It’s the ninth inning of a decisive Major League Baseball playoff game. The San Diego Padres have just cut into the lead of the Chicago Cubs with a home run, and shortstop Xander Bogaerts has a count of 3 balls and 2 strikes. The next pitch looks low and outside, and the disciplined Bogaerts does not chase it. He starts toward first base. But the umpire calls it a strike. Bogaerts slams the butt of his bat down in the dirt and faces up to the umpire. He’s certain it was a bad call, at a consequential point in the game. It ended what looked like his team’s season-turning rally.

But no amount of arguing changes an umpire’s call. Bogaerts told reporters afterwards that the call “messed up the whole game…. Thank God for ABS next year because this is terrible.” ABS stands for Automated Ball-Strike System, a sort of digital umpire. ABS uses Hawk-Eye, a computer vision and data collection technology that, among other things, tracks ball movement and location. In 2026, Major League Baseball will use the technology to give each team two challenges per game of an umpire’s call of ball or strike. If the challenge is successful — meaning the umpire is wrong according to the technology — then the team retains the challenge. Only the batter, the catcher, and the pitcher can issue a challenge.

Rob Manfred, the Commissioner of MLB, has touted the system as an improvement in the game for the sake of fan enjoyment. It is true that bad calls frustrate fans. Consider some of the comments on the YouTube video of the Bogaerts strikeout:

I’m so sick of bad calls by umpires. And it’s the playoffs man. Shouldn’t happen.

Can’t wait for the ABS challenge system next year. No matter who you root for, you should want the game to be as fair as possible. This was a great take from Bogaerts but the ump robbed him. Next year that won’t happen.

These are the types of calls that are killing the game of baseball. That wasn’t even close.

The issue is widely seen as a matter of integrity and fairness in the game, which the human umpire is accused of undermining. Or, as one commenter put it, “pitch framing” — when the catcher tries to make a bad pitch look better by catching it in a strategic way — “is the second best argument for robo umps. The best argument is the actual human umps.”

According to MLB’s own calculations, plate umpires make the right call up to 98 percent of the time. For years the league has evaluated and graded umpires on the accuracy of their calls using the same type of technology that will now be used for challenging them. The ABS system simply formalizes what has long been the case: we believe that only the machine should ultimately be trusted with calling balls and strikes. Human judgment is effectively out of the loop. If you want to question the machine — well, how could you?

There are few performances in sports outside of the actual gameplay more entertaining than a manager and an umpire face-to-face screaming at each other. It is made more elegant by the soundlessness of the encounter for those watching on television. Were it not for the unmistakable looks of rage, one might think they were moments away from a warm embrace. And when they part, the game goes on.

Bobby Cox is the all-time leader in Major League Baseball ejections, having been thrown out of the game 162 times. That is the equivalent of an entire season of ejections over his more than thirty seasons as a manager for the Braves and the Blue Jays. Most ejections were for arguing a call made by an umpire. Not once did his arguing result in changing the umpire’s decision.

The call of an umpire has always been incontestable. There is no appeal process. So why do players and managers argue with umpires? I expect that it is in the hope that the umpire sees the expression of grievances as constructive advice for improvement. There might be some gameplay to the non-gameplay here, in the sense that teams see umpires repeatedly throughout the year, so maybe they hope that aggressively informing them of their errors might lessen the errors later in the season. Or, more likely, the whole performance is an emotional outburst, a way of signaling to everyone — players, coaches, fans, the other team — just how much it matters that the umpire gets the calls right (in one’s favor, of course).

The MLB implementation of ABS will serve as an appeal system of the umpires’ decisions. For the first time in the long history of baseball, players can contest the call of ball or strike with the possibility of changing the umpire’s decision.

But it is very possible that the appeal system itself is a passing phase in baseball’s journey to robo-umps. ABS was initially used in the lower division Atlantic League starting in 2019, where it was used as a full system. Every call was determined by the technology, and the umpire was just a mouthpiece for the computer’s determination. MLB Commissioner Manfred has described the Atlantic League implementation of ABS as an experiment to give the technology time to improve. The other reason, one might surmise, was to test its acceptance in games with low stakes but reasonable fan engagement. The implementation of ABS in the Major League is what Manfred calls an “intermediate step.” Speaking on the Dan Patrick Show in September, Manfred said the challenge system would keep the “human element” in the game and allow the homeplate umpires to keep their “management role.” But the 2026 season will itself be an experiment, and the prospect of going “the whole way” — of making the umpire just a mouthpiece of the computer’s determinations — is a real possibility.

In time, teams and players may find the restrictions of the challenge system unnecessary. If machine vision gives unmistakable results, why keep the challenge system? It seems only a matter of time until a team has exhausted its challenges and an errant call late in a critical game goes unchanged. Then people will wonder: Why bother with plate umpires’ judgments at all? One need only look at tennis, which is two decades ahead of baseball in the use of Hawk-Eye technology at the top level. In tennis, what started as a challenge system evolved into a system that has replaced line judges in major tournaments.

When Xander Bogaerts thanked God for the arrival of ABS in the 2026 season, he probably did not mean to suggest anything about absolute authority. Nevertheless, in replacing the excellent but flawed judgment of human umpires with machine vision, Bogaerts’s gratitude to God testifies to a deep willingness to submit to an authority that is unquestionable. The umpire, being human and fallible, can be doubted, but the machine offers only evidence of its decision without recourse to any human dispute. The social energy that Bobby Cox added to a game when he charged out from the dugout to scream his objections at the umpire might still happen, but the umpires will have no response other than to shrug and point to their earpiece that delivers the computer’s call. All the passion you can muster will be absorbed by the radical and incontestable neutrality of the machine.

To really understand the incontestability of the machine decision, one must recognize that the data used to calculate the trajectory of the ball is outside of human ability to judge. Humans cannot check the system. In baseball, the Hawk-Eye system uses twelve cameras that capture hundreds of images per second. Five of the cameras are engaged directly with pitching and can capture release angle, spin rate and axis, velocity, and movement. These images are then triangulated according to the cameras’ positions to create a three-dimensional position of the ball in space and produce a single trajectory of the ball as it crosses home plate. It is an elaborate system of data collection and processing.

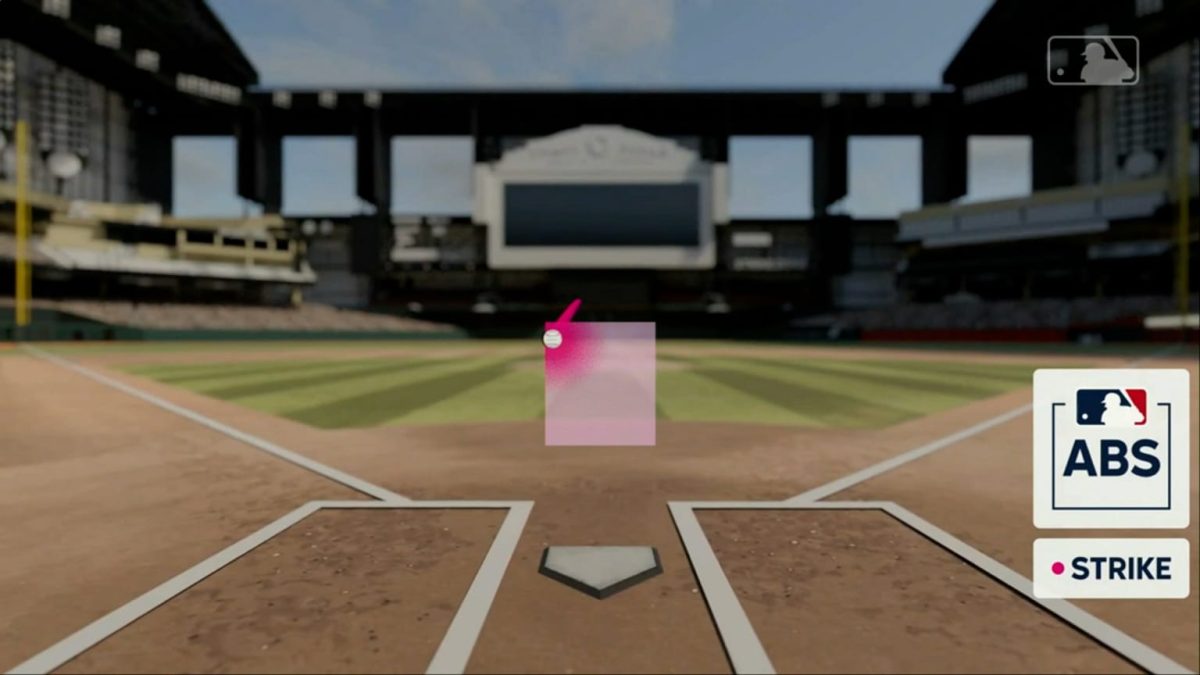

When a challenge is made, the computer produces a rendering of the ball crossing the plate with a rectangle image superimposed as the batter’s strike zone. What is shown to viewers is an animation based on the data, not an actual image. The computer essentially shows a video of the decision it has already made. There is no way to counter the computer or check its decision, no appeal on the basis of other evidence. No human can see as the computer sees.

The irony of the situation is that in the interest of checking the authority of the umpire, who was the final decision for more than a century, the solution turns on another indisputable authority, but now it is a machine. And who can disagree with a machine that sees hundreds of images per second across multiple vision points?

Of course, those disagreements won’t fully go away. We all know machines aren’t perfect. But the issue turns on what it means to disagree with a computer operating with data and speeds outside of human ability and cognition. The passionate outburst directed at an umpire was understandable because the umpire is a fallible human, and we can dispute human fallibility. But with computer vision, there is nobody to blame.

There is a video of a seemingly bad strike-three call by ABS that captures the strange experience of disagreeing with the decision of the machine. In a 2021 Atlantic League game between the Lexington Legends and the Lancaster Barnstormers, a Lexington batter watches as a pitch seems to sail well outside the strike zone. He calmly starts to reset his stance when the umpire calls strike three. The batter drops his bat and bends over with his hands on his knees. He removes his helmet and then turns to speak to the umpire. If you watch closely, you see the umpire just give a subtle shrug, as if to say that it is out of his hands, which is exactly what the game announcers say: he’s “just getting the signal from above.” The voiceover of the person from Close Call Sports who posted the video expresses the state of confusion well: “That’s kind of not a strike, except robo-ump says it is, so it must be. Right?” The batter then walks to the dugout, his face not one of anger but of resignation. Before ABS, he would have felt a sense of indignation at the bad call. With ABS, his indignation has no target. The signals are just coming from above.

This seemingly bad call happened more than four years ago, and many involved in the implementation of ABS at that time agreed the system needed improvement. Since then, it has only gotten more accurate. According to Manfred, its margin of error has shrunk from two inches ten years ago to about a hundredth of an inch. It has become more incontestable.

When you replace human judgment with computer vision, players will no longer rage against a bad call but despair at it. How can we expect to evaluate a system like ABS, to evaluate the evaluator, when human ability has been judged inferior? There will be no way to know if the machine is right except by employing yet more formidable technology to test it. Using our human faculties we cannot know what is right.

Perhaps that is the comfort we have been seeking all along, a resignation to an indisputable machine: Thank God for ABS.

Keep reading our

Winter 2026 issue

Dinergoths • Empty cities • Obesity wars • Killing sports • Subscribe

Exhausted by science and tech debates that go nowhere?