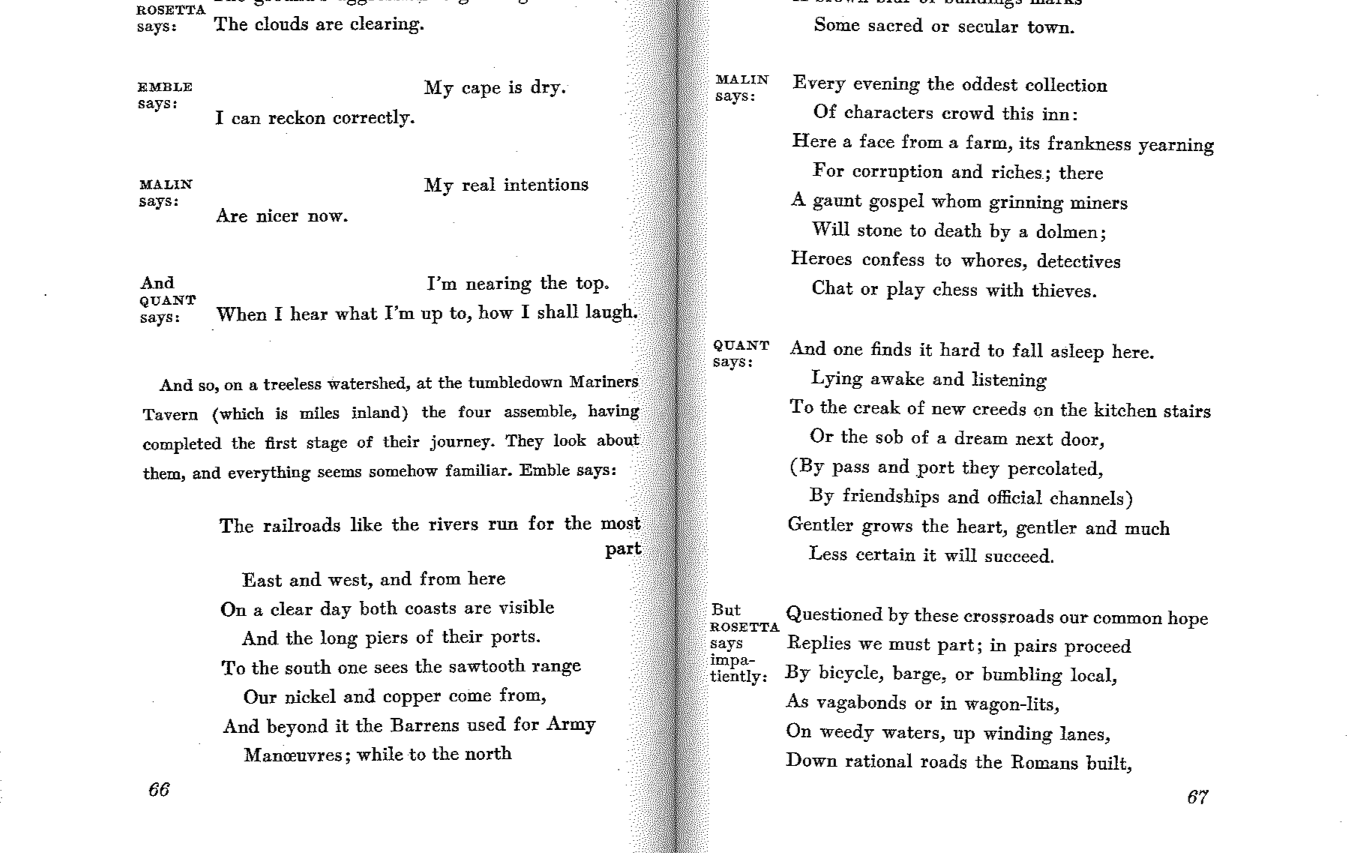

Here’s a really thoughtful post by Siobhan Phillips on the highly fraught relationship between e-readers and verse. Phillips wants to argue that poetry’s concern with lineation and space ought to cause us to rethink what books and texts are. Poetry is not just a problem for e-reading, but a challenge to us to reconsider what we think is intrinsic, and what extrinsic, to a text, especially a literary text.I was thinking along similar lines when I was working on Auden’s Age of Anxiety, because Auden was so concerned about the appearance of his work on the page. He frequently quarreled with his American publisher, Random House, about the appearance of his books. “It isn’t that I don’t realise that, as such things go, the fount [font] is well designed,” he wrote to Bennett Cerf in 1944. “It’s a matter of principle. You would never think of using such a fount for, say, ‘The Embryology of the Elasmobranch Liver’, so why use it for poetry? I feel very strongly that ‘aesthetic’ books should not be put in a special class.” And then, in 1951, he told Publishers Weekly, “I have a violent prejudice against arty paper and printing which is too often considered fitting for unsalable prestige books, and by inverted snobbery I favor the shiny white paper and format of the textbook. Further, perhaps because I am near-sighted and hold the page nearer my nose than is normal, I have a strong preference for small type.” Nick Jenkins, a wonderful Auden scholar, has written: “In 1946, when he told Random House what he wanted for The Age of Anxiety, he loaned them his copy of A Treatise on a Section of the Strata from Newcastle-upon-Tyne to Cross Fell, with Remarks on Mineral Veins, by Westgarth Forster, a book originally published in 1821 but that he seems to have owned in the third edition of 1883, and instructed them to copy its appearance. They did. A Treatise on a Section of the Strata had been set in Scotch, an extremely popular 19th century typeface, and the Kingsport Press in Tennessee used the Linotype version of Scotch for Auden’s book.” (We couldn’t use it for our edition, though.)

Alan,

Have you seen a website or other electronic format that handles poetry well? I struggle with reading poetry on electronic devices, partly because of issues of space, typesetting, etc., and partly because of the distracted/ing nature of electronic reading. How is reading poetry on the Kindle?

How is reading poetry on the Kindle?

Terrible! (Siobhan Phillips's article discusses the problems.)

You should see Esolen's translation of the Purgatorio on the Kindle. The English and the Italian run together in parts, the notes are all at the end of the Canto.

Thanks for this great discussion! Auden is just one of many poets with whom I would love to discuss the possibilities of digital presentation. (Merrill, for instance: what are the thirty-years-on equivalents of the letter and caps and characters of *Sandover*). It's consistently remarkable how many poets of the 20th century (and even before) were highly concerned with their type and paper. Makes me wonder if some sort of programming/web design interest is flourishing or will flourish among poets? (I wish I knew more, certainly, about these fields, with regard to imagining the possibilities….)

Oh, and yes: notes. Another challenge–which screen reading should make *easier,* but which often becomes harder in the transition from print to screen. I think good fixes for that have to be just a matter of time….

Siobhan, you're right that Merrill would be a great test case. And I remember at one point thinking how cool it would be to have an annotated online version of Pound's Cantos — and then I remembered how difficult it is to do a simple paragraph indentation in HTML, and looked again at the highly variable indents of Pound's lines, and . . . fuggedaboudit.

When I think about how much trouble Edward Mendelson and the production editors at Princeton and I have had trying to get the verse of The Age of Anxiety rightly spaced on the page, and then think about the difficulties of digital presentation, I wonder how long it's going to be before we have the tools to do this right. But it would seem, per your suggestion, that poets are probably going to need to learn to think about these matters in the coming years. Are y'all ready?

Alan, that's a lovely Baskerville on the Age of Anxiety title page; is that the face you've used throughout the book? It strikes me that typefaces have the potential to cause an e-reader headache quite separate from that of lineation, because they're so capable of adding another layer of meaning to a text, alluding to one another and to their own histories, etc. All books about the Declaration of Independence are set in Caslon for a reason.

That's something most readers mostly overlook, but per Siobhan's post, is it completely dispensable as part of the literary work? If an e-reader sets all texts in the same font, is a valuable aesthetic resource being lost? Just another wrinkle in a very interesting discussion.

Brian, I tend to think of typefaces as associative cues for readers — subtle instructions in how to read a text. All of the "Auden Critical Editions" are using that Baskerville — which I think is lovely, by the way — because it lends a certain traditionalist dignity to the proceedings and creates uniformity among the editions. But clearly Auden wouldn't have liked it, because he wanted a typeface used largely for textbooks in order to block the usual "poetic" and "artistic" associations.

All that said, most typefaces, even for poetry, are not distinctive enough to generate really powerful cues. Occasionally our reading experiences are shaped by typefaces in ways that we're aware of, but most of the time, I think it's fair to say, the typeface is a neutral element. The Kindle and other e-readers are counting on neutrality. But in so doing they are removing one of the means by which we distinguish one reading experience from another. And as Siobhan says, all these matters (and other typographical elements) are intensified in the case of verse.

Incidentally, I have come to believe that my forthcoming book on reading simply must be set in eric Gill's Joanna. I just see it in that face, and am really going to press Oxford to use it. I have no idea what the response will be; it's going to be interesting.

A few years ago, as an experiment, I converted one of the more complicated pages of Susan Howe's "The Nonconformist's Memorial" into Flash, carefully putting the text at the same places and angles and with the same intersections and overlaps (as well as I could within the constraints of the program), and added buttons to allow rotating all of the text at once. When I showed it to people, I was very amused to discover they were much more likely to turn their head to read than to click the little buttons and turn the text.

Another culprit in the familiarly poor electronic presentations of poetry– big, comprehensive text databases, like Literature Online (LION). I happen to know that some of the XML their texts are based on have more detailed presentation information than they are using (or at least were using last I looked); when I was working with these texts a few years ago I discovered a whole group of poems with details in the encoding that indicated they were meant to be right-aligned, which made them much more interesting to read, at least to my eyes.

Related, but different question: how useful is it for poetry to be full-text searchable anyways?

How much do you suppose our current poetic forms owe to the size of pieces of paper or chunks of rock? Now I'm starting to try to imagine a poem where the fluidity of line breaks as the containing window/frame/e-reader changes size (or a device is rotated) could be meaningful, important…

When I showed it to people, I was very amused to discover they were much more likely to turn their head to read than to click the little buttons and turn the text.

Muscle memory!