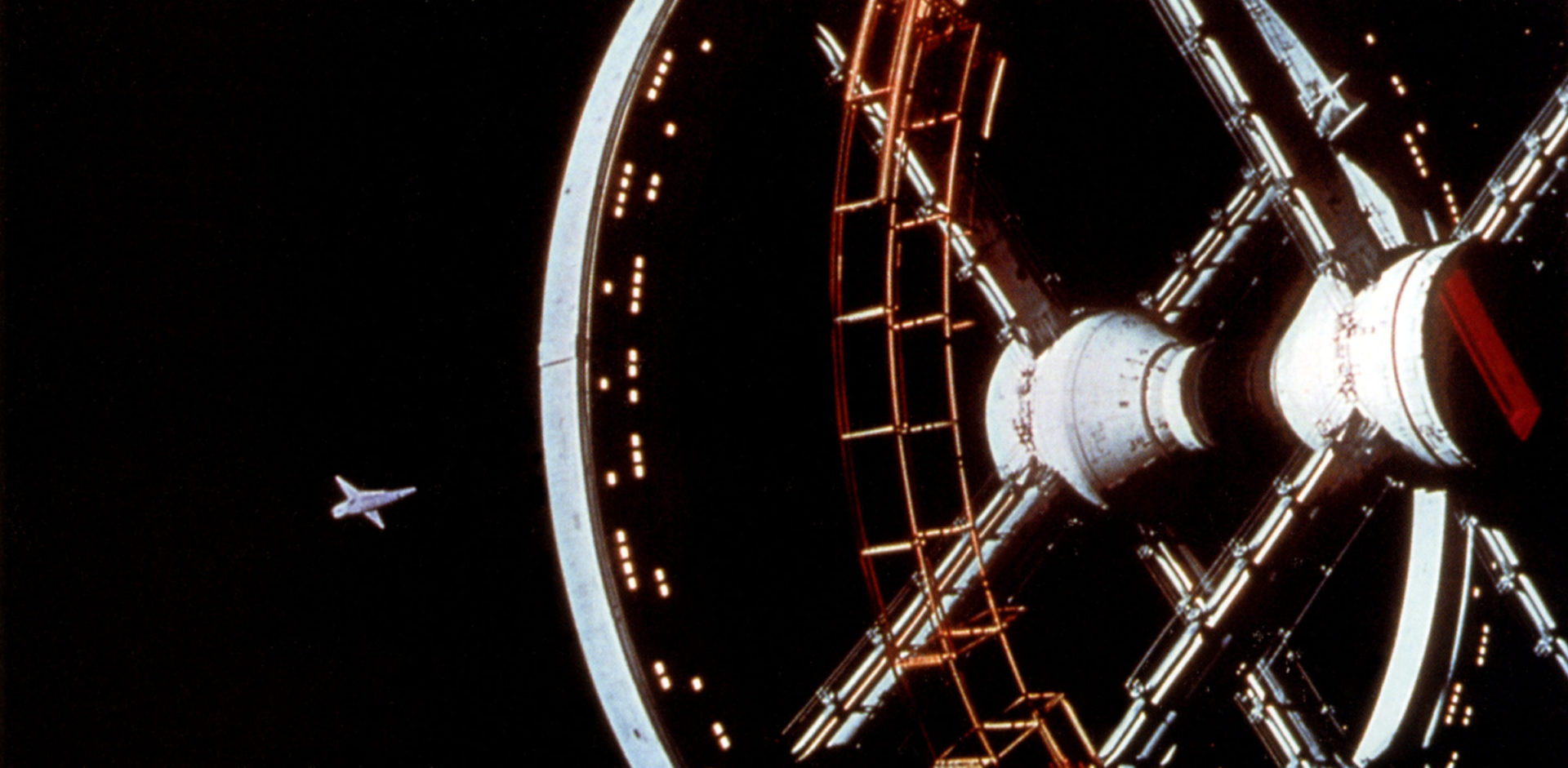

A needle-sleek space shuttle approaches ever closer to a huge, double-ringed space station. Earth hangs in the background, blue and green and beautiful. The station rotates slowly to provide at least its periphery with artificial gravity. But that means the shuttle also has to start rotating, in order to dock with it. It is an intricate dance, carried out with precision and a beauty of its own. On board the shuttle, there is but a single passenger; he must be a VIP on a mission of some urgency! As he proves to be. But just for the moment — the wonders of space and space travel and space colonization unfolding around him — he is napping. A stewardess maneuvers carefully in zero-g to his seat to retrieve his pen, which is floating nearby.

This is only the beginning of his journey, and yet for that napping bureaucrat all the marvels of technology he encounters, representing a “conquest of space” we can only wonder at, are just business as usual. Such was the world of 2001, as envisioned in Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey. A world that for any space nerd was marvelous to behold when the film came out in 1968 remains as marvelous to us today.

Kubrick brilliantly presented a tension still at the heart of current human spaceflight efforts, a tension between what is wonderful and what is routine, between the extraordinary and the prosaic. While the tension was evident from the early days of the United States space program, finding ways to deal with it will only become more important as sending people and material into space becomes no longer a government monopoly enabled by private enterprise, but a new hybrid of public and private efforts. Under such a hybrid model, there will be both commercial and political reasons to build public support for exploring and exploiting space. Consensus being notoriously difficult to maintain at the present moment, such support can hardly be taken for granted, as, indeed, it was perhaps lacking even in the Apollo era.

When space travel becomes routine, we can maintain excitement about it, and wonder at its results, by thinking about it as an opportunity to exhibit a kind of excellence analogous to, but rather broader than, that which maintains a wide public interest in sports. That sporting events are repetitive, highly organized, and bound by rules does not detract from — but rather, focuses our attention on and admiration for — the virtues needed to excel.

As the story is often told, even before the era of manned lunar exploration ended, policymakers and the public were losing interest. It was enough to have fulfilled the promise of President John F. Kennedy, and to have “beat the Russians.” President Richard Nixon may have paid lip service to bigger and bolder goals when he announced the space shuttle program, but he was also clear about the shuttle’s less-than-inspiring purpose — to “revolutionize transportation into near space, by routinizing it.” Perhaps we should better appreciate the wonders of the commercial world, but to make something routine is precisely to suck the wonder out of it, to make it uninteresting. And indeed, that is pretty much what happened.

It may seem odd that things should have turned out this way. For while many are the wonders of our technological powers, surely few are more wonderful than our ability to reach outer space, and to survive there for extended periods. And getting into space is just the beginning of the wonders. The sight of Earth from space is widely regarded as having a special psychological power, the “overview effect,” shaking complacent views about our place in the universe and our relationship to the planet. Pictures of bleak lunar vistas with visiting astronauts are so uncanny that some believe they cannot possibly be real. It seems only appropriate that human space exploration should invoke wonder, amazement, and curiosity, that it should be exciting or at least widely interesting.

But the history suggests otherwise. Consistent with the goal of routinizing spaceflight, at the end of the Apollo program NASA started to put less emphasis on human space exploration. We are now fifty years from the last manned Moon landing on December 11, 1972, and despite all of the technological developments that might by now have been used to build a permanent colony on the Moon, say, or even to put early human explorers on Mars, what we saw instead was the now-defunct space shuttle and the obscurely purposed International Space Station.

As far as NASA itself was concerned, for a long time it looked as if the routinization of space travel meant keeping the ISS supplied and staffed. Once the shuttle program ended, that meant little more than paying the Russian space program to ferry our astronauts. Reports outlining bigger plans for the Moon or Mars appeared periodically, yet only recently has NASA taken concrete steps toward a return to the Moon, with plans for a journey to Mars by 2040. But already the lunar program is bogged down in delays and cost overruns.

In short, the routinization of space travel to and from the ISS meant that nothing was going on in the government space program that was likely to excite or sustain much interest in human spaceflight among the general public, with policymakers pretty much following suit. In contrast, the extraordinary success of some unmanned missions (Hubble, the various Mars explorers, and now the Webb telescope) demonstrate that NASA can still generate innovative and sophisticated projects that capture public attention. That capacity was simply not directed to human spaceflight.

But then, bursting out of nowhere — or so it might have seemed from the news coverage, anyway — came the “billionaire space race” and with it the promise of space tourism. Richard Branson (of Virgin Galactic), Jeff Bezos (Blue Origin), and Elon Musk (SpaceX) were bankrolling upstart aerospace companies that were going to send private individuals into space for the price of a ticket, albeit a very expensive ticket — Virgin charges $450,000. (Had he not passed away in 2018, Microsoft co-founder Paul Allen would likely have been included on this list.)

The billionaires were competing using innovative launch vehicles that their companies had engineered on their own. Closely timed maiden voyages of the Virgin and Blue Origin vehicles in late 2021 meant that, suddenly, human spaceflight was so salient that news outlets published articles discussing just how high up tourists would have to go to “really” have been in space. In the meantime, SpaceX rockets had been ferrying supplies to the ISS since 2012, and astronauts since 2020. In 2022, Axiom Space sent paying customers to the ISS for the first time at $55 million per passenger. These wealthy investors rejected the label of “space tourists,” and they did conduct some research while they were there. And so another rationale was added to the muddled story of the ISS: now it could serve as a sciencey space hotel. The paying customers, who had a delayed return to Earth due to unfavorable weather conditions, were apparently surprised and not entirely happy about how busy they had been kept on the ISS.

The spectacle of a few extremely wealthy individuals charging a slightly greater number of very wealthy individuals for rides into space excited wide comment reflecting on everything from making space travel like Walmart (understood as a good thing), to the vanity of rich people, to capitalism’s failure to meet real human needs, to the prospects for interplanetary imperialism and technological utopianism. But the framing for this commentary was often somewhat misleading on the question of how and why tourists were going into space at all. All three space entrepreneurs had much more in mind for their enterprises than tourism. Each was seeking government contracts for manned and unmanned launches (SpaceX with the greatest success so far), and in turn the government’s long-term goal of commercializing and routinizing space travel had created a favorable government regulatory environment for their efforts.

If “man in space” had become rather boring, tourism, whether you are for it or against it, seems just the thing to reignite interest at the same time as it opens the door to commercialization and further routinization. Making a profit from transporting tourists is, after all, a well-established commercial paradigm (Branson made a fortune that way already). And although at least for the near term this particular kind of tourism will fall into the niche category of “somewhat dangerous and uncomfortable things rich people can do on vacation,” space tourists are unlikely to want to replicate all the risks of space pioneers, and to that extent will want each trip to be more or less routine for all but the passengers. William Shatner was comped a ticket on the first Blue Origin tourist flight, and his tearful reaction on returning to Earth illustrates just what all these companies must be hoping for:

Everybody in the world needs to do this. Everybody in the world needs to see it…. to see the blue color whip by you, and now you’re staring into blackness….

I’m so filled with emotion about what just happened…. It’s so much larger than me and life. It hasn’t got anything to do with the little green planet and the blue orb. It has to do with the enormity and the quickness and the suddenness of life and death.

Although there is precedent for providing charitable tickets to those who could not afford them on their own, for some time to come most of us will only be able to experience the wonder and excitement of these trips vicariously. But that’s not so bad. Travelogues and video travel diaries (often written or supported by more rich people) remain a popular genre in our media-hungry world. The ever-changing vistas of the Earth from space will be a marvelous visual storehouse, and the voiceovers will doubtless reflect a wide variety of individual perspectives, particularly to the extent that they will not share the laconic tendencies that seem so common in the nature and nurture of professional astronauts. Short trips will beget the short stories that conform to current attention spans. Even better, one will be able to “see the slides” of someone else’s trip into space on Facebook or Instagram, without, as was once the case, being a captive audience in their home.

In the longer term, Virgin Galactic envisions a far more widespread access to space. While Richard Branson has been the least voluble of the three billionaires, the corporate Virgin vision of the future is easily available online, presented in careful corporate-speak. The justification Branson offers for space tourism is that it will “open space to everybody — and change the world for good.” This is how the company explains its mission to prospective employees:

Virgin Galactic recognizes that the answers to many of the challenges we face in sustaining life on our beautiful but fragile planet lie in making better use of space.

Sending people to space has not only expanded our understanding of science, but taught us amazing things about human ingenuity, physiology and psychology.

From space, we are able to look with a new perspective both outward and back. From space, the borders that are fought over on Earth are arbitrary lines. From space it is clear that there is much more that unites than divides us.

Or consider this marketing material from an earlier version of the company’s website:

INSPIRATION

There is little that compares to the sense of awe that takes hold as we raise our eyes to the night sky.

Despite the fact that millions of people would love to experience space, fewer than 600 have been given that opportunity. And despite there being a common understanding of the benefits of space-based research, there are still few scientists who have the chance to reap its benefits.

It was this that inspired the creation of Virgin Galactic.

To its credit, Virgin addresses doubts that have been around since the earliest days of the space program: Why are we expending resources on space when we have so many urgent problems here at home? Whereas in the earliest days of space exploration the Virgin-like answers provided were necessarily speculative, today there is a track record, and it is not a bad one. Space as a platform from which to study Earth has proven itself again and again in practical ways (such as weather forecasting with satellites), and if its power to create a cosmopolitan vision of a fragile, borderless planet (the overview effect) is not universally evident, it is evident enough for such ideas to appear, as they do in Virgin’s mission statement, somewhat clichéd.

Virgin’s broad goals, the company says, will be achieved by the creation of

a basic space access infrastructure that will act as an enabler for scientists and entrepreneurs. It will also provide the catalyst for a new age of space exploration which promises enormous positive potential for life on Earth…. The resulting economies of scale and competing technologies will lead to further downward pressure on the cost of launch — enabling an ever-increasing number of users with diverse, world-changing applications.

In short, Virgin seeks to do for space travel (and for satellite launch services) what it did for airplane travel, and then some. While the original Virgin brand made use of an existing air travel infrastructure rather than developing its own innovative aircraft, its rethinking of air travel helped to lower the cost of an airplane ticket and encouraged people who would otherwise not have been able to do so to travel simply for the pleasure of traveling. It also extended the reach of business travel for those without the resources of large corporations. If we do not immediately see the results of Virgin’s original innovations in terms of “awe,” “exploration,” or a certain cosmopolitan outlook, that may have something to do with our taking for granted the rather amazing things that relatively low-cost air travel makes possible, and our general lack of wonder at the achievements of the commercial world. Many Kickstarter entrepreneurs wind up jetting off to China; and awe-inspiring vistas, once only reachable by arduous journeys, are available to anyone who can afford a package tour and a few days of vacation time.

But the fact that we can and do take routinized air travel for granted is significant. There is a good deal of interest to be seen from an airplane; the vistas would have once been considered amazing. Yet airlines do not set up external cameras and provide a narration for the sights below. On the one hand, what would serve as a better symbol of having reached the point of routinized use of space than regularly scheduled tourist flights, and the “spaceports” (some already built) to go along with them? What might energize the wonder at the cosmos, at the beauty of our “fragile planet,” more than increasing numbers of people having direct experience of it? On the other hand, what would kill that wonder more quickly than sudden launch delays or re-entry cancelations, futuristic facilities that quickly show their age, delicate space toilets, space-sick fellow passengers, and the inevitable deaths and accidents?

Space tourism may shift the needle back toward wonder for a time, at least, but the more it succeeds in its goal of making space ever more easily accessible to ever more people, the more that needle will start to move in the direction of routinization. The billionaires competing in space seem to understand that something more will be necessary to sustain interest, and two of them have chosen proven motivators: seemingly science-fiction visions of progress that could turn into real futures. This progressive outlook is so familiar that it requires some unpacking before we see how it applies to the billionaire space race.

Progress implies some kind of goal: How could we make progress on a journey that has no destination? The sense of purpose or even destiny that progress supplies prevents us from being complacent about our present achievements; there is so much more to do! But it also allows us to have a certain pride. Whether or not we live to see it, we have made our contribution to some big goal. This mindset is very much of a piece with that of modern natural science and technology, at least in idealized form. Each researcher and inventor makes his or her contribution, on whose basis the next generation of research and development can further advance. So whatever the subjective mental state of a given bored bureaucrat traveling to the Moon, a vision of progress can turn his trip into a meaningful moment in the human story, and thus imbue it with interest and even wonder that such grand ends are being achieved through such mundane means. We see something of such a vision of progress in the Virgin rationale. Here’s more from it:

EXPLORATION

Throughout history, the urge to see what lies just over the horizon has led us to find new places to settle, helped us identify new resources, and taught us new skills to overcome complex challenges.

As a global community, we will grow and evolve only through continuing to explore the unknown.

The exploration of space is the ultimate expression of the human desire to push boundaries and stands at the pinnacle of our species’ achievements. Not just for the ingenuity required, but for the fact that without it, modern life would be unrecognizable.

But this is a rather formal account of building effort upon effort, with ultimate goals and purposes somewhat underdeveloped. Musk and Bezos, in contrast, have much more clearly specified pictures of progress.

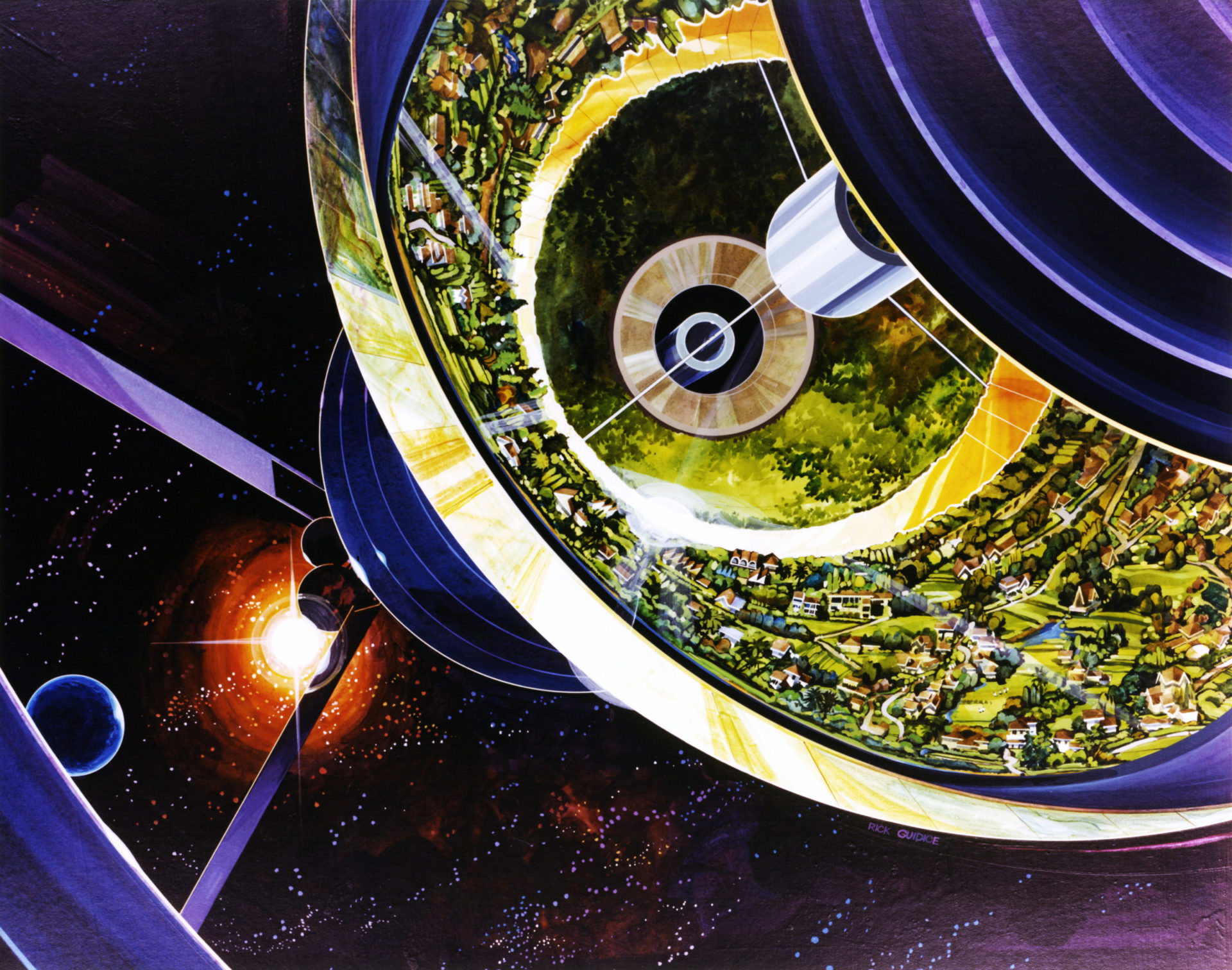

Jeff Bezos’s vision of the human future in space, which some have called “epic,” is not entirely original. He presents what is in effect an updated and somewhat sanitized version of a future first described by J. D. Bernal in his 1929 classic The World, The Flesh and the Devil: An Enquiry into the Future of the Three Enemies of the Rational Soul and then updated for the space age by Gerard K. O’Neill in his 1976 book The High Frontier: Human Colonies in Space. Bezos looks forward to a time when space will be the primary habitat for humanity, with the Earth “zoned residential and light industry” (“light industry” meaning Amazon warehouses?) to preserve it as “the gem of the solar system.” Otherwise, Malthusian limits to the growth of terrestrial energy production will have a worsening impact on our ecosystems. So most of humanity needs to be off the Earth to save it from the destructive consequences that would otherwise follow. But having rezoned the Earth and made space humanity’s primary habitat, the problem of limits is greatly reduced. Bezos thinks space colonies could support a population of one trillion in comfort (air-conditioned space stations would have weather like “Maui on its best days”), and furthermore with such a large population that humanity could have the benefits of “1,000 Mozarts and 1,000 Einsteins.”

Bezos provides a resolution of sorts to a debate that helped define twentieth-century environmentalism. Many of those who believed in limits to growth advocated for deliberate, radical population reduction, which was for the most part a non-starter. Those who advocated for technical solutions to environmental problems often advocated for doing more with less, which implied another less-than-popular form of restraint. Fairly or unfairly, believers in the good consequences of economic growth for people and the environment usually found themselves called anti-environmentalists. Bezos allows us to have our cake and eat it too. Amazing growth remains possible without sacrificing Earth’s environment if we direct that growth to space colonies.

Despite the lovely green-dominated graphics that accompany many accounts of Bezos’s vision, right now we know only the most generic requirements for engineering and building these habitats, and even less when it comes to keeping them going materially or socially. Why people would want to live in them, aside from enjoying the climate of Maui and the prospect of flying more or less like a bird, is likewise an underdeveloped area of Bezos’s vision — unless he imagines that a properly zoned Earth, like many properly zoned neighborhoods today, would be too expensive for most people to live in. If we imagine, as many do, that today’s global population of roughly eight billion already strains global ecosystems, then a reduction to, say, one billion living on the planet itself would mean that in Bezos’s world of one trillion people total, Earth would be for the one tenth of the one percent — that is to say, for the 1,000 Jeff Bezoses and the 1,000 Elon Musks.

Why Bezos’s vision deserves to be called “epic” rather than “bourgeois” is ultimately unclear. Bernal at least imagined his space habitations as just a few steps away from becoming multi-generational starships that would expand from our solar system to inhabit other parts of the galaxy. But Bezos takes one of the advantages of his colonies to be their proximity to the rezoned Earth, unlike what would be the case for any effort to colonize hostile planetary surfaces in our solar system or among distant stars. This vision is ambitious, surely, in the doing of it, but the goal is comfort and ease rather than risk and exploration. Maybe that is a good thing?

In contrast, the way Elon Musk sometimes tells his big story of progress is heroic to a fault, as when he freely acknowledges that astronaut deaths will occur in the course of the effort. Musk’s idea of progress is pretty simple, relying on well-established and better-known man-in-space tropes: He believes that failing to become a spacefaring race that can colonize other planets is a route to human extinction. Along with the effort will come a “tremendous sense of adventure.” Or as he has also put it,

A lot of people are sad about the future and they’re pessimistic. And I think this is not great. I mean, we really want to wake up in the morning and look forward to the future. We want to be excited about what’s going to happen. And life cannot simply be about solving one miserable problem after another.

If I were to bet, I would bet on a Musk expedition landing on Mars before the first Bezosville is built in space. But Musk’s vision, like that of Bezos, is built on a huge faith in “progress” in the sense of a belief that any and all technical obstacles and knowledge deficits can be overcome. For the time being, their arguments require a good to deal of hand-waving to avoid known unknowns, let alone trying to anticipate presently unknown unknowns. And, as open-ended as it is, something very much like the Virgin vision has to be the basis for the future they are looking to.

By articulating big goals, Musk and Bezos are attempting to find a way to imbue their commercial operations, which will necessarily involve routinization if they are to be successful, with a larger significance that will maintain interest and excitement. The competition between world-famous billionaires with different visions of the future might help broaden public interest in space exploration, even if for many the specifics of their visions of the future might not be particularly compelling. Only time will tell how much these visions actually engage the public mind, or how important that engagement will prove to be. But it is possible at least that competitive space programs may help to address the problem that successful achievement is always something of a threat to the effort required to take the next steps beyond it. If that were not the case, we would hardly need to be urged not to “rest on our laurels.”

Yet whatever the merits of their specific progressive visions, Musk and Bezos also remind us that ongoing space exploration, exploitation, and settlement in and of themselves will present us with a whole slew of challenges on a scale that is unprecedented in the annals of human exploration, exploitation, and settlement of Earth. The ongoing parade of novel experiences this situation will produce could be a constant source of innovation and wonder, even if commercial competition (like national competition) turns out to be not always engaging or edifying.

Thinking about competition reminds us that sports, whether professional or amateur, are strictly routinized in the sense that they are bound by the rules of the game and by the skill of the players. (Watching very young children without any skills play sports is an exception; it is amusing because their play is not yet routinized.) When you go to a baseball game, you know already the broad outlines of how the game is going to go. And yet the game is still capable of exciting interest. Often this interest has a good deal to do with a personal stake of some sort in who wins and who loses (bragging rights, fandom, money), but that is not the whole story. A game may be dull or uninteresting or bad even if one’s preferred team wins — the players did not hustle, the play was marred by thoughtless mistakes. Seeing the excellence of the players’ performance is a crucial part of the interest we have in watching the game.

Much the same is true with musical performances. There can be the same routinization of rules and skills. An audience member may have heard at least some of what is on offer at a concert many times — may even have decided to attend because the pieces are well known. And in this case there are no winners and losers. There is an interest in the music itself, but that is closely linked to the prowess with which it is played.

Following this lead, we can chart a path toward getting inspiration out of routinization in the case of human spaceflight. If we aspire to do excellently what is routine — and just as in aviation there is every self-interested reason to aim high in space travel — then the routine becomes like the practice of an athlete or musician. Do something again and again and again in the right frame of mind, and you can not only become really good at it, you can become very self-conscious and intentional about the practice. Your excellent practice will also allow you to aspire to, and to see, ways in which you can become even better, can push the boundaries, can perhaps even risk more as you explore new possibilities (think of the developments in women’s figure skating and gymnastics over the past decades). Now we have a situation where routine, pursued with the goal of excellence, produces interest, innovation, and exploration — just what a spacefaring civilization will need. And all this is only encouraged by the hostility of the space environment itself. If we are to colonize the Moon or Mars, let alone go beyond them, we will need to accept the risks these efforts will pose for those who undertake them, yet will want to be sure that the very best, most dedicated people are doing the jobs that will need to be done. (For many of them, the risk will likely be a motive, not a disincentive.)

So routinization can actually create the conditions for and attitude toward human space exploration that will have inspirational consequences. This is an outlook that will help justify the continued human presence in space in the face of ever more capable robots. A willingness to tolerate risk, the desire to seek the increase of knowledge, and the attempt at innovation will allow us to explore in person many a “strange new world” without even leaving the solar system. It may be a spiritual weakness that we more readily feel wonder with regard to the unusual and the novel than with regard to what we are accustomed to, but there it is.

So far we have been talking about the people engaged in the work. What about the rest of us? The examples of sports and music show that people not capable of a given excellent practice can also admire and be inspired by it — sometimes even when the practitioner is uninteresting or unpleasant as a person. Thus, contrary to Branson and Bezos, the inspiration required for developing space travel does not require that actual access to space be “democratized,” or that it be a goal that space travel become as everyday as an elementary school field trip. Once upon a time, both young and old were inspired by the words of explorers, written or spoken. Then came pictures and films, then IMAX, and soon VR. We can leave aside the strengths and weaknesses of these different modes and simply note the power of each to inspire in its time, and perhaps beyond its time — the Folio Society does not offer a fine-quality three-volume edition of the journals of James Cook for $195 because it thinks no one will be interested in it. I enjoy pictures from deep space as much as the next guy, even knowing how often the colors are false and the topographies exaggerated, but it is the stories of dedication, hardship, and ingenuity, “the thrill of victory and the agony of defeat,” that will recruit people with “the right stuff” to go into space, and create a society that will support their efforts.

No Walter Cronkite of the future is going to rivet the nation with coverage of the latest departure from Spaceport USA. The routinization that undergirds the billionaire space race has to have the right kind of goals if it is not to remain only at the service of the very wealthy, whether governments or individuals, and ultimately end up (absent military usefulness) mere showboating. Those purposes may have their place, but they will not lead us to being spacefarers, because they will not provide the broad inspiration that the billionaire competitors aim to produce. My own judgment is that the grandest purposes of Musk and Bezos are not as stirring as they seem to think; while there is some advantage of Musk’s side, both visions are too distant, too much utopias of the rich and nerdy. We need something much more like what glued Americans to their TV sets in the 1960s: a sense that we were watching competitively selected, highly trained individuals putting their lives at risk for the increase of knowledge and the service of their country, with a great dedicated and inventive workforce standing behind them at the cutting edge of human technical abilities. The tiny Mission Control in Houston seemed so large on TV not only because of the cameras used to broadcast it.

In sum, there is a conception of virtue that is appropriate to bring to bear even at the technological frontier. It cannot be the kind of virtue that once sustained centuries-long efforts to build cathedrals, as useful as that would be for space travel if it were available. But neither is it a kind of virtue confined to the useful or profitable, or a virtue built entirely for the conquest of nature, the virtue of the “deicide” — the god-killer — that J. B. S. Haldane ascribes to the scientist and to Daedalus in his essay by that name. We are talking about virtues like intelligence, curiosity, creativity, pluck, dedication, resourcefulness, sacrifice, inventiveness, courage, high-spiritedness, humility, focus, diligence, industry, toughness, and risk tolerance. I have drawn many of these traits from a recent reading of the first chapters of Ernest Shackleton’s The Heart of the Antarctic. Shackleton presents some of them directly in terms of what he was looking for in assembling his team. Others are exhibited from early on in his story, even during the often difficult trip south. They are the virtues of explorers.

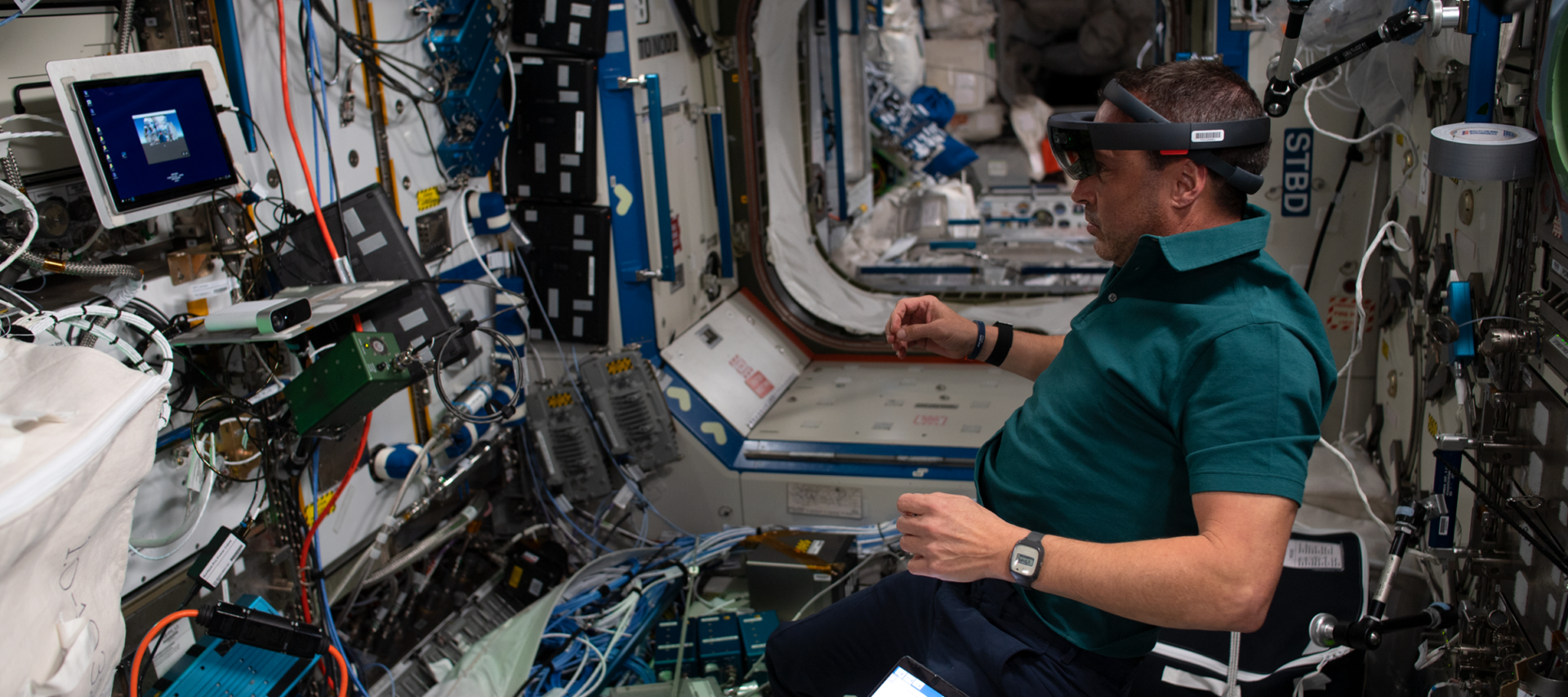

Is it anachronistic to cite them in the context of human spaceflight? There was no government or business bureaucracy behind Shackleton, no instant communication with a support team, not much complex and intricate equipment to maintain. Perhaps most to the point: NASA has always worked very hard to try to minimize the risks astronauts run, with repeated simulations for training and checklists and schedules dominating actual operations. (Musk has indicated a different view of risk.) From this point of view, it is almost as if the astronaut is the last in the chain of command when a switch needs to be flipped. Who better than the astronauts can understand the complexity and risk that calls for space operations to be highly structured and run as a team effort?

But here too it is easy to discern a tension that brings certain virtues back into the picture. Astronauts, who are appropriately drawn from the ranks of the more risk-tolerant, have wanted from the beginning to be more than “spam in a can,” and so they periodically revolt against the tyranny of Mission Control’s schedules. These very accomplished individuals want to be able to exhibit that they have “the right stuff,” and this instinct is sound. As space operations become even more complex and more distant, to err on the side of routinization and try to confine astronaut roles to flipping the right switch at the right time under the ever-watchful eye of government or corporate mission controllers would quickly undercut a human presence in space altogether. As robotic probes become more and more capable and reliably autonomous, that last hand on a switch does not have to be a hand at all.

When it comes to the role of virtues in space exploration, there is also a question of how a human space program is presented to the public. Traditionally, it seems as if NASA has followed not only a strategy of risk minimization with respect to missions, but also in communicating to the public about those missions. Of course, it is to be hoped that all mission parameters are “nominal”! But it becomes easy to forget that whatever is nominal takes place within the framework of a crazy-dangerous enterprise. In the TV series For All Mankind, astronaut Edwin Baldwin replies to his crewmate Molly Cobb’s wonder at having been cheered on the way to the launch pad by saying, “You did just strap your ass on top of a quarter-million tons of high explosive for government pay. It’s not smart, but it’s something.”

Thanks to Tom Wolfe, Hollywood has sufficiently recognized the dramatic, indeed heroic potential for stories of real-world astronaut virtues that go beyond technical prowess to make The Right Stuff, and even found the drama in the Mission Control team in Apollo 13, so these stories of intelligence, inventiveness, and courage are relatively well known. But there are other such stories that might be less well known because of NASA’s strategy of risk communication and the typical astronaut tendency to understatement. Neil Armstrong’s training, focus, and toughness allowed him to make a lifesaving decision on Gemini 8 when a malfunctioning thruster put the capsule into a potentially fatal spin. Gene Cernan faced poorly designed equipment and lack of practical knowledge about how to maneuver in zero-g during his Gemini 9 spacewalk, but he persevered in the face of complete exhaustion, losing most of his forward visibility, and pain so extreme it was difficult to re-enter the cockpit. Upon splashdown it was found that he had lost nearly thirteen pounds of water. In a different vein, there is Cernan and Harrison Schmitt’s high-spirited rendition of “I Was Strolling on the Moon One Day” as Schmitt skipped along the lunar surface during Apollo 17.

Whatever goals are set for the future of human spaceflight, whatever is actually achieved, these explorer virtues will continue to play a role as they have in the past; they will be there waiting to be noticed. There will always be aficionados of data attached to space exploration, and of cutting-edge technology, and of the advancement of science and of big things that go boom. But if public or private space efforts are to survive the winds of politics and the whims of the wealthy, it will happen to the extent that we ordinary people are engaged — as we always have been — by tales of extraordinary, heroic human achievement.

And the virtues we admire in our astronauts and the teams behind them will not be those of warrior aristocrats, for example, or of the saintly, but good, modern, republican virtues. They are practical of necessity, but part of their usefulness is the acquisition of useless knowledge. They are supportive of a kind of task-based natural aristocracy, but they will often be more a result of dedicated effort than natural talent. They place individual excellence within a framework of teamwork. They will serve progress because they will push the boundaries of the possible, but they will also be conservative for being human virtues building a human future. Some of our billionaires seem to have conflicted ideas about the possibility or desirability of a human future; it would be a good thing if their efforts to get into space would help keep their feet on the ground.

Exhausted by science and tech debates that go nowhere?