The first time people in New Orleans truly understood their refrigerators was the summer of 2005, after Hurricane Katrina struck the city. Because big storms are common in New Orleans, families there were accustomed to evacuating for a couple-three days, then coming back to streets covered with branches and trash and maybe a few roof shingles.

Katrina was different — the worst natural disaster in North America in decades. Flooding was so bad that people couldn’t return for two months. And this was New Orleans: sunny and hot. The hurricane had knocked out the electricity. Across the city, 250,000 refrigerators became accidental demonstrations of the biology of putrefaction.

The government warned homeowners not to open their refrigerators. Many did anyway. All realized instantly that something comprehensively bad had happened in their kitchens.

Throughout the fall, returnees duct-taped their refrigerators shut and lugged them out to the curb. White metal boxes lined the streets, painted with do-not-open warnings. Teams of workers in hazmat uniforms slowly loaded them into trucks and drove them to a giant toxic-waste dump in the outskirts of the city. Occasionally people got tired of waiting for the hazmat guys and illegally dumped their refrigerators in faraway neighborhoods only to find when they came home that people from those neighborhoods had dumped refrigerators on their streets.

Thousands of families were discovering that refrigerators are not only appliances: they are also a key component in the public health system. By sealing food into a clean, cold box and constantly filtering the air inside, refrigerators defend families against the legions of bacteria, viruses, molds, insects, fungi, and parasites that otherwise would contaminate their suppers. Suddenly living without refrigerators, Katrina’s victims couldn’t keep their food safe. Emergency rooms filled with food poisoning victims. People in New Orleans were learning the hard way that they could not take for granted one of the pillars of modern life: public health.

Medicine is not the same as public health. The medical system focuses on individuals. The public health system works to safeguard communities. If children get sick from drinking spoiled milk, they go to doctors, who may treat severe cases with antibiotics. That is medicine. The rules setting out how companies treat, store, and package milk, the criteria for how and when it can be sold, the regulations governing the functions of refrigerators, the inspectors that monitor compliance: that is public health.

Public health is generally pictured in terms of doctors and medical researchers setting guidelines for disease prevention and treatment — the kind of actions associated with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Food and Drug Administration. But that’s not how the originators of public health thought of it. Nor does that image adequately describe what they set up — the arrangement we live with now. Built up for more than a century, today’s public health system is a massive, interlocking set of laws, standards, institutions, and technologies that undergirds much of our daily lives.

Paradoxically, the public health system is so omnipresent that its effects are often invisible. But the numbers tell the tale. In 1875, the median age of death in Great Britain, then by many measures the world’s most affluent nation, was 45. Today it is 82. The rise is astonishing. For tens of thousands of years, the average human life expectancy hardly changed. Then, in just 150 years, it almost doubled. The increased food supply created by modern agriculture played a big role in this jump. So did clean water and the electric grid. But the great bulk of the improvement was due to the creation of the public health system.

Its biggest effects were on our smallest. In 1875, about one out of every four British children died before the age of five — 248 out of every 1,000, to be exact. Today the equivalent figure is 4 out of every 1,000, a drop of more than 98 percent. The primary causes of infant and child death at the time were measles, diphtheria, whooping cough, and a host of poorly understood respiratory and gastrointestinal diseases. All were specially targeted by the public health system, mainly through vaccination and sanitation programs. All have been reduced so much that diseases that were common sources of tragedy in 1875 are completely unfamiliar to most parents today.

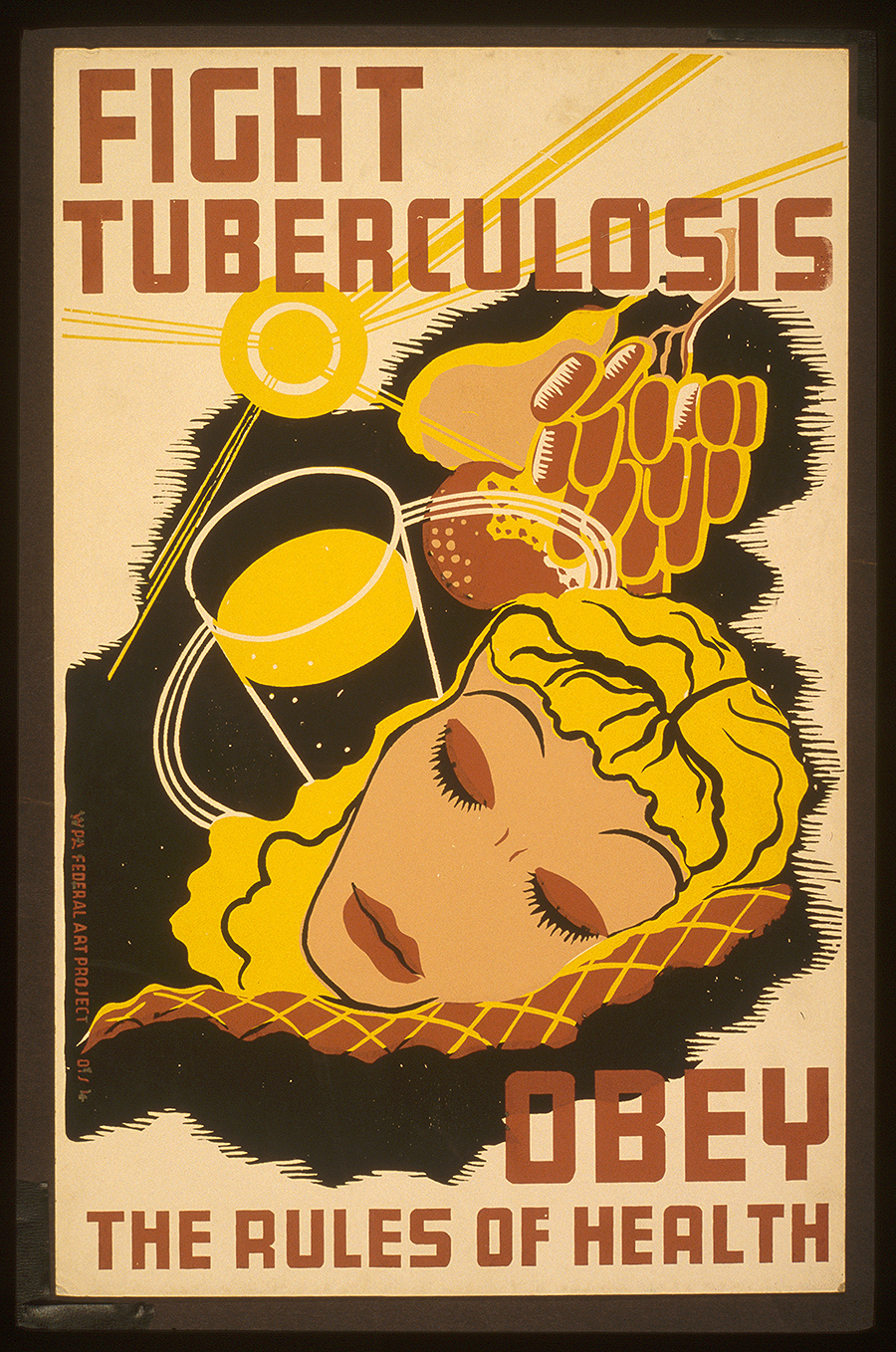

The public health system had many beginnings, but among the most important was tuberculosis. TB, as it is called, attacks the lungs, filling them with fluid and pus. Victims can’t take in oxygen and slowly suffocate, coughing so hard they spit blood. In the nineteenth century, the disease was stunningly widespread. It was the single greatest overall cause of death in the United States, Europe, and Asia — nothing else came close. In crowded places like New York and London, more than nine out of ten inhabitants were infected (though a sizable number had no symptoms). No effective treatment existed. About 70 percent of symptomatic victims died within ten years, and most died within three. TB is thought to have killed a billion or more people in the last two hundred years, more in that time than any other infectious disease.

In 1882, the German microbiologist Robert Koch discovered its cause: Mycobacterium tuberculosis, a group of closely related bacteria. Doctors had believed tuberculosis was a hereditary disease, which meant they could do nothing about it. Koch found that TB instead is due to microorganisms passed from one person to another by coughing, sneezing, or shouting, all of which spray tiny, contagious droplets into the air. People who inhale the droplets suck M. tuberculosis into their lungs, where it wreaks havoc. Galvanized by this discovery, volunteers created hundreds of anti-tuberculosis associations across the United States that sought to stop M. tuberculosis from spreading — and launched, along the way, today’s public health system.

Some of the reformers’ ideas were off-base, such as their campaigns to abolish floor-length dresses (thought to pick up deadly bacteria from the ground) and beards (seen as bacterial time-bombs on men’s faces). Others are now so widely accepted that it is hard to believe that anyone had to advocate them. Among these are the notions that people should cover their mouths when they sneeze, wash their hands after visiting the toilet, and not spit on the floor or sidewalk.

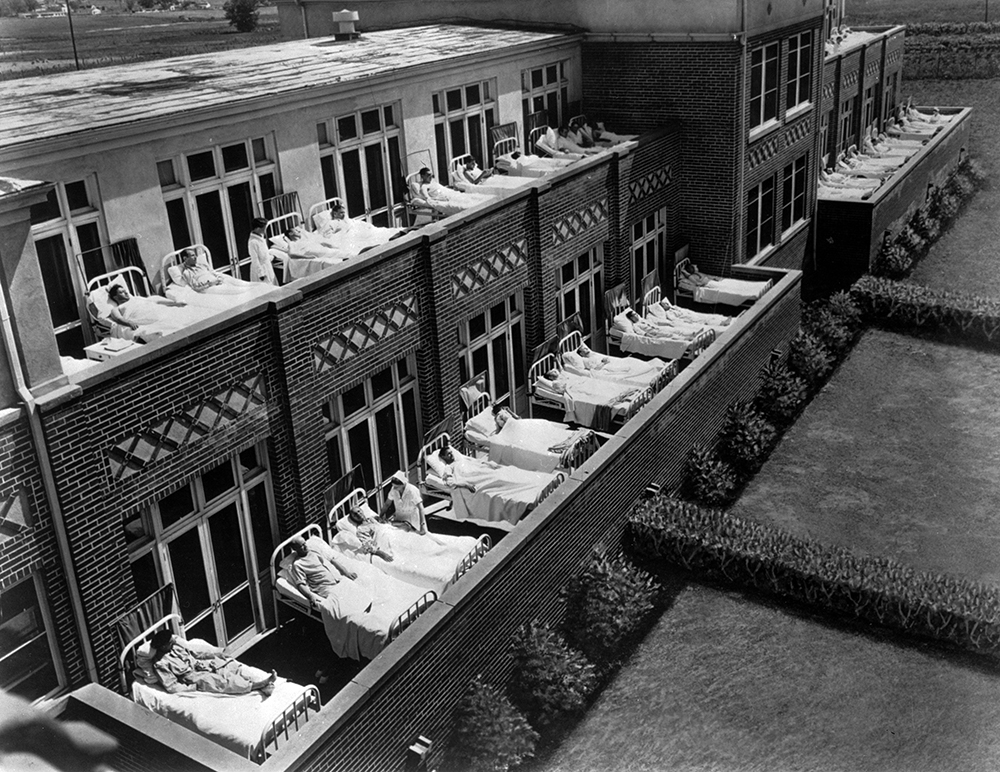

All the while, the TB associations were establishing a novel infrastructure of health: hundreds of new TB dispensaries, TB open-air tent camps, and TB sanatoria (specialized hospitals for long-term care). The dispensaries were information centers where technicians diagnosed TB cases and shunted patients to camps (if the case was mild) or sanatoria (if it was severe). The camps and sanatoria served two main functions. The first was a kind of quarantine. By packing TB sufferers into dedicated facilities, the reformers prevented them from infecting others. The second was to provide rest, sunshine, fresh air, and a balanced diet: improved living conditions that would, activists hoped, let TB patients get better by themselves. Mostly, these treatments had little impact. The first real cure for M. tuberculosis was an antibiotic, streptomycin, proven effective against tuberculosis in 1944. But the camps and sanatoria represented the first systematic, nationwide effort to provide a clean environment to improve health.

Coupled with these measures was a raft of new laws and regulations. In the early twentieth century, for example, many urbanites got water from municipal water pumps, drinking from metal cups that hung by the pump handle. Similarly, conductors carried buckets of water on trains, offering drinks to passengers from a common cup. Reformers denounced the cups as vehicles for transmitting M. tuberculosis, and by 1912 they had convinced 24 states to ban them at drinking fountains and the federal government to restrict them on interstate railways. In addition, they had managed to pass 150 urban anti-spitting laws, though apparently these were lightly enforced.

The anti-TB effort set the template for other, later medical campaigns, such as those against hookworm (a parasite that then infected more than a third of the people in the southeast) and typhoid (a disease caused by a lethal variant of salmonella that at the time was rampant in American cities). More importantly, the effort was a launchpad for what became a broader movement to improve Americans’ physical and mental well-being.

In 1904, the Charity Organization Society, an umbrella group for the nation’s numerous private philanthropical organizations, argued that controlling tuberculosis would require not only direct medical interventions but “public sanitary preventive measures in street and shop and home.” The idea was that the rise of industrialized societies, with their dangerous factories and dirty cities, was fostering the conditions for not only tuberculosis and other infectious diseases but also unsafe foods, deadly accidents, and dying children. And those industrialized societies were so complex and operated on such a grand scale that it was folly to imagine that people could overcome these problems individually; governments and large institutions had to step in. Eventually businesspeople, politicians, doctors, economists, and muckraking journalists joined what would become a crusade to increase the safety and salubriousness of American life.

The ensuing reforms created an enormous system that, in theory, can be thought of as covering four main areas:

In practice, the public health system is an overwhelming pile-up of rules and procedures that affect everything from the packaging of milk to the contour of highway curves, from the standards for electric plugs to the performance of automobile bumpers, from noise limits in factories to air conditioning norms in offices, from apartment fire safety requirements to water testing guidelines for sewage plants. Local statutes regulating the design of sidewalks to protect pedestrians from cars, state vaccination mandates to protect children from disease, nationwide environmental laws to protect citizens from dirty air and water: the public health system encompasses them all. It sets down how chlorine must be administered to swimming pools and fluoride to drinking water. How children’s playgrounds in many states must have a foot of impact-absorbing material (wood chips, safety-tested rubber) around each piece of equipment. How construction workers must don protective equipment like respirators, hardhats, and safety glasses. How coaches, pharmacists, electricians, park rangers, and veterinary technicians must be trained in cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR), a technique for restarting a person’s heartbeat after it has stopped. And so on. And so on.

The immense network of health regulations is administered by an equally large network of state, local, and federal agencies. The Occupational Safety and Health Administration, the Health Resources and Services Administration, the Federal Occupational Health, the Administration on Aging, the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, the Food and Drug Administration, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the Environmental Protection Agency, the National Institutes of Health, the fifty state and thousands of municipal health departments — a full list would take many pages.

Much of the information used to lay out these rules is contained in the 86 volumes of ASTM standards, most of them fat black paperbacks. (ASTM initially stood for American Society for Testing and Materials, but the organization now calls itself simply ASTM International.) Generated by countless research teams over more than a century, ASTM standards are the results of testing the safety and performance of a staggering variety of materials in an equally staggering variety of circumstances. To glance at their titles is to reveal the intricate, far-reaching way these standards are woven into the world we have built around us.

These are supplemented by still more standards from specialized groups supervised by the American National Standards Institute, which also coordinates with two major international standards organizations, the International Electrotechnical Commission and the International Organization for Standardization (known as ISO). They, too, have their own libraries. Taken together, these tens of thousands of documents are the warp and woof of the public health network. If somehow society collapsed, these bodies’ collective works are the texts one would need to rebuild it.

At the same time, many public health measures are contentious. Almost all public health measures involve imposing some costs, in part or in whole, on individuals or groups to benefit a larger community. Frequently the costs are small. When regulations force restaurant waiters and cooks to wash their hands after visiting the bathroom, few of those businesses or employees complain — the cost in water, soap, and time is minimal. Similarly, not many objections were raised when the 1971 edition of the National Electrical Code required that standard electric sockets in new homes be grounded — that is, have a three-prong socket — so that people wouldn’t shock themselves replacing light bulbs or experience fires from short-circuits. Some contractors grumbled about the extra work of putting in ground wires; some consumers were annoyed when they had to buy adapters to resolve a mismatch between old, two-prong sockets and new, three-prong plugs. But overall, the changeover happened smoothly.

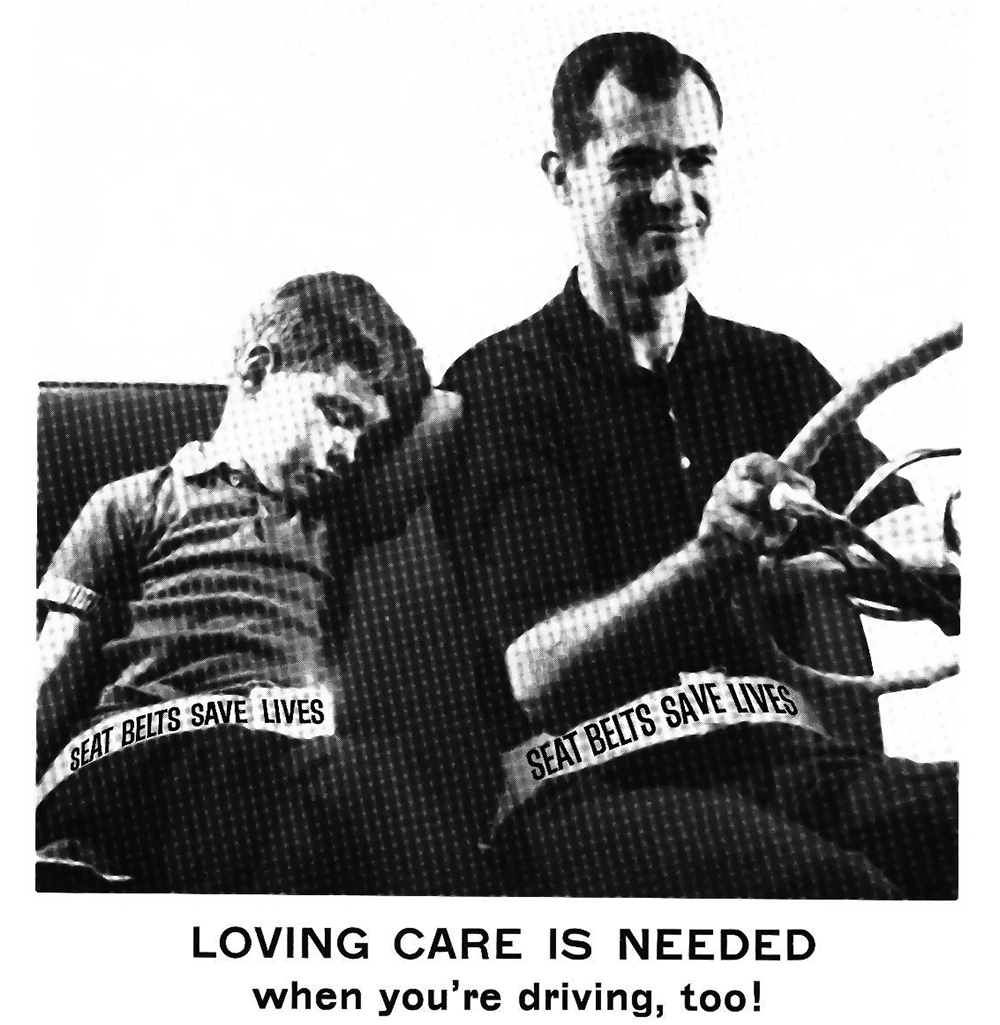

On another level, people now generally want cars to have safety features like seat belts, air bags, crash-resistant bumpers, and pollution controls. But they didn’t always. So many drivers were angered in the 1970s by the first mandates requiring them to use seat belts that Congress repealed the rules. In a surprise, the Supreme Court reinstated them. The automobile companies supported the ruling — but only because they hoped that seat belt directives would be enough to stop health-and-safety regulators from demanding they also put air bags into new cars. (The hope didn’t pan out.) Even today, when seat belts and air bags are more accepted, those safety features are not free. Studies show that safety regulations have, over the last half-century, built up to the point where compliance accounts for nearly $3,000 of the cost of a new car in today’s dollars.

Opposition to public health measures is most intense when large numbers of individuals are asked to accept a personal risk to benefit the community, especially when the risk is imposed by “experts” whom those individuals don’t trust.

In 1918, a lethal influenza pandemic swept the world. At least 50 million died, equivalent to about 225 million today when adjusted to the current population. (By contrast, Covid killed 25 to 30 million.) As hospitals and morgues filled up, many U.S. cities passed laws decreeing that everyone had to wear a face mask in public. Nobody then knew the cause of what was called the “Spanish flu” — the virus that causes influenza wasn’t discovered until 1931. But medical reformers, the experts of the day, were sure that this disease, like tuberculosis, spread through the air.

Public resistance was immediate and vehement. Mask mandates struck more than a few Americans as dictatorial interference in private life. Many city dwellers viewed streets filled with masked people as threatening and alienating. In San Francisco, a center of resistance, a health inspector shot an anti-mask activist in a violent tussle. Soon after, a bomb was defused in the quarters of the city health officer. A wealthy San Francisco socialite founded the Anti-Mask League, which staged demonstrations before the city’s Board of Supervisors. “Freedom and liberty!” protesters shouted.

Similar ire greeted the cities that added fluoride to their water supplies. Throughout most of our species’ history, people have spent much of their lives with rotting teeth. Famously, George Washington had only one tooth in his head when he was sworn in as president. To make his smile presentable, he wore sets of false teeth made from real human and animal teeth. The introduction of sugar to diets in the nineteenth century worsened our nation’s dental issues. To enlist in the U.S. Army in the early 1940s, G.I.’s were required to have at least twelve opposing teeth: six on the top, six on the bottom. Thousands of would-be soldiers were barred from service in the Second World War because they didn’t have even twelve opposing teeth.

In the 1930s, dentists discovered that people in Colorado had fewer cavities if the water in their wells contained chemical compounds called “fluorides.” Within twenty years, cities had begun experimenting with tipping small amounts of fluoride into their water supplies. In every case, overall dental health improved. In reaction, an anti-fluoridation movement emerged: a loose coalition of chiropractors, biochemists, homeopaths, Christian Scientists, Boston society ladies, and Dr. E. H. Bronner, the spiritualist soap-maker. They feared that fluoride would be deadly — fluorine, its main constituent, is lethal even in small doses. And they didn’t trust the experts who promised them that it was safe to put a toxic substance in their drinking water. Congress held hearings on the subject, at one of which a San Francisco woman testified that fluoridation was a Communist plot to turn Americans into a race of “moronic, atheistic slaves.”

The anti-fluoride crusade never vanished entirely. Possibly spurred by a study in January that found 2 million Americans live in areas with fluoride levels high enough to lower children’s IQ scores by a small but detectable amount, the Utah legislature banned fluoride in public water systems in May. And Health and Human Services head Robert F. Kennedy, Jr. has talked of trying to ban fluoridation nationwide (though his agency probably doesn’t have the authority to do that). Nonetheless, the anti-fluoride crusade is a shadow of what it once was.

The same cannot be said for the anti-vaccination crusade. Vaccination and vaccination-like measures have been known for centuries in parts of Asia and Africa. But they were unknown in Europe and the United States until the early eighteenth century. The first tests drew controversy — one that has never, it seems fair to say, gone away.

In contemporary terms, vaccination involves “training” the body’s immune system to attack a bacterium or virus by exposing it to less-potent forms of those microorganisms. In general, it makes people better equipped to fight off diseases themselves. But vaccination can’t fully protect all people. Inevitably, some will have immune systems that don’t “train” well. These include cancer patients, children too young to have fully developed biological defenses, and pregnant women (although the fear for them is more that the shot might affect the fetus than that it would harm the woman herself). But those people can be protected by a second effect of vaccination: what is called, perhaps unfortunately, “herd immunity.” If a sufficiently high proportion of the members of a community are vaccinated, bacteria and viruses can’t find suitable hosts. In “herd immunity,” the vaccinated form a protective wall, so to speak, around the unvaccinated.

For vaccine critics, the main problem with vaccination is that it involves injecting healthy people with a disease (or, in some cases, putatively risky chemicals added to vaccines as preservatives or to enhance their effects). Even with modern methods, there is a tiny but real chance that something could go wrong — people occasionally react badly to vaccines. When parents take their children to be vaccinated, they are unavoidably exposing their children to a risk (again, a very small one). For this reason, Congress set up the National Vaccine Injury Compensation Program, which awards money to children and adults injured by vaccines. Between 2006 and 2022, for example, the U.S. dispensed 2.4 billion flu vaccine shots. About 6,600 people — less than three ten-thousandths of the total — had reactions severe enough to be compensated by the fund.

That number is minute, but it is not zero. On an individual level, parents would be smart to avoid vaccinating their children and rely instead on herd immunity — letting others take the hit, so to speak. But if everyone did this, there would be no herd immunity. Since 1855, states have responded to this problem by decreeing that children must be vaccinated to attend public school. And since that time, protesters have charged that the government has no right to force them to endanger their children. Only in 1905 did the U.S. Supreme Court uphold the legality of compulsory vaccination. The Constitution, the Court said, “does not import an absolute right in each person to be … wholly freed from restraint.” Otherwise, it said, “organized society could not exist with safety to its members.”

The Supreme Court ruling didn’t stop anti-vaccine protesters. Nor did similar rulings stop those protesting mask mandates and shutdowns during Covid. Or anti-smoking ordinances, when those were first passed. Or motorcycle helmet laws, when those were first passed. In every case, the underlying issue was the same: How much of an infringement on personal liberty is permissible to benefit the public as a whole? How big must that communal benefit be to justify the cost to individuals?

In the fights over Covid, public health advocates often argued that one should “trust the science.” But many of these questions, then and now, are not fundamentally about science. During Covid, many areas closed schools for prolonged periods, fearing that children in crowded classrooms would spread the disease among themselves, and from them to parents and teachers. School lockdowns surely saved some lives. But with equal surety they harmed students’ educations and social skills, with the effects being especially dire for children who are from poor families or had learning disabilities. In addition, not letting children go to school made parents’ lives more difficult in a terrible time. In retrospect, were the closures a mistake? How should we balance all the competing interests in making decisions about the health of communities?

Such questions will come up again and again as the public health system is faced with new circumstances and new knowledge. And because the answers to those questions will be informed by our priorities, which shift as our circumstances shift, they will have to be renegotiated by each generation. No one can say now what the best answers will be in the future. But a vital necessity for maintaining the public health system that reflects our values tomorrow will be having some understanding of what the system is now, and how and why it was created by our forebears.