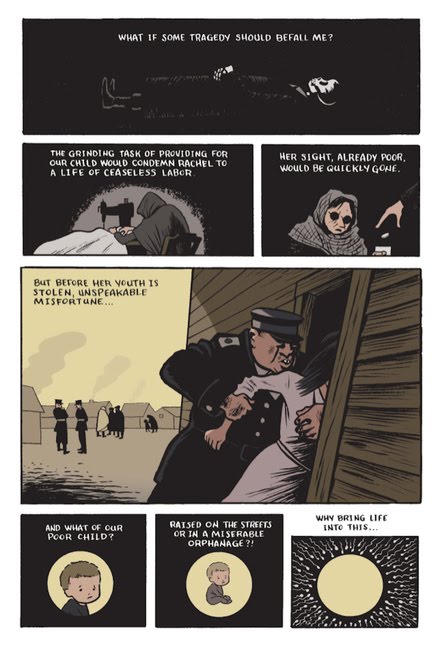

To me, James Sturm’s Market Day provides a far more compelling visual world than David Small’s Stitches. It is beautiful and memorable. But even so, the story leaves something to be desired. Sturm tells the story of a rug-weaver who takes his wares to market but by the end of the day has, it seems, completely changed his life. The problem is that there just aren’t enough . . . well, words to explain this change. There’s no doubt that Mendelman suffers some serious jolts during what he had expected to be a commonplace visit to a nearby market town, but are those jolts really sufficient to cause him to throw over his life’s work, his beloved vocation? Would any man so dedicated make so dramatic a decision so quickly? It’s not impossible — but it’s not at all likely. We need to learn more about Mendelman in order to decide whether his catastrophe makes sense. I think we also need more background, in Mendelman’s character and in the culture, to account for the descent into obscenity that he suffers near the end of the story.

There are some things pictures do better than words: Sturm creates with remarkable power the materiality of the old world of Eastern European Jewish culture. But other things words do better than pictures: Mendelman’s delicate psychological state is something that can’t be rendered fully and effectively without more language. Or so it seems to me.

It’s a very worthwhile book all the same. I want to emphasize that in case he sees this, because he told Amazon that he started his recent internet fast in part because of his responses to (amateur and professional) reviews:

In some ways, Market Day was the reason I went offline. I can get obsessive sometimes when I’m online, and I knew if I had a book out, I’d be looking at my Amazon ranking, and I’d be re- reading interviews, and, you know, “What does Chewbacca45 think of my book?” Like Mendleman, every one of those things would be either an ego puff, or a little arrow. As I’ve gotten older and done a few books now, I’ve realized how fleeting this moment is…and by not being online, I feel like I can enjoy this very brief window. I feel like I have a healthier relationship with the book.

Text Patterns

June 23, 2010

"There are some things pictures do better than words: Sturm creates with remarkable power the materiality of the old world of Eastern European Jewish culture. But other things words do better than pictures: Mendelman's delicate psychological state is something that can't be rendered fully and effectively without more language. Or so it seems to me."

Several years ago, as I tried to understand why the world was full of excellent examples of written erotic sexual encounters; but virtually bereft of excellent examples of filmed erotic sexual encounter I stumbled across the realization that much of what makes the sex act so pleasurable is hidden from view, either physicially hidden, or is simply not something the camera can see; and that nearly filmed depictions attempted to reveal these hidden treasure either by distorting the physical act with unlikely or even uncomfortable postures, or by having the players give voice to their interior thoughts with awkward utterances.

By contrast, the conventions of writing allows unfettered access to characters most private thoughts; and if this is accomplish by distortions, (I've always found it odd that an author is permitted inside his characters' heads, and doubly odd he is permitted to reveal the secrets he find there) they are distortions that are completely taken for granted in the medium.

As I said in on the previous post, I don't do comic books. I have a hard enough time reading conventionally formatted text; I think the scatter-shot layout in comics, absent cues for what order to read in hits my brain like a busting covey of quail.

But I also notice the close-ups in comic are just too "on the nose" for me. Those sort of close-ups are one of the ways a filmmaker can get inside a character's head, but they're delicate. Lear too long or too hard and the audience is left thinking "Okay, I get it already." As with the text, I don't seem to pick up the cues on how long I should look at what panel, and it all end up coming across to me as obvious and/or flat.

Of course me accusing any one, let alone any genre of being unsubtle is pretty rich. I think that's at least part of what Popper was talking about in that quote at TAS.