to exult in, the historic scale of the devastation. Upon getting word of the successful mission, while he was returning to the United States from the Potsdam Conference in Germany, President Harry Truman, ultimately responsible for the bombing, let off an exclamation of fiery triumph: “This is the greatest thing in history!” Secretary of War Henry Stimson nosed out the significance of the bomb well before it was put to use, and offered a more sober assessment. On May 31, 1945, in the decisive meeting to determine whether the bomb, which had not yet even been tested, should be dropped on Japan, he hailed the device not “as a new weapon merely but as a revolutionary change in the relations of man to the universe.” Its impact “went far beyond the needsof the present war” and would be apparent to all humanity in due course. Whether the bomb would elude prudent control and recoil on its creators, or whether it would serve to secure world peace, remained to be seen.

In either case, Hiroshima would become a lasting testament to the human race’s ingenuity as well as its monstrosity. James Agee, magniloquent journalist and novelist, declared in Time magazine in August 1945 that, compared to the bombing, “the war itself shrank to minor significance.” More recent commentators have shared this sense of a world-historical event unique in its consequences. In Hiroshima in America: Fifty Years of Denial (1995), Robert Jay Lifton and Greg Mitchell lead off with the assertion, “You cannot understand the twentieth century without Hiroshima.” In The Age of Hiroshima (2020), editors Michael D. Gordin and G. John Ikenberry state, “Hiroshima is a name that everyone has heard of…. The city stands as a metonym for the destructiveness of nuclear weapons.”

Ordinary Americans have chimed in on the matter in their own way. A Gallup poll taken two weeks after the bombing showed 85 percent of the public approved of it, but 27 percent also feared that atomic weaponry would one day cause universal destruction. Asked again fifty years later, only 59 percent of Americans approved of the bombings. And, asked further in 1995 whether they would have ordered the bombings if the decision had been theirs to make, only 43 percent said yes, while 50 percent would have “tried some other way to force the Japanese to surrender.”

Moral compunction about Hiroshima has evidently increased over the years, but already in 1945 regret and remorse bit some people hard and fast, while gnawing more slowly at others. Truman was concerned about disapproval from Pope Pius XII, who had warned against the development of the bomb; a Vatican newspaper accused Truman and his men of lacking Christian charity. The editors of the Catholic magazine Commonweal averred that Hiroshima and Nagasaki were the new “names for American guilt and shame.” A host of Protestant churchmen, including the virtually sainted Reinhold Niebuhr, joined in the opprobrium.

Religious personnel were not the only ones shocked and appalled. A month after the attack, Australian war correspondent Wilfred Burchett eluded General Douglas MacArthur’s prohibition against journalists’ access to the area and traveled over 400 miles from Tokyo to Hiroshima, where he found what he later described as a “death-stricken alien planet.” Sitting amidst the rubble, he issued the first public report, published in the Daily Express, of what he called an “atomic plague” that was “mysteriously and horribly” killing people who had been uninjured by the blast and flash of heat. In hospitals, Burchett found

people who, when the bomb fell, suffered absolutely no injuries, but now are dying from the uncanny after-effects. For no apparent reason, their health began to fail. They lost appetite. Their hair fell out. Bluish spots appeared on their bodies. And the bleeding began from the ears, nose and mouth.

Burchett delivered “a warning to the world” about this previously unsuspected pathology.

Perpetrators of the bombing responded with scorn. General Leslie Groves, head of the Manhattan Project, the stunning scientific and technological enterprise that had produced the bomb, shouted back that this loose talk of unexampled disease was “hoax or propaganda.” But in time all concerned had to admit the full extent of the suffering and death the bomb had caused.

What could possibly justify such terrible havoc? And how did the men who unleashed it justify it then?

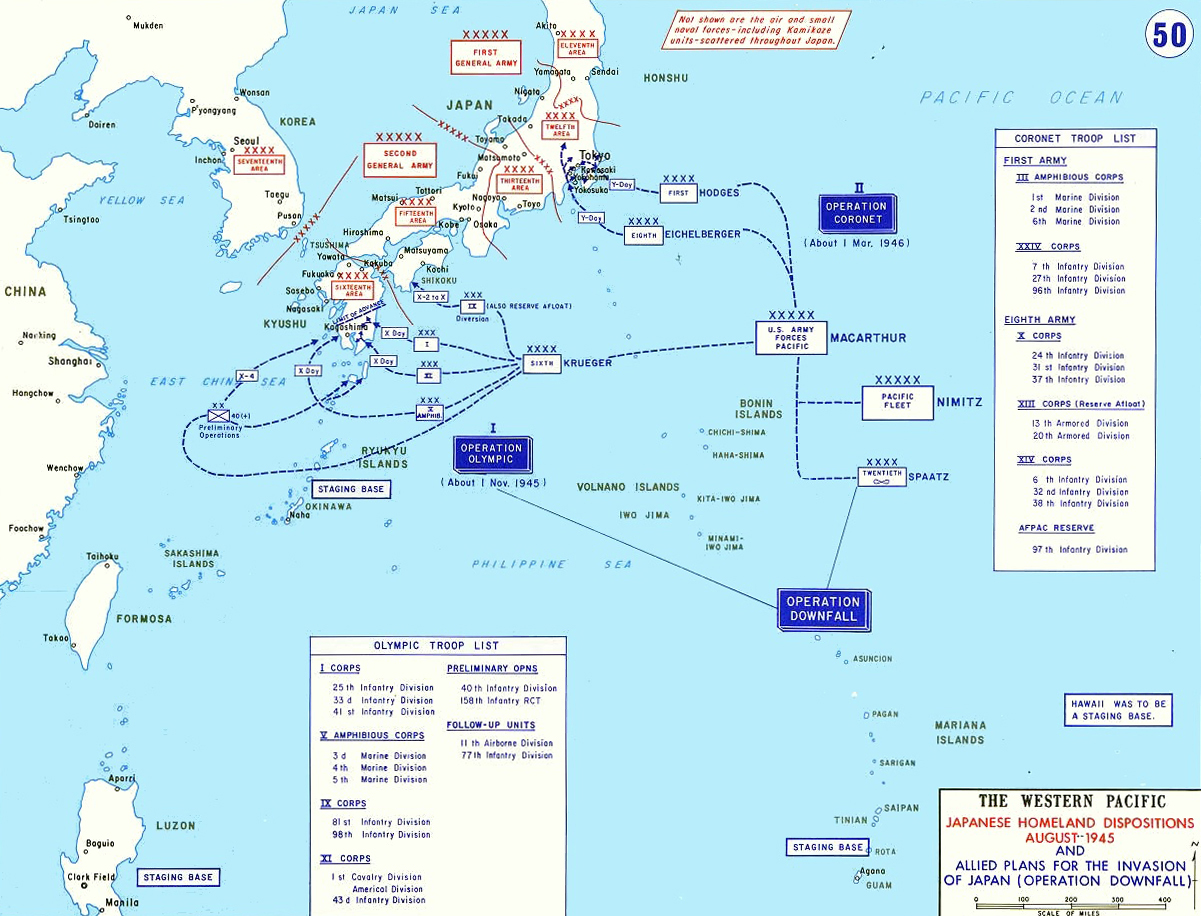

For defenders of the bombing, what justified it was their conviction that it averted an even more murderous endgame to the war: The mass assault on the Japanese homeland, the invasion of Kyushu designated “Olympic” and planned for November 1, and the follow-up operation against the main island of Honshu called “Coronet,” would have cost an estimated 500,000 to 1,000,000 American dead. Such anyway were the figures that the statistical wizard and former President Herbert Hoover had furnished for Truman at his request, and Truman would cite these and similarly chilling figures in explaining the practical value and the moral dividend of the atomic bombing. Winston Churchill for his part opined after Nagasaki that the twin bombings had spared at least 1,200,000 Allied lives, of which a million were American. General Groves found Churchill’s estimate somewhat inflated, and reckoned the total fatalities at just under one million.

These projected casualty numbers would become a contentious subject among later historians. The calculations have come to represent what their detractors call the official, traditional, conventional, orthodox, legendary, or mythic narrative, depending on the extent of their contempt for the atomic decision-makers. In place of these figures, the revisionists point to the ones cited by the military brass who actually planned the invasion and who predicted only up to 46,000 Americans dead, or half as many if the operation in Kyushu alone were to end the war. The tag “revisionists” displeases most historians of this school, who justly note that their position relies on the respected opinion of military and political experts prior to the bombings.

Resistance to the revisionist interpretation is fierce, as is disdain for the smaller figures they use. In a 1994 Washington Post article, Robert P. Newman, later author of Truman and the Hiroshima Cult, contends that leading soldiers and politicians alike were spooked by the prolific slaughter on Iwo Jima and Okinawa in the spring of 1945, and had become “so casualty-shy that they could not be candid about the ferocious Japanese resistance expected on the home islands…. [General] MacArthur especially was motivated to play down anticipated casualties.” MacArthur, the supreme Pacific commander and supreme egotist of the United States Army, wanted the opportunity to head the greatest amphibious operation ever. If the expected price in human life were too exorbitant, Truman might well prefer the slow starvation of blockaded Japan to a hell-bent mass assault.

Although one could not, as the revisionists do, expect the whole truth from those who would lead an invasion, the medical services were of necessity more trustworthy in their estimate of the potential blood-letting: “Total casualties, D-Day plus 120 — 394,859.” This would include wounded as well as dead, and, assuming quite dubiously that the invasion were to take no more than four months to succeed, those killed in action would run to over 100,000 — as many Americans as had died in the entire Pacific war to date.

Still, there is a difference of an order of magnitude between the medical corps figures and Truman’s at his most extravagant. But what reasonable commander-in-chief would willingly sacrifice even a hundred thousand of his soldiers, or, for that matter, 20,000, if there were an alternative that cost even less of his own men’s blood? Cruel as it may sound, in war one’s own soldiers are more precious than the enemy’s. Even in the most Christian of countries, universal compassion has never applied to the battlefield, and in the Second World War the battle, specifically the air war, extended to the mass destruction of non-combatants.

Calculation, the cold-blooded calibration of means to ends that political philosophers since Machiavelli have called prudence, finds itself frequently at odds with the principal moral virtue of democratic times as enunciated by Rousseau and Tocqueville: namely, compassion. “The Atomic Bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki,” a 1946 Manhattan Project report, speaks of wholesale devastation in a manner so plain and straightforward as to seem utterly callous:

Damage to buildings with structural steel frames was more severe where the buildings received the effect of the blast on their sides than where the blast hit the ends of buildings, because the buildings had more stiffness … in a longitudinal direction. Many of the lightly constructed steel frame buildings collapsed completely while some of the heavily constructed … were stripped of roof and siding, but the frames were only partially injured.

If one does not instinctively wonder about the fate of the people trapped inside these buildings, one likely possesses the protective emotional carapace essential to existence in the atomic age.

The Manhattan engineers speak of incinerated human beings with the same scientific and militarized detachment as they do of collapsed buildings:

To summarize, radiation comes in two bursts — an extremely intense one lasting only about 3 milliseconds and a less intense one of much longer duration lasting several seconds. The second burst contains by far the larger fraction of the total light energy, more than 90%. But the first flash is especially large in ultra-violet radiation which is biologically more effective. Moreover, because the heat in this flash comes in such a short time, there is no time for any cooling to take place, and the temperature of a person’s skin can be raised 50 degrees centigrade by the flash of visible and ultra-violet rays in the first millisecond at a distance of 4,000 yards.

“Biologically more effective” is a blood-curdling phrase, as though flash burns, clinically measured in this account, have no other effects. Human souls and the trauma they endure have no place here.

One can hardly imagine, however, that decreeing the horrific death of thousands of civilians did not exact at least a modicum of anguish from the bomb makers and the men who commanded them. Edward Teller was a principal figure in the Manhattan Project, and later spearheaded the development of the hydrogen bomb, a weapon a thousand times more powerful than the Hiroshima bomb. His admirers and detractors alike fingered him as having partly inspired Stanley Kubrick’s Dr. Strangelove. In his Memoirs: A Twentieth-Century Journey in Science and Politics, Teller quotes at length from a letter he wrote in July 1945 to Leo Szilard, another formidable atomic brain and the most impassioned and persistent scientific opponent of ever using the bomb. “First of all, let me say that I have no hope of clearing my conscience. The things we are working on are so terrible that no amount of protesting or fiddling with politics will save our souls.” Yet Teller goes on to reject Szilard’s efforts to prohibit the bomb’s use forever.

I do not feel that there is any chance to outlaw any one weapon. If we have a slim chance of survival, it lies in the possibility to get rid of wars…. Our only hope is in getting the facts of our results before the people. This might help to convince everybody that the next war would be fatal. For this purpose actual combat use might even be the best thing.

Teller’s revulsion at the suffering and death his work shall cause gives way before the hope that using the bomb may result in the abolition of war and thus transform the agent of annihilation into the ultimate life-saving device. Compassion will not be undone by calculation here, for Teller is actually calculating in the interest of the most compassionate project in history: the establishment of perpetual peace. How wholeheartedly he believed that such a wonder might be possible is unclear. Human ingenuity in rationalizing one’s actions is pretty well limitless.

J. Robert Oppenheimer, the scientific leader of the Manhattan Project, was whipsawed between the tender feelings of the compassionate soul on the one hand and, on the other, the icy ambition required to delve into the hidden secrets of the universe as well as the native ruthlessness of the patriotic happy warrior. At the successful Trinity test explosion of the bomb in the New Mexico desert in July 1945, a fellow physicist observed with considerable distaste Oppenheimer’s “High Noon … kind of strut.” And announcing Hiroshima’s obliteration to a packed and howling auditorium of colleagues, Oppenheimer pumped his clasped hands in the air like a boxer after knocking out his rival. That he then told the ever more delirious crowd his sole regret was failing to get the bomb ready in time to punish the Germans may not improve his standing as a humanitarian, but it should at any rate exonerate him of the charge that the atomic bomb was a racist instrument intended exclusively for the Japanese.

Yet such touches of inhumanity in Oppenheimer’s character are hardly the whole man. The Trinity detonation brought to his mind his beloved Bhagavad Gita, and the words of the god Vishnu: “Now I am become death, the destroyer of worlds.” There is no more poignant testimony to the guilty ache in Oppenheimer’s soul than this quotation, which he and others repeated for public consumption until it became his signature line. Even this utterance reveals a telling ambiguity. For Vishnu says these words while exhorting Prince Arjuna to embrace his duty as a warrior to kill — nothing less than his destiny, really, well beyond the bounds of conventional good and evil.

Oppenheimer’s biographers, and two of the foremost revisionist historians, Kai Bird and Martin J. Sherwin, in American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer (2005), reduce the lesson their subject learned from the revered text to the need for unwavering focus on the assignment before him: “celebrate work, duty and discipline — and worry little as to the consequences. Oppenheimer was acutely attuned to the consequences of his actions, but, like Arjuna, he was also driven to do his duty. So duty (and ambition) overrode his doubts — though doubt remained, in the form of an ever-present awareness of human fallibility.” Bird and Sherwin believe the atomic bomb was not a military necessity and should never have been used, and they pin as much guilt on Oppenheimer as they possibly can. When in preparation for the bombing Oppenheimer, in gloomy distraction, was once heard saying of the Japanese, “Those poor little people, those poor little people,” the biographers snidely mock his evident sorrow as hypocrisy or, at best, self-delusion: “That very week, however, Oppenheimer was working hard to make sure that the bomb exploded efficiently over those ‘poor little people.’”

While working to ready the bomb for action, Oppenheimer may have permitted himself the free flow of compassion for its victims — his victims — only rarely. But when the war was over, he expressed his feelings unguardedly, as he did in remembering the decency that Secretary of War Henry Stimson expressed at the critical meeting on May 31, 1945 to decide whether to drop the bomb on Japan. In Oppenheimer’s telling, Stimson lamented the depth of “degradation” to which all combatant nations had sunk. None was innocent of

the appalling lack of conscience and compassion that the war had brought about … the complacency, the indifference, and the silence with which we greeted the mass bombings in Europe and, above all, Japan. He was not exultant about the bombings of Hamburg, of Dresden, of Tokyo.

Richard Rhodes, in The Making of the Atomic Bomb (1986), the fullest account I know of the scientific, political, and moral events that transformed the world, quotes this postwar recollection of Oppenheimer’s as a cry from the heart in solidarity with Stimson, while revisionists Bird and Sherwin in their biography never mention this admiring observation, but instead emphasize that Oppenheimer at the fateful meeting failed to restrain the gung-ho bombers: he “had won nothing and acquiesced to everything.” In Rhodes’s account, Oppenheimer, with all his flaws and tangles, emerges as the man most profoundly responsive to the moral and emotional tumult in which the atomic age began.

Having resigned as director of the Manhattan Project after the war, Oppenheimer gave a speech before the new Association of Los Alamos Scientists (ALAS, pointedly), professing his complicated faith in the integrity of disinterested scientific exploration of the whole of Creation, the imperfect justice of the bomb for which many felt misgivings or even guilt, and the dread of untold destruction the future held. The unprecedented peril, he urged, required “a new spirit in international affairs” — the realization that beneath the things Americans cherished most deeply and were willing to die for, including democracy, “there is something more profound…; namely, the common bond with other men everywhere.”

That common bond is the basis of democratic compassion, an almost natural reflex in modern societies but unthinkable in aristocratic times. It is what Tocqueville described in Democracy in America:

When ranks are almost equal in a people, all men having nearly the same manner of thinking and feeling, each of them can judge the sensations of all the others in a moment…. It makes no difference whether it is a question of strangers or of enemies: imagination immediately puts him in their place. It mixes something personal with his pity and makes him suffer himself while the body of someone like him is torn apart.

This trembling at others’ pain, which we see at times in Oppenheimer, is at the core of modern historiography, where it is most conspicuous in accounts of wartime suffering and death. But compassion also often dovetails with oppressive feelings of personal inconsequence. In the chapter “On Some Tendencies Particular to Historians in Democratic Centuries,” Tocqueville writes of the tendency to make individuals seem helpless in the grip of vast historical forces, what he calls a “doctrine of fatality” that threatens to ravage the belief in free will. Suffering with those one sees suffering exacerbates the vulnerability that all persons feel while war rages — especially the total war in which civilian lives are made precarious daily. Compassion, solidarity in agony, rebounds upon the individual soul, which feels all the more acutely the meagerness of its own powers.

Against these democratic tendencies, Tocqueville sets the confidence of historians who see the fate of nations and indeed of entire epochs as dependent on the actions of a relative handful of dominant characters. “When historians of aristocratic centuries cast their eyes on the theater of the world, they perceive first of all a very few principal actors who guide the whole play.” Tocqueville’s contemporary Thomas Carlyle, something of a throwback in his taste for world-altering aristocratic genius, elaborates on this theme in On Heroes, Hero-Worship, and the Heroic in History:

For, as I take it, Universal History, the history of what man has accomplished in this world, is at bottom the History of the Great Men who have worked here. They were the leaders of men, these great ones; the modellers, patterns, and in a wide sense creators, of whatsoever the general mass of men contrived to do or to attain; all things that we see standing accomplished in the world are properly the outer material result, the practical realization and embodiment, of Thoughts that dwelt in the Great Men sent into the world: the soul of the whole world’s history, it may justly be considered, were the history of these.

To be a Great Man in political thought and action, being pulled by the magnetism of an abstract political idea that may or may not be true, often demands the renunciation of compassion, the rejection of such truth as one’s fundamental humanity intimates. Among scientists, the exemplar of this division of soul from mind is Oppenheimer; among politicians, it is Truman.

The Missouri farmboy Harry Truman was a bookworm with a masterly recall of whatever he read, and there were two books that he would read and reread with a hungry mind: Plutarch’s Lives of the Noble Greeks and Romans and Charles Horne’s four-volume Great Men and Famous Women. These biographies of heroes worked on Truman like a magic spell: under their influence, his avid nature craved to do great deeds and, perhaps to a lesser extent, to think great thoughts.

Of the presidents that Americans especially admire, Truman was likely the most ordinary, and many considered this his most winning characteristic. He seemed like a regular guy who’d had greatness, or at least its possibility, thrust upon him. Whether he knew what to make of it remained unclear, but the multitudes were pulling for him. President Franklin Roosevelt picked him as running mate for his fourth term not for his intrinsic excellence but as a sop to big labor. Truman did not want the job and had to be talked into it, as the admiring David McCullough details in his 1992 biography Truman. He especially did not relish the thought of inheriting the presidency should Roosevelt’s poor health result in his death.

When Roosevelt’s passing in April 1945 elevated Truman to the White House, he felt unready for the task. “I’m not a superman, like my predecessor,” he would protest. “I’m not big enough for this job.” As the new responsibilities became clearer, he seemed ever punier to himself. The Manhattan Project was such a closely kept secret that Roosevelt had never told his vice president of its existence, so when Secretary Stimson informed him of it he nearly groaned under the weight. But when during the Potsdam Conference — the meeting in Germany of the Allied leaders — he received news of the successful Trinity test, he suddenly acquired a noticeable élan, handling Stalin with an aplomb no one would have suspected he possessed. A working weapon made the ordinary man extraordinary.

Robert Jay Lifton and Greg Mitchell do not share McCullough’s esteem for Truman’s fundamental decency, competence under duress, and guiding sense of his immense role in ordering the atomic bomb attacks. In these revisionists’ eyes, Truman battled against the best in himself and won all too easily. “A decent man, Truman felt it necessary to suppress his own compassion.” He suffered “numbing and dissociation in connection with the bomb” that prevented him from acknowledging his actions. To secure Japanese surrender and thus to save American lives was “the only acceptable motivation,” so he seized on that while doing his best to ignore the morally unacceptable motivations, which were just as real: to strike fear into the Soviets and to assure his fellow Americans that the two billion dollars (33 billion today) that the Manhattan Project cost had been well spent. For a staggering world-historical event, the money seems petty, but there it is. Lifton and Mitchell also note that Truman felt “profound anxiety about the effects on the American public of a congressional investigation of an unproductive Manhattan Project.” To build the bomb without using it, Truman feared, would be an unconscionable waste of funds, at least in the public mind. But the two historians prefer not to probe a more legitimately unconscionable consequence of failing to use the bomb: How would the American public respond if a land invasion of Japan proved a bloodbath and they discovered the existence of a super-weapon that would have obviated that slaughter? The smaller the revisionists can make Truman look, the better for their cause, if not necessarily for the truth.

The revisionists’ Truman is unaware of the unprecedented nature of the weapon he loosed upon the world. As he told John Hersey, who in 1946 wrote what is still the most famous book about Hiroshima, the modern aspirant to high statesmanship cannot do better than to hone the mind exclusively on the classics: “Nothing but the lives of great men! There’s nothing new in human nature; only our names for things change. Read the lives of the Roman emperors from Claudius to Constantine if you want some inside dope on the twentieth century.” Truman’s mistake, according to Lifton and Mitchell, is to rely on history rather than philosophy for finding the moral locus of the bombings. He was a student of history smitten with the tales of great men of old, but failed to recognize that understanding the past will not help him understand his unique present — a present begotten by a novel weapon that could wipe mankind off the face of the earth, the fruit of painfully enhanced knowledge of good and evil that the instruction in Eden had never quite broached.

Yet without recognizing any contradiction — the inconsistency wholly Truman’s — Lifton and Mitchell show that Truman did appreciate fully that he possessed a device of devastating potency the world had never seen, was anguished over using it, and avowed that after Hiroshima and Nagasaki he would not employ it again. In a 1948 campaign speech, he emphasized his sorrowful singularity:

That was the most terrible decision that any man in the history of the world had to make…. I never want to have to do that again, my friends…. Right then and there I made up my mind that that must never happen again if it could conceivably be avoided.

This sounds like a sober assessment and earnest confession of barely thinkable deeds.

But the two historians undercut the solemnity of the declaration. At a well-lubricated dinner that Truman hosted for Churchill and some high American officials, Churchill merrily raised the question of how Truman and he would justify dropping the bombs upon reaching St. Peter at the gates of heaven. Instead of Truman answering, others deflected the question and put Churchill himself on trial, who demanded a jury of his peers. Some acted as figures like Alexander the Great, Socrates, and George Washington, with Truman the presiding judge. The greatest of Englishmen was found not guilty. By implication, so was Truman, who, of course, was the one who had made the decision to bomb. Lifton and Mitchell argue that such antics prove Truman never truly faced the full gravity of his responsibility: “After ordering the use of two atomic bombs, Truman spent the rest of his life in the throes of unrealized guilt.” He dimly perceived the outline of American evil, principally his own, as though in a twilight haze, but this intimation was squelched by “that American sense of our fundamental goodness being so strong that actions on our part that seemed cruel or aggrandizing should not be understood as such.”

Not Truman alone but all Americans are in the dock. The persistence of the ruinous official narrative of atomic history implicates every one of us. The revisionist historians are in business to set our souls right.

Although the revisionists did not constitute a self-conscious school until the 1960s, Kai Bird and Lawrence Lifschultz in their anthology Hiroshima’s Shadow gather a host of journalistic first responders appalled by the bombings, who might be said to anticipate revisionism. The very day after Hiroshima was hit, the French philosopher Albert Camus considers the horrifying revelation “that any city of average size can be totally razed by a bomb the size of a soccer ball.” The new depths of technological savagery, as “science devotes itself to organized murder,” demonstrate that the Allied powers have joined the race to the abyss. “We can perceive even better that peace is the only battle worth waging. It is no longer a prayer, but an order which must rise up from peoples to their governments — the order to choose finally between hell and reason.”

Six weeks later, commenting on Japan’s surrender and a potentially dangerous occupation by American forces, the theologian Reinhold Niebuhr suggests that we brought Pearl Harbor on ourselves, racist chauvinists that we are: “If we make that analysis honestly we will have to admit that our racial pride contributed to the tension which finally resulted in war with Japan.” Not only did we use more fearsome weapons against Japan than they used on us, but in our terrible victory we are beginning to succumb to “the perils of vainglory.” “The same power which encompassed the defeat of tyranny may become the foundation of a new injustice.”

Historian Lewis Mumford in 1946 hollers through a megaphone as though his were the sole sane and urgent voice trying not to be drowned out. “We in America are living among madmen. Madmen govern our affairs in the name of order and security. The chief madmen claim the titles of general, admiral, senator, scientist, administrator, Secretary of State, even President.” The only way to avoid “universal extermination” is to “treat the bomb for what it actually is: the visible insanity of a civilization that has ceased to worship life and obey the laws of life.”

America must grow a working conscience in order to have a hope of salvation. In a 1974 essay, history professor Michael J. Yavenditti examines John Hersey’s best-selling little book Hiroshima (1946), a founding document of revisionism avant la lettre. In Hersey’s time, “Americans not only approved the atomic bombings, they also became increasingly apathetic about the controversy regarding the bomb’s use.” As outraged voices cried out about the abomination of radiation sickness, General Groves placated the public with the assurance he’d had from doctors that “it is a very pleasant way to die.” It is hard to tell whether Groves was demented, delusional, or psychopathic when saying this. What kind of man can deceive himself like that, if he is in fact self-deceived and not simply lying through his teeth? Presumably, such moral confidence from on high did convince enough people so that radiation sickness never became a focus of popular dissidence. But then Americans were unlikely, with the war just over, to dwell upon horrors most convenient to forget, particularly if they might have to bear some of the guilt for them.

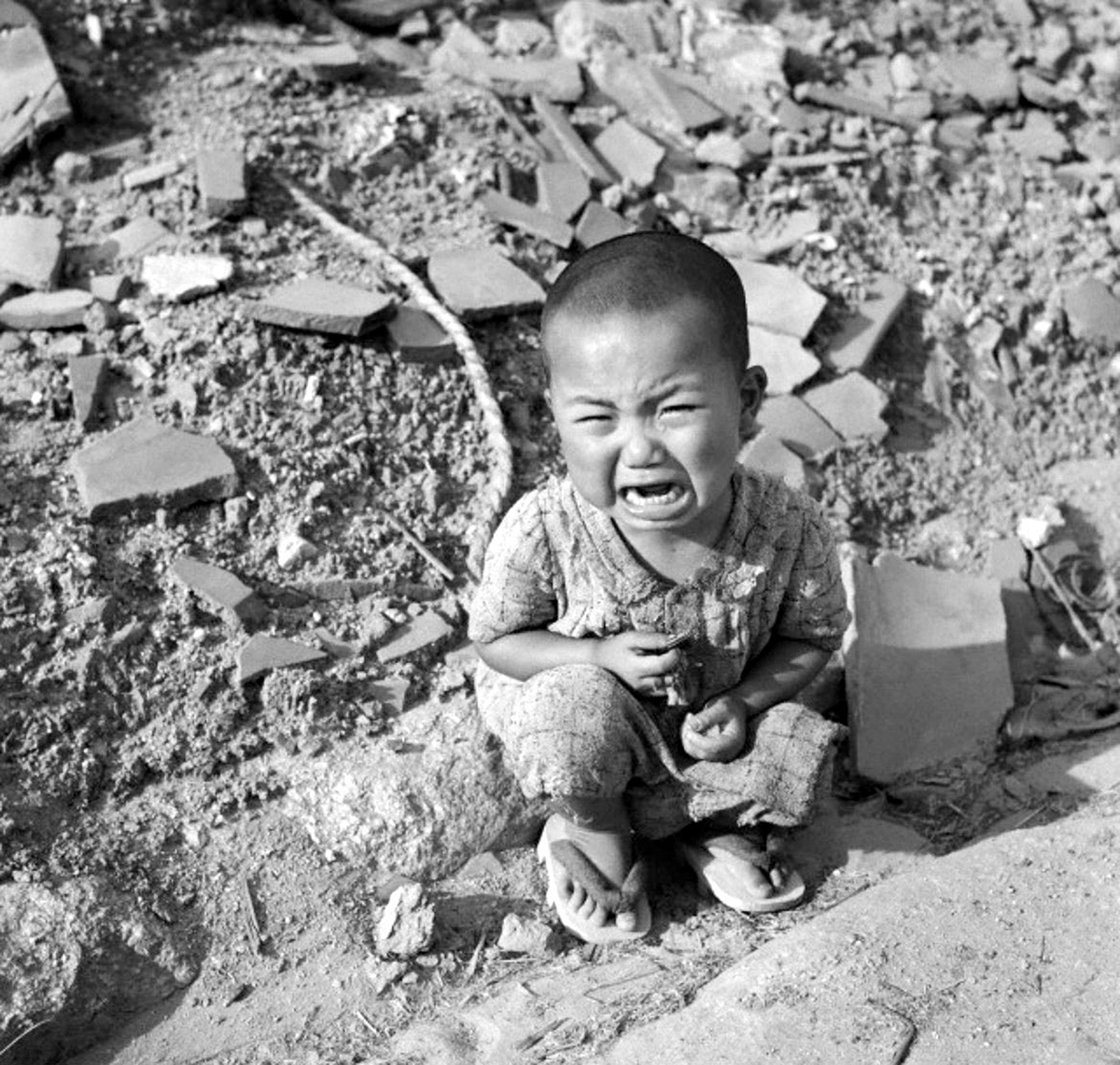

Hersey’s book epitomizes the ethos of democratic compassion. His account follows six Hiroshima residents on the fatal day, as they react to the shock and awe of the burning flash and the pillar of fire, struggle to save their own lives, help who they can, and try to preserve their sanity in the Hieronymus Bosch hellscape. Here the Reverend Mr. Kiyoshi Tanimoto, a Methodist minister with a degree from Emory University, comes to the aid of several groups of sufferers, most of them evidently dying:

He reached down and took a woman by the hands, but her skin slipped off in huge, glove-like pieces. He was so sickened by this that he had to sit down for a moment. Then he got out into the water and, though a small man, lifted several of the men and women, who were naked, into his boat. Their backs and breasts were clammy, and he remembered uneasily what the great burns he had seen during the day had been like: yellow at first, then red and swollen, with the skin sloughed off, and finally, in the evening, suppurated and smelly. With the tide risen, his bamboo pole was now too short and he had to paddle most of the way across with it. On the other side, at a higher spit, he lifted the slimy living bodies out and carried them up the slope away from the tide. He had to keep consciously repeating to himself, “These are human beings.”

Hersey’s unspoken injunction is perfectly apparent: bear it if you can, and own up to your part in it. If you have cheered the bombing that gave the Japanese a taste of American justice for Pearl Harbor, the Bataan Death March, the unspeakable mistreatment of war prisoners, the Mengele-like medical experiments, and countless other atrocities, realize that this is what justice looks like. One cannot read Hersey and exult in the victory of superior technology. The victims of Hiroshima were mostly women, children, and men too old and feeble to fight. In no moral calculus did they deserve what was done to them. Hersey never indicts American leadership for the devastation. He doesn’t need to; statements of fact about events on the ground are sufficient unto the day.

Perhaps the Japanese soldiers stationed in the city who were killed or wounded received their just punishment. In any case, here is what happened to some of them, as witnessed by a German missionary priest, Father Wilhelm Kleinsorge:

… as he looked for his way through the woods, he heard a voice ask from the underbrush, “Have you anything to drink?” He saw a uniform. Thinking there was just one soldier, he approached with the water. When he had penetrated the bushes, he saw there were about twenty men, and they were all in exactly the same nightmarish state: their faces were wholly burned, their eyesockets were hollow, the fluid from their melted eyes had run down their cheeks. (They must have had their faces upturned when the bomb went off; perhaps they were anti-aircraft personnel.) Their mouths were mere swollen, pus-covered wounds, which they could not bear to stretch enough to admit the spout of the teapot.

If the satisfactions of vengeance form some part of one’s emotional response to the bombing, perhaps one gets as much as he needs here.

Although the horror-show passages in Hersey are unforgettable, most of the account is matter-of-fact, quietly jolting: the lives of ordinary men and women upended by an event so monumental that, viewed from the historian’s customary height, they barely seem to figure in it, what happens to them significant only to themselves and their loved ones. To democratic historians driven chiefly by compassion, however, every life they detail represents thousands of others whose stories are never told. And every last one matters.

Hersey is the perfect model for a later historian such as Richard Rhodes, who devotes twenty pages of his 1986 The Making of the Atomic Bomb to a series of first-person vignettes by Hiroshima survivors relating some of the worst things they experienced, and Robert Jay Lifton, whose 1968 Death in Life: Survivors of Hiroshima contains moving interviews with hibakusha. That word literally means “bomb-affected persons,” whose horrendous scars and radiation-tainted blood, rumored or real, had made them pariahs in their homeland. Lifton makes an object lesson of the arch-liberal Eleanor Roosevelt of all people, guilty of unacceptable insensitivity toward the victims in 1953, when she mortified many hibakusha by saying that, though the bomb was a terrible thing, it might conceivably have to be used again in defense of peace. What redeems her in the sufferers’ eyes, and Lifton’s, is her outpouring of pity for the “Atomic Bomb Maidens” she met, grossly disfigured young women brought to New York by American charity for the most adept plastic surgeons to repair the damage as far as possible: “Mrs. Roosevelt’s behavior strikingly demonstrates the contrast between the direct emotional impact of visible atomic bomb effects … and the psychic numbing which can be imposed upon anyone by general ideological commitments.”

Moral truth will prevail when the compassionate soul encounters another’s suffering. This is Lifton’s belief, and, indeed, the canonical revisionist credo: If only the right people had recognized what is real, Hiroshima would have been an impossibility.

Compassion as the core of moral wisdom, calculations of prudence as insufferable casuistry: these are the ethical lineaments of the revisionists’ response to Hiroshima. Those who best understand how to think and, more important, how to feel about such an enormity do so instinctively, as Tocqueville said democratic people do. The spectacle of others’ intense suffering readily points them toward right thought and action. But then those who argue in defense of the atrocity — can one really call it anything else? — must be missing some essential piece of human equipment or have some impediment in their nature that interferes with the instinctive rush of compassion. They are beguiled by “general ideological commitments,” as Lifton writes. Their intellectual resistance must be overcome before they can see the truth — they must “see it feelingly,” as Gloucester does in King Lear in the insight of unparalleled agony, with his eyes gouged out. In short, those who justify Hiroshima must be schooled in just perception by those who know Hiroshima to be an unforgivable wrong.

But revisionist historians cannot merely bombard the opposition with horror upon horror and hope for repentance and redemption; they are compelled to resort to reason, marshal evidence, prepare a brief. Yet whatever arguments they make, the revisionists’ beliefs have their origins in primal emotions: horror, fear, disgust, rage, all directed at the perpetrators of the bombings, and not exactly reasonably at the weapons themselves. The animating force is revulsion and the conviction of their moral superiority to those who could plan and execute the abominations — and, by extension, to those who defend them.

The orthodox believers trade in the same passions but direct them at the Japanese enemy. They are patriotic in a way the revisionists are not, unashamedly preferring their own to the other, willing to discern moral clarity in American actions where ambiguity exists, or even to excuse irreparably soiled outcomes of hard decisions. They are more inclined than the revisionists to accept an implacable ferocity at the heart of life: the world’s cruelty is a given, and if they are sometimes required to contribute their fair share to it, they will. The conventional narrative of Hiroshima and the revisionist alternative represent two ways of responding to the harshest terms of existence. One sees unavoidable tragedy where the other sees the lost opportunity for amelioration, the possibility foreclosed of a more ethical end result.

In the eyes of the revisionists, orthodox historians who persist in the belief that the bombings were the “least abhorrent choice,” in the words of Secretary of War Henry Stimson, are engaging in “the denial of history,” as Kai Bird and Lawrence Lifschultz put it. The orthodox are not merely bad historians; they have abandoned the profession of history itself in order to indulge in dishonest political polemic.

For evidence of the denial, revisionists point to the appearance of revealing documents about Truman’s thinking as he prepared his crucial decision. The discoveries of his Potsdam diary in 1979 and of letters to his wife in 1983 make it impossible to cling to the conventional narrative with any intellectual integrity, Robert L. Messer argues in the 1995 essay “New Evidence on Truman’s Decision.” The diary shows indubitably that Truman understood the bomb was not the only alternative to invasion as the winning blow against Japan. Stalin joining the war against Japan would be the kill shot, he confided to his diary on July 17: “He’ll be in the Jap War on August 15th. Fini Japs when that comes about.” Truman’s letter to his wife the next day clinches his certainty, and Messer’s, that the Soviet entry was decisive in ending the Pacific war:

I’ve gotten what I came for — Stalin goes to war on August 15 with no strings on it…. I’ll say that we’ll end the war a year sooner now, and think of the kids who won’t be killed! That is the important thing.

Messer seizes upon these passages as proof that Truman dropped the bombs even though he knew they were unnecessary to compel Japanese surrender. “If he believed that the war would end with Soviet entry in mid-August, then he must have realized that if the bombs were not used before that date they might well not be used at all.” And not to use the bombs was all but unthinkable. Truman was weighing the cost averted in American soldiers’ lives when he mentioned the kids who would be saved; with Japanese children’s lives he could be more profligate. Although Truman had heard of the atomic bomb only upon taking office in April 1945, Messer writes, he intuitively “grasped this new technology, and used it as a solution for a multitude of military, political, and diplomatic problems.”

But Messer makes too much of this diary entry and letter home, presuming that here were Truman’s definitive thoughts — unquestionable precisely because they were unofficial, unguarded — about the war’s end, the timing of which was to depend entirely on the Soviets’ action. It seems rather that Truman was trying these thoughts on for size while he needn’t take presidential responsibility for them. The letter to his wife Bess was written early in the morning on July 18, David McCullough recounts, hours before Truman received a coded telegram reporting the successful test of the bomb in New Mexico. The news plainly excited him, and likely helped him make up his mind then and there. Later that day, he wrote in his diary, “Believe Japs will fold up before Russia comes in. I am sure they will when Manhattan appears over their homeland.” McCullough suspects that, although the decision to drop the bomb was ultimately the president’s, his advisors at Potsdam voiced a “consensus … that the bomb should be used,” and Truman never took a stand apart from this general agreement.

Most likely, he never seriously considered not using the bomb. Indeed, to have said no at this point and called everything off would have been so drastic a break with the whole history of the project, not to say the terrific momentum of events that summer, as to have been almost inconceivable.

General Groves rather churlishly but not altogether unfairly spoke of Truman as “a little boy on a toboggan.” The decision had been made for him before he ever assumed command. The would-be Great Man found himself mastered by the onrush of history.

Various other revisionists would amplify Messer’s recital of Truman’s intentions. With Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Americans would end the war without the Soviets grabbing credit for the Allied triumph, prevent them from expanding their empire in the Far East, and deliver a message that the United States now held the whip hand over the excessively ambitious Stalin, who would do well to keep the peace in the post-war world. The decision to bomb was more a warning shot against the Soviets than a final blow to the Japanese. And that made Truman guilty of rank immorality in this consummate act of war that was without military rationale.

Refusing to yield the high ground, the orthodox historians insist on the military legitimacy of the bombing. In answer to the barrage launched against them in the essay collection Hiroshima’s Shadow, the devotees of the conventional narrative refortify their case with an anthology of their own, Hiroshima in History: The Myths of Revisionism (2007), edited by Robert James Maddox. The most unusual and definitive counterattack is the chapter “The Shock of the Atomic Bomb and Japan’s Decision to Surrender — A Reconsideration,” by Sadao Asada, a Japanese historian who was educated at Carleton College and Yale and taught in Kyoto. Rather than focus on American motives, his article concentrates on “the impact of the bomb on Japan’s leaders,” who had to respond to the cataclysm. He shows that the Soviet Union’s declaration of war on August 8 was not the last word on the fate of Japan, and suggestions otherwise by Truman or anyone else were moot. The bombings convinced the Japanese to surrender, without a doubt.

The Japanese literature is scanty due in part to the relative shortage of documents, many of which were burned in anticipation of trials for war crimes. But the chief reason for this lack of scholarship, Asada writes, is “a strong sense of nuclear victimization,” which has made it hard for Japanese historians to “discuss the atomic bombing in the context of ending the Pacific War.” Accordingly, American revisionism has become Japanese orthodoxy. Even Japanese textbooks favor the “atomic diplomacy” thesis, which characterizes Hiroshima as the first strike in the Cold War against the Soviet Union rather than the deciding blow against Japan in the Second World War. Asada quotes what he calls perhaps the most cited Japanese monograph, by Nishijima Ariatsu, which insists that the people of Hiroshima and Nagasaki were “killed as human guinea pigs for the sake of [America’s] anti-Communist, hegemonic policy.” The further left one goes among Japanese historians, as among American ones, the more vituperative they get. “The sense of victimization,” Asada writes, “takes precedence over historical analysis.”

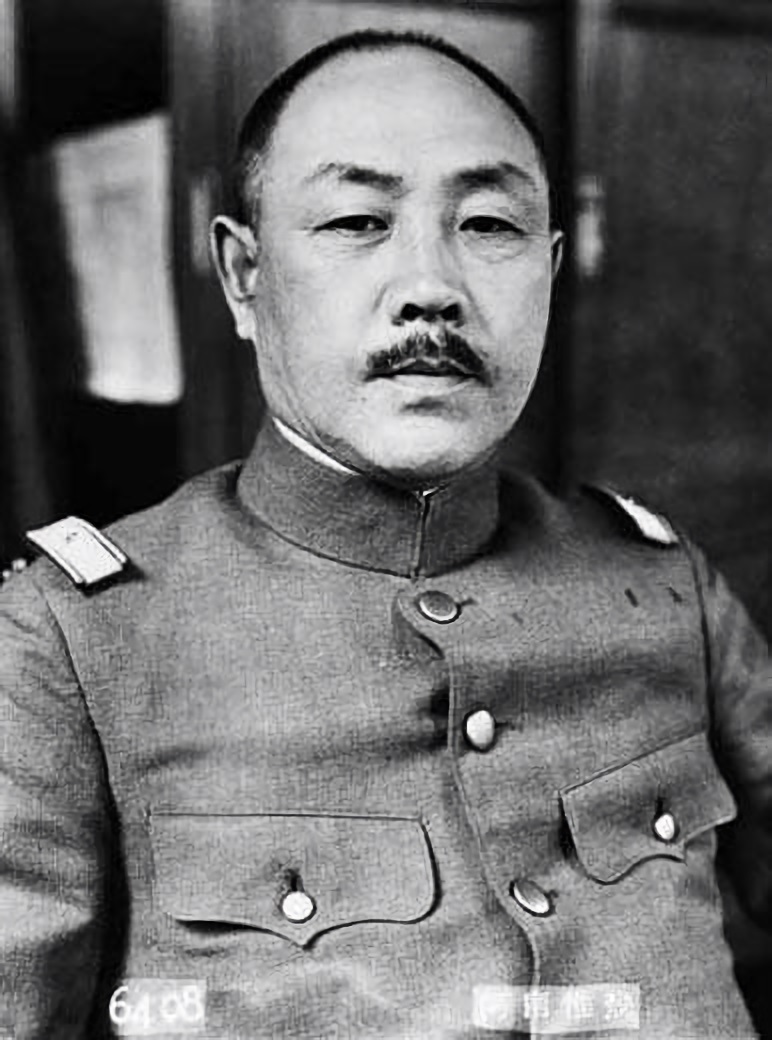

The basic mistake the revisionists make, Asada explains, is to contend that Japan’s defeat was inevitable and obvious as early as 1944, when the capture of Saipan in the Mariana Islands meant B-29s were in range to conduct devastating incendiary raids on Japanese cities, making the atomic bombings unnecessary and incredibly vicious. These historians confuse defeat with surrender: “defeat is a military fait accompli, whereas surrender is the formal acceptance of defeat by the nation’s leaders, an act of decision making.” And the Japanese leadership, specifically three military members of a six-man Supreme War Council advising Emperor Hirohito, would not countenance surrender, even after Nagasaki. Only Hirohito’s unprecedented insertion into the decision-making machinery brought about surrender.

Headed by the Army Minister Anami Korechika, the three military men refused to consider surrender unless their demands were met, including preservation of the imperial lineage, no Allied military occupation, no Allied role in military demobilization, and no Allied prosecution of war criminals. The American revisionists point to the United States’s longstanding insistence on unconditional surrender as a fatal obstacle to peace terms. But, although the Potsdam Declaration of July 26 sharply defined what terms would be unacceptable, it did not forbid the continuation of the imperial descent. A window of possibility opened: perhaps under a constitutional democracy the emperor could still have a role, even if largely ceremonial. The War Council’s other three conditions were non-starters and would not figure in the final terms.

But the War Council initially responded to the Potsdam Declaration with silence. Asada writes that “the consequences were swift and devastating: Japan’s seeming rejection gave the United States the pretext for dropping the atom bomb.” One might more accurately say “legitimate reason” rather than “pretext.” Not even the bombings broke the resolution of the top brass. Anami was refractory to the end, and perhaps out of his mind, declaring even after Nagasaki, “The appearance of the atomic bomb does not spell the end of war…. We are confident about a decisive homeland battle against American forces.” The Chief of the Army General Staff and the Chief of the Navy General Staff still joined him in opposing surrender and deadlocking the council.

Moreover, Asada writes, “fanaticism was not restricted to the military; the men and women in the street were thoroughly indoctrinated. Women practiced how to face American tanks with bamboo spears.” The army for its part was prepared to give the last drop of blood for the cause. Nine hundred thousand soldiers were massed on Kyushu to hurl back the American assault. “In the process, they were to die glorious deaths on the beaches and in the interior — in kamikaze planes as human rockets, in midget submarines as human torpedoes, and in suicide charges by ground units.” Conquest by invasion was bound to be an excruciating bloody slog.

Only when the emperor, a deity disconsolate at the suffering of his subjects and worshippers, broke with his customary role of accepting his advisors’ counsel and made the so-called “sacred decision” to agree to the Potsdam terms was the war brought to a close. “Thus, the atomic bombing was crucial in accelerating the peace process,” Asada writes. Even the Japanese officer corps could eventually accept surrender because Japan was defeated not on the battlefield, but by a technologically unprecedented death blow to the civilian population: face was saved.

Army Minister Anami registered his ultimate protest by committing ritual suicide. In short order, hundreds of his diehard subordinates joined him in this self-butchery for honor’s sake. Likely every last one would have preferred to take as many Americans as possible with him, but on that count they were out of luck.

“Thank God for the Atom Bomb,” Paul Fussell’s 1981 article reprinted in Hiroshima’s Shadow,captures the predominant sentiment of up to a million American soldiers who, like him, would have been consigned to the invasion of Japan and expected to die there. Fussell was already an injured combat veteran of the war against the Nazis when he learned he was to take part in the final battle against Japan. Spared that, he eventually became an English professor and the distinguished author of The Great War and Modern Memory, a study of the literary response to the First World War’s carnage.

The atomic bomb was Fussell’s deliverance. He does not hesitate to say that it was either them or us, and he could not help but rejoice that it was not him and his fellow GIs. Compassion in wartime cuts both ways, and Fussell employs the same sort of sickening and heart-wrenching facts of slaughter as Hersey and company. From such observations he draws a moralizing conclusion about the appropriate course of action, which happens to be the opposite of the revisionist view.

Why delay and allow one more American high school kid to see his own intestines blown out of his body and spread before him in the dirt while he screams and screams when with the new bomb we can end the whole thing just like that?

Any delay in securing the war’s end exacted its toll in suffering and death:

During the time between the dropping of the Nagasaki bomb on August 9 and the actual surrender on the fifteenth, the war pursued its accustomed course: on the twelfth of August eight captured American fliers were executed (heads chopped off); the fifty-first United States submarine, Bonefish, was sunk (all aboard drowned); the destroyer Callaghan went down, the seventieth to be sunk, and the Destroyer Escort Underhill was lost.

God be thanked indeed then, and Harry Truman, and Robert Oppenheimer, and the 130,000 others who took part in the design and manufacture and delivery of the bombs with the slaphappy names Fat Man and Little Boy.

However, divine gifts almost always come with a price, sometimes an extortionate one. Fussell observes in an exchange with the revisionist Michael Walzer that it is a challenge to “come to a clear — by which I mean a complicated — understanding of the moral balance-sheet.” “Walzer says of the bomb-dropping that its purpose was political, not military. I say that its purpose was political and military, sadistic and humanitarian, horrible and welcome.” Fussell understands that no exclusively partisan explanation of the motives for and the morality of the bombing will be adequate. Military and political, the bomb both ended World War Two and demonstrated to a vigilant Stalin what World War Three might look like. So far, this act of atomic diplomacy, admittedly monstrous, has proven its prudence and has sufficiently chastened, not to say terrified, the nuclear powers that they have attempted no further such bombing. Sadistic and humanitarian, horrible and welcome, Hiroshima and Nagasaki not only plunged tens of thousands of innocent non-combatants into an inferno but also spared the lives of innumerable soldiers and civilians alike, American and Japanese.

As intellectuals engaged in political dispute tend to do, the orthodox and the revisionists both place too much faith in their own certainties. They don’t let the truth that the other side presents get in the way of a good argument, and their political passions deflect them from disinterested inquiry that might lead them nearer the center of the labyrinth. If they ever got there, they would find a monster, which no ordinary human can subdue. In this case, the monster would be the inability, for lack of evidence, to answer once and for all the question of why the most destructive weapons ever used were dropped on a couple of unexceptional cities.

What the scrupulous historian is left with is the divided mind of President Truman, farmboy raised on the writings of Plutarch, who wants to be both good and great, and who feels the suffering his decision inflicts on individuals he will never see, even as he weighs the fate of multitudes present and future. When one emerges from the intellectuals’ long wrangling over who did the decent thing and who did not, it is comforting to think that one did not have to make such a weapon or decide whether to use it. God forgive those who did.

Exhausted by science and tech debates that go nowhere?