With the election of Senator Barack Obama as the next president, a renewed and serious debate about covering the uninsured in the coming years seems certain.

There will be much to discuss, course: The merits of “pay or play.” Enforcement of individual mandates. Insurance market reforms. And much, much more.

But perhaps no issue is as potentially volatile as what to do about uninsured immigrants. It’s no small matter, as a recent analysis [PDF format] from the Employee Benefit Research Institute (EBRI) makes clear.

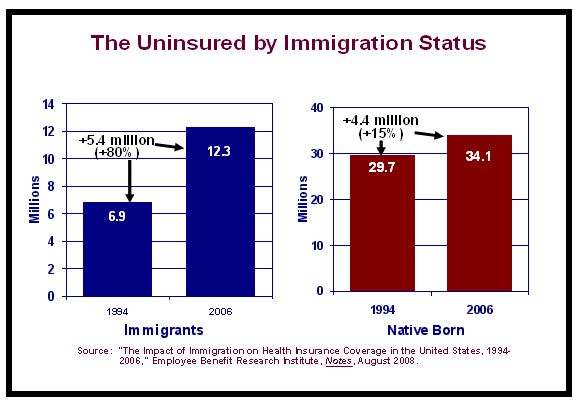

According EBRI, the number of uninsured residents in the United States under the age of 65 increased from 36.5 million in 1994 to 46.5 million in 2006, an increase of 10 million people. Of this increase, 55 percent, or about 5.4 million people, were immigrants — that is, foreign-born persons (citizens and non-citizens) residing in the United States. An indeterminate number of the non-citizen uninsured are here illegally.

In 1994, there were 6.9 million people in the United States who were immigrants and uninsured. In 2006, the number of immigrants without health insurance had grown to 12.3 million people, an increase of 80 percent in a dozen years. By contrast, the number of native-born uninsured in the U.S. was 34.1 million in 2006 — just 15 percent more than in 1994 (see the chart below).

Uninsured immigrants are highly concentrated in a handful of states. On average, there were about 11.7 million uninsured immigrants in the United States over the three-year period 2004 to 2006. Of that total, 60 percent lived in just four states: California, Texas, Florida, and New York.

The 1996 welfare reform law has had a major impact on the number of uninsured immigrants. The 1996 law placed new restrictions on enrollment in Medicaid by non-citizens. New immigrants are now required to wait five years before they can apply for public insurance coverage, and even then they may not qualify as easily as before because new rules assume an immigrant is getting income support from their sponsor. This change is reflected in the statistics: Between 1994 and 1998, immigrants accounted for 43 percent of the increase in the uninsured; between 1998 and 2003, they accounted for over 90 percent of the increase in the number of uninsured.

EBRI’s analysis shows that the probability that an immigrant will remain uninsured drops precipitously with time. For foreign-born non-citizens, the probability of being uninsured is nearly 50 percent if they arrived in the United States after 1999, but only 27 percent if they arrived before 1970.

Immigrants who become U.S. citizens are only slightly more likely to be uninsured than citizens. EBRI estimates that the uninsured rate among foreign-born citizens is about 20 percent for the under-65 population, compared to 15 percent for native citizens under age 65.

Health care reform — already complex politically and substantively — will become even more so when more Americans become aware (as they surely will) of the potential implications of some reform plans for immigration policy. When that time arrives, proponents of reform will need to be ready with a politically-defensible position — or the entire effort could be in jeopardy.

The full EBRI analysis is available in their August 2008 edition of Notes, available here.