There is a profound paradox in great cities today. We are accustomed to thinking of our cities as engines of creation, where creatives and disrupters of all stripes go to prosper. Yet at the same time we see widespread fears that in the future the very urban structures that have come to be the incubators of change will be particularly vulnerable to the destructive powers they have unleashed.

Futurist-oriented thinkers have easily envisioned city- and civilization-destroying conflicts since at least World War I. With the advent of nuclear weapons, such futures became even easier to imagine. Add to that decades of the looming specter of environmental destruction, with its direct or indirect consequences for the viability of cities, and dystopian urban futures only become more plausible. Covid seems to have called into question just how necessary great cities are in a world of broadband communication.

Widely acknowledged as the originator of the cyberpunk subgenre of science fiction and inventor of the term “cyberspace,” the novelist William Gibson writes of future cities as working out the consequences of this paradox. Many of Gibson’s science fiction novels start with serious destruction through war, natural disasters, climate change, or global ecological collapse. And his cities of the future are the stage where he plays out stories about virtual realities, brain–machine interfaces, artificial intelligence, genetic engineering, and nanotechnology — the very constellation of technologies that some anticipate will allow, and in Gibson’s work have allowed, humans to interact in all kinds of new, non-physical ways that will both obviate the need for physical cities and create posthuman forms of intelligence far exceeding our own, calling into question the primacy of our creative efforts.

What makes Gibson’s portrait of great cities thought-provoking is that, despite all this change, he imagines them persisting at all, in some ways operating no worse than the worst that can be found today. This situation becomes all the more thought-provoking when we see how he links the fate of his cities to the fate of the modern project itself, whose deep impact on making cities what they are today will persist into the future.

The modern project — meaning here not just scientific and technological progress, but also liberal democratic politics, free market economics, and social egalitarianism — promised to alleviate many of the historical givens of the human condition, like material scarcity, rampant disease, inequality, and social and political oppression. And it absolutely has expanded the possibilities of human life for vast numbers of people over the course of time. Yet for Gibson, the modern project is also in some ways responsible for, or at least unable to prevent, the civilizational crashes his stories anticipate. Modernity does not survive unaltered in his stories. The technological center no longer holds, and we see increased social stratification and the rise of oligarchic political and economic arrangements of a sort that some will say are quite familiar today.

In fact, it is Gibson’s critique of what he calls the “modern program” that accounts for his belief that cities will persist under circumstances seemingly so unfavorable to their existence. By his account, a failing of the modern program is that it puts too much emphasis on the material conditions of urban life, and pays insufficient attention to its ethical dimension — how a city supports or undermines what people think of as a good life. The great modern city, Gibson understands, has no unified vision of the good, but becomes what it is by being an arena in which many such visions can interact. This situation creates dangers, most obviously the potential for conflict. But it also creates opportunities for accommodating diversity, adaptation, a certain kind of freedom, and even the adoption of ways of life that stand in a countercultural relationship to modernity. Each of these in turn presents its own set of dangers and opportunities. This complex way of life, Gibson seems to be saying, is what the modern city is, and what cities of the future could remain.

Like all science fiction authors, Gibson is an imperfect prognosticator. What we call cyberspace today has little resemblance to what he envisioned. After some forty years of anticipation, hackers still do not “jack into” cyberspace through a direct brain–machine interface. And we remain only on the verge of the various grand apocalypses that frame his stories. But we should not judge a science fiction author merely by how many of his or her inventions have come true.

What is of greatest interest in William Gibson’s portrait of cities is that for decades he has reflected and anticipated some of our biggest social, political, and economic concerns about their future, and has placed them within a plausible critique of the modern project that has been so central to their formation.

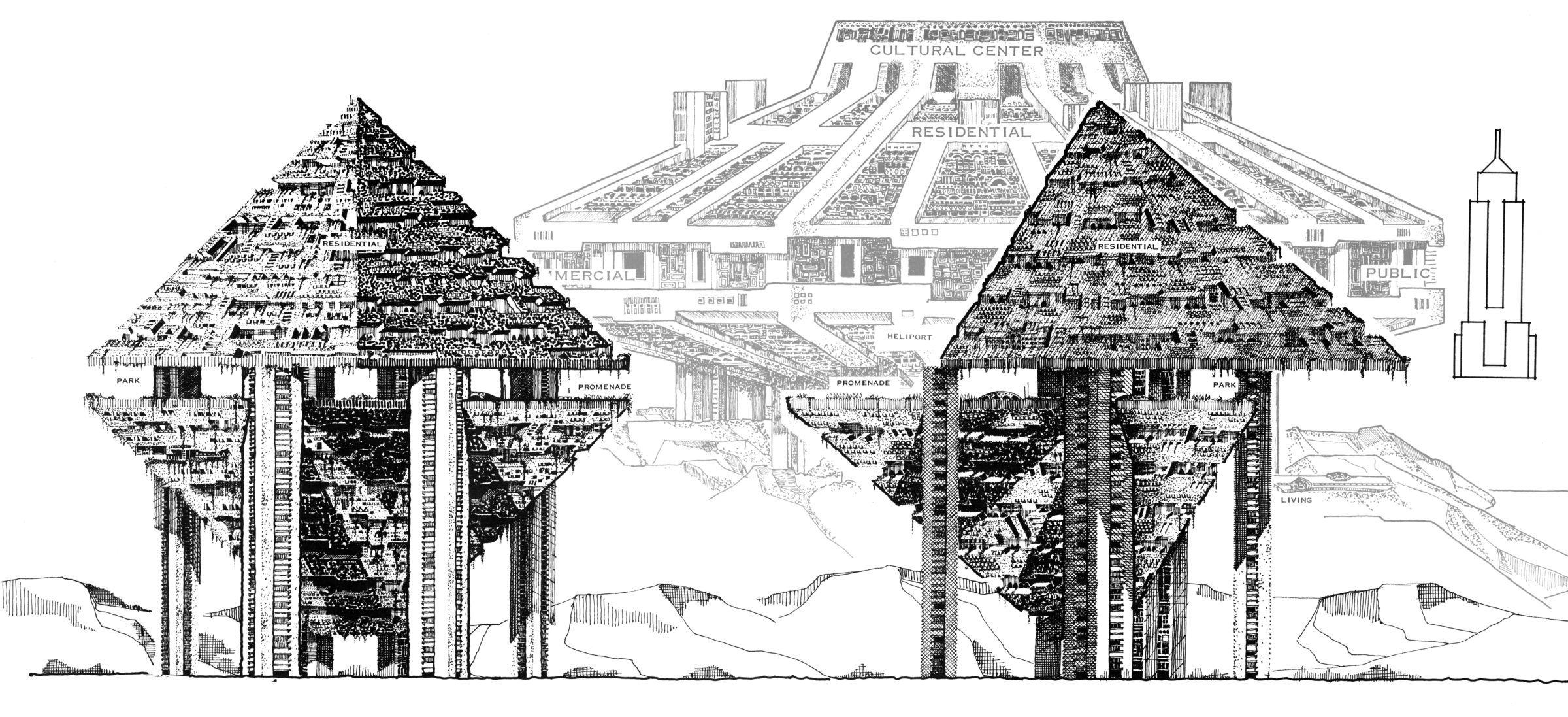

Many of the features in Gibson’s picture of the urban future have been envisioned by others before he wrote his novels. His 1980s Sprawl trilogy — Neuromancer, Count Zero, and Mona Lisa Overdrive — makes the most use of such features: the city-scale geodesic domes that Buckminster Fuller imagined around 1960, the “arcologies” of Paolo Soleri in 1969 (about which more below), and the lush space colonies of Gerald K. O’Neill in the 1970s.

When Gibson’s cities are not based on such modernist architectural futurism, they draw on historical realities. Much of the Sprawl trilogy takes place in the American East Coast “megalopolis,” first named as such and analyzed in a 1961 book by Jean Gottmann. The squatter settlement on the earthquake-damaged Oakland Bay Bridge that figures prominently in the 1990s Bridge trilogy — Virtual Light, Idoru, and All Tomorrow’s Parties — as well as the virtual-hacker refuge called The Walled City in the same trilogy, are loosely based on the real-life Kowloon Walled City. This was a densely populated enclave on the site of an old fort near the Hong Kong airport that existed semi-autonomously from after World War II to the early 1990s due to a jurisdictional dispute between Great Britain and China. Finally, Gibson’s rural America in the more recent Jackpot books — The Peripheral and Agency — while certainly impacted by futuristic technological developments, is completely recognizable as the portrait of small-town America popularized in the last decade: dominated by God, guns, drugs, large corporations, and a general lack of opportunity and amenity.

I do not offer these observations in a spirit of criticism. To the contrary, the way Gibson employs real and utopian urban visions of the past and present is part of what makes his work so interesting. As far as domes, space stations, and arcologies are concerned, Gibson makes them look much more realistic than the big projects their modernist creators envisioned. They believed, sometimes implicitly, sometimes explicitly, that physical structure is destiny. But Gibson wants us to notice that, were these projects to come into being, designed as they are to solve problems with previous urban configurations, they would do so almost certainly under less-than-ideal conditions that would alter their use and the experience of living in them as much as or more than the progressive dynamics their inventors anticipated. In other word, these urban projects would be subject to the same forces of change and decay as everything we build.

For example, the Sprawl — which in Gibson extends from Boston to Atlanta — contains multiple geodesic domes like the one proposed by Buckminster Fuller to cover midtown Manhattan. But in contrast to the iconic drawing of Fuller’s proposal, which shows a shimmering surface without any visible sign of its underlying geodesic framework, the domes in the Sprawl are in disrepair, some not even finished. When it snows, the snow sticks on the geodesics, highlighting the grayness of the unwashed glass. The Fuller dome was supposed to help deal with air pollution and climate control. Yet in Gibson’s story “a cold, grit-laden wind” scours the inner surface of one dome. There also seems to be a problem with ventilation: condensate from the dome creates precipitation, and the Sprawl smells bad — “Like Cleveland, but even worse,” in the words of one character. And we are told that “corporate obelisks … pierced the sooty lacework of overlapping domes,” which suggests that a desire for corporate display may have compromised the integrity of the geodesic structure.

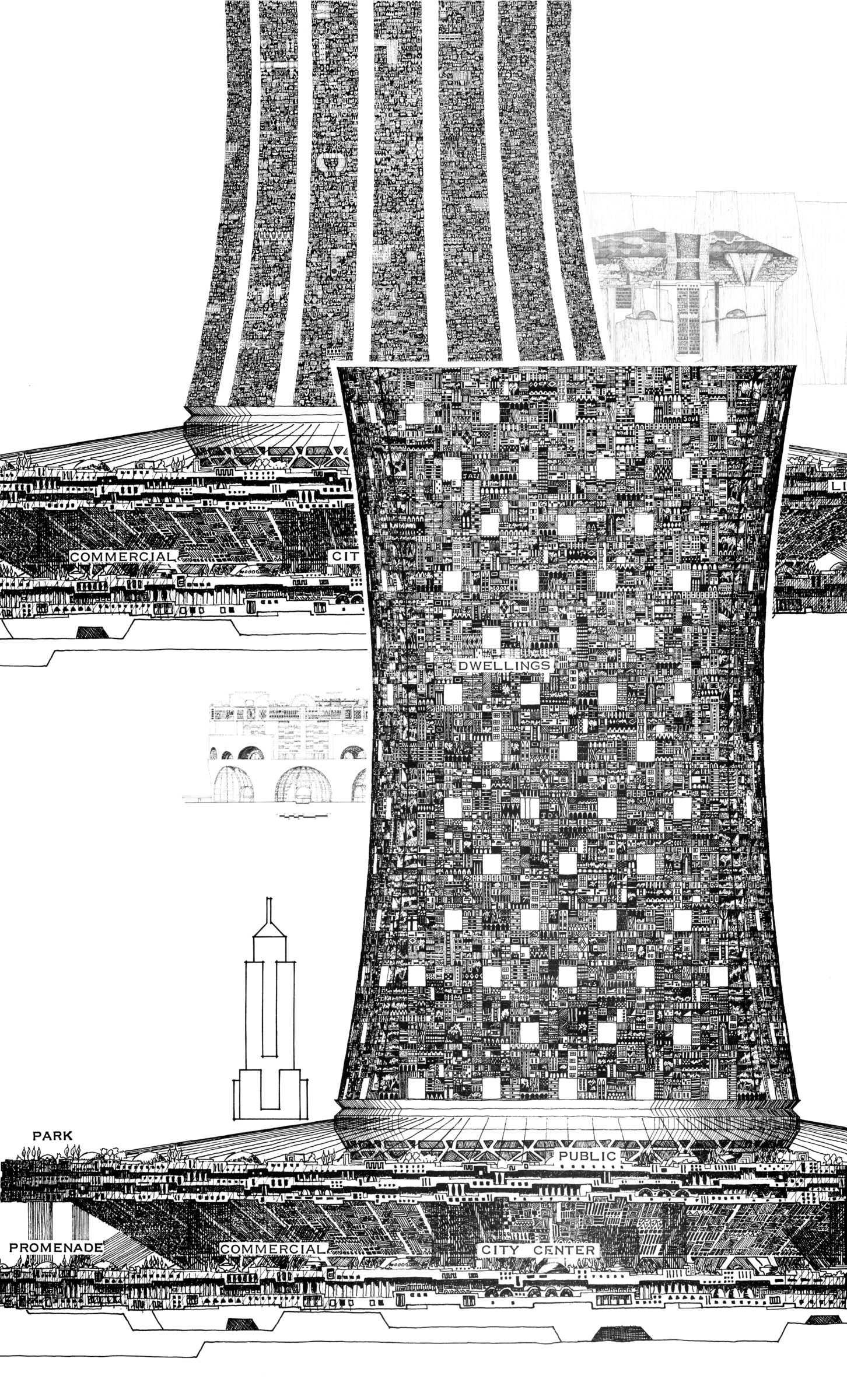

Gibson does not treat arcologies as critically as he does Fuller domes, at least not their physical structure, but he leaves deliberately ambiguous how well they would work socially and politically. That the word “arcology” comes from combining “architecture” and “ecology” pretty much defines the idea, as described in Paolo Soleri’s Arcology: The City in the Image of Man. Existing cities are environmentally unsustainable, Soleri believed. The wellbeing of nature and of humanity requires a vast densification of human settlement into a new kind of city, with all necessary functions integrated into a many-storied structure that far exceeds the scale of current buildings. Saudi Arabia’s The Line project — a proposed 110-mile-long city from the Red Sea into the desert, now under construction — is effectively based on one of Soleri’s visions of how an arcology might work, called the Lean Linear City.

The megastructures Soleri imagined are not strictly speaking self-sufficient, but they tend in that direction from the point of view of how any given resident is likely to experience life in them. The idea recalls a much older tradition of thought about cities, for self-sufficiency (of a sort) is one of the elements that for Aristotle distinguishes a polis from other forms of human association. The closest existing thing to an arcology, Soleri says, would be a cruise ship; he also links the idea with orbital space colonies such as those O’Neill explores. In short, Soleri saw arcologies as the far-superior alternative to the megalopolis represented by the Sprawl, with its bad consequences for natural ecosystems and for human community.

In Gibson’s Sprawl world, the arcologies exist in Japan as part of a corporatist social framework, and in America as the isolated desert base, built into a mesa, for a powerful company doing highly secretive biotech research. As private, commercially successful entities, there is no hint that they are subject to the kind of infrastructure maintenance issues that Gibson highlights with the domes. But in contrast to Soleri, who stressed the democratizing potential of his structures, Gibson sees them as working well within a framework of corporate paternalism and the discipline it demands. Their apparent self-sufficiency fits with a corporate culture that seeks to be secure and all-embracing. A major plot line of Count Zero is a military-like operation required to extract someone from the desert biotech arcology, and the violent response to those efforts.

One arcology that we see in greater detail, a huge building not far outside the Sprawl, tells a very different story. Providing housing for people who also receive minimum-income support, “the Projects” loom over a lower-middle-class condominium development. To the character who grew up in those condos and through whose eyes we see the Projects, they present an enigmatic face. On the one hand, they seem full of life. At night people are cooking on balconies “swarming” with small children, and the smells from the cooking and the sounds of music wash over the whole area. On the other hand, “whole floors there were forever unlit, either derelict or the windows blacked out.”

When this character finally enters the arcology, the inside proves no less enigmatic. An entire floor, which we are given to understand is a very large amount of space, is devoted to seemingly randomly growing hydroponic plants and trees forming a Vodou “holy place.” (This branch of Vodou is also a hacker collective, as it turns out, an arguably criminal enterprise, although in the story the hackers turn out to be good guys.) There is also a mosque on the top floor, “a couple or ten thousand holyroller Baptists,” and a “Church o’ Sci…” (probably Scientology). The mechanics of the original structure intended to promote its self-sufficiency are no longer working as designed, and there are signs of decay: the elevators don’t run well. But elements of those mechanical systems have been repurposed to serve the needs of the residents, presumably by the residents themselves. So while this arcology does not work as designed, something about it allows it to be adapted to the needs of its residents in a way the rigorously geometrical Fuller dome does not.

The geometry of living space is also part of Gibson’s presentation in the Sprawl novels of the cigar-shaped space station called Freeside. We can think of it as an arcology that just so happens to be in space, much as Soleri himself imagined. Unlike the evolved order within the Projects, Freeside is meticulously arranged down to the last detail, including the detail that it should not look meticulously arranged. This may be because of the strict requirements of maintaining a livable environment in the hostile conditions of outer space. But Gibson shows this necessity is not all that is going on by giving us other examples of spacecraft and stations that are, like the Projects, much more a product of idiosyncratic bricolage. Freeside’s thoroughgoing planning probably has a good deal to do with its function as a gambling resort, a Disneyland with casinos — and of course both casinos and amusement parks are heavily planned to conceal how they actually operate. It is all the more striking, then, that Gibson wants us to be thinking about cities when we are thinking about Freeside:

Freeside is many things, not all of them evident to the tourists who shuttle up and down the [gravity] well. Freeside is brothel and banking nexus, pleasure dome and free port, border town and spa. Freeside is Las Vegas and the hanging gardens of Babylon, an orbital Geneva and home to a family inbred and most carefully refined, the industrial clan of Tessier and Ashpool.

We see a thread running through nearly all of Gibson’s descriptors: the great Kublai Khan, in Coleridge’s poem, decrees a “pleasure dome” in Xanadu; the hanging gardens are a product of imperial Babylon; the mob builds Las Vegas; Freeside is built by an “industrial clan.” Cities have risen and fallen based on the fungibility of money and power in the past, Gibson seems to be saying, and that will be true of even the most technologically sophisticated cities in the future.

But there is also concealment at work. The motto promoting tourism to Freeside is “Why Wait?” From what we learn, it is clear this means: Why wait to do what you want? In contrast to Xanadu and Babylon, the pursuit of pleasure has been democratized. But appearances are deceptive. Everything is arranged meticulously so that, as in real casinos, you are less doing what you want than constantly being guided to want what owners and operators want you to want. The quasi-democratization of pleasure-seeking conceals a kind of soft despotism of fun and comfort.

However, a goodly portion of Freeside is inaccessible to tourists. Villa Straylight is home to the Tessier-Ashpools, the incestuously genetically engineered remnants of the industrial clan that built the space station in the first place so they could escape the dangers and constraints of Earth. “Lair” is not only metaphorically appropriate for this part of Freeside. Having moved into space, the family found they did not like it very much, and largely closed themselves off from their surroundings in a veritable warren of tunnels. Interestingly, however, Gibson makes a point of telling us that their life support systems are tied into those of Freeside generally; it is crucial to the Tessier-Ashpools that Freeside work as designed and not share the fate of the Projects arcology. Given their money and power, it does work as designed.

Here again Gibson seems to be thinking about cities and self-sufficiency. Like an earthly arcology, Freeside is not literally self-sufficient, even though a visitor would likely experience it as such. Nevertheless, the Tessier-Ashpools’ mode of living (isolation) and reproducing (incestuous cloning) is the reductio ad absurdum of the quest for self-sufficiency. Dependent on the rest of Freeside, they are in fact no more self-sufficient than it is, but they may appear to themselves to be so by their isolated way of life, and in a perverse sense they are more self-sufficient due to their method of reproduction. In another echo of Aristotle, who says that those who by nature cannot live in a city are either beasts or gods, the last vestiges of the family live in a physical setting that, broadly speaking, is reminiscent of an animal warren, even as they have advanced a successful project for the creation of a godlike artificial intelligence. Ultimately, the last representatives of this industrial clan come across as quite inhuman.

Yet they represent an extreme of something we encounter often in Gibson’s novels: the abusive power of corporate money. Nation-state decline due to war and environmental destruction creates a vacuum that corporations easily move in to fill. There are also other ways the vacuum is filled, like the Vodou hacker collective, small potato but nasty gangs in the Sprawl series, the transformed Oakland Bridge in the Bridge series, and the Russian mob (“klept”) in the Jackpot series. Corporate power, however, is the major source of large-scale villainy in Gibson’s novels. While corporations provide order in his mostly decaying or bordering-on-chaos worlds, and while he understands that for most people some such order is necessary and even desirable, the corporations are ruthlessly self-interested.

At this point it is appropriate to make a brief detour into Gibson’s Jackpot books, even if they do not focus on urban America. One setting of the novels is small-town America before the “Jackpot,” a major extinction event for most living things and almost for humans as well. (Strictly speaking, the extinction happens on a different timeline from the American one we are presented with.) In this not very distant future, legal and illegal big businesses dominate the rural world. The other setting is London of a more distant and post-apocalyptic future. London has become a haven for the very well off, and large portions are a historical theme park populated by human-appearing robots. In the wake of the Jackpot, nanotechnology is used to reconstruct the city. Descendants of Russian mobsters pretty much run the city, but competition among the families is regulated by police with extensive surveillance capabilities, a certain amount of algorithmic pre-crime AI, and the power of summary judgment.

As should be obvious from this all too brief summary, Gibson is ringing changes on familiar themes. Due to the self-destructive tendencies of modernity, London has all the artificiality of Freeside and more, and likewise operates to the benefit of close-knit family wealth, with the klept providing much of the order. Although a British government remains, liberal democratic legal and political norms do not seem to have survived the Jackpot disaster and technological change.

However charming some aspects of Gibson’s London may seem, his urban futures thus far seem bleak. Whether there is a long-term future for human beings in the Jackpot series is far from clear. Similarly, the modern world has reached an impasse in the Sprawl stories. The Fuller domes indicate a modernism that is ultimately sterile and self-defeating. They do nothing to contain disordered and decaying sprawl in which freedom all too often spills over into lawlessness. In contrast, in the world of the corporate arcologies, corporations alternate between concealing the rigor of their discipline and enforcing it ruthlessly.

If there is any hope in this world it is in the repurposed Projects arcology (those swarming small children) that can serve what Gibson plainly regards as more humane purposes, transcending both Soleri’s modernist, architect-as-savior grand intentions and its inevitable limitations. It is worth noting that the Projects arcology is characterized by the religions of its inhabitants, a comment in its own right about the limits of modern secularism.

The theme of what the failures of urban modernism teach us about modernity is quite explicit in the Bridge trilogy. When we are introduced to “The Bridge,” the earthquake-damaged Oakland Bay Bridge, in Virtual Light, Gibson (likely giving us the thoughts of his character Yamazaki, a Japanese sociologist of sorts) writes:

The integrity of its span was rigorous as the modern program itself, yet around this had grown another reality, intent upon its own agenda.

What Gibson seems to be getting at by using prominent modernist urban elements in his stories is that some alternative agenda might grow out of or over modernity. As we have seen, in his worlds modernism has sustained damage — although, importantly, that damage is mostly self-inflicted. Yet modernism remains the rigorous core around which a new reality can grow.

However, “rigorous” points in two directions. Modernity values accuracy, coherence, care, and thoroughness; without them, the bridge design and execution would not have survived “the big one” at all. But rigor also connotes death-induced inflexibility. For example, the huge environmental disaster in the Jackpot novels is a consequence of modern rigor in the first sense almost producing rigor in the second.

As far as American cities go, the Bridge trilogy focuses on Los Angeles and San Francisco of a not very distant future in the wake of “the big one.” (The actual Bay Bridge was seriously damaged in the Loma Prieta earthquake of 1989, four years before the first Bridge novel was published. But thanks to modern rigor it was only closed for a month.) Physically, the cities are in many respects the same as they are today. The fate of the San Francisco–Oakland Bridge seems to be paradigmatic. Damaged sufficiently to require closing to vehicular traffic, it has been successfully transformed into a multistoried squatter community, with people building homes and businesses pretty much ad lib, even up into the heights of the bridge’s suspension system. The rigor of modernity here provides an opportunity for something to be built around it, the irritating bit of sand around which the pearl forms.

What is this new agenda, with which Gibson seems sympathetic? It is defined by spontaneously generated order, along the lines of a libertarian community. When the squatters decided to take the Bridge for themselves, there was no plan and no leadership; the whole thing, as it were, crystalized in a moment. Though to outsiders the Bridge’s lawlessness makes it either dangerous or exciting, or both — and indeed there is a thriving underworld — behavioral norms involving exchange, mutual support, and respect for boundaries have also evolved and seem better to characterize the lives of residents. (Here Gibson echoes something of the actual experience of living in Kowloon Walled City.) Power and sewage are handled through some combination of individual ingenuity and voluntary cooperation. We see much more in the way of trust than exploitation among the residents, even though they certainly exploit visitors seeking drugs, excitement, and so forth.

What the Bridge is not is bucolic or idyllic. Its agenda is not the sentimental libertarianism of a simpler or frontier life. There is no return to nature. Just like the damaged physical bridge itself, the residents absolutely depend on the castoffs of modern industrial society, like plastics and even some heavy machinery, to make their society work. The economy is based on reuse and adaptation. Like Kowloon Walled City, the Bridge is only a somewhat self-sufficient city within a city; if San Francisco literally disappeared, the Bridge’s economy and infrastructure requirements would make it fail.

So the Bridge’s agenda is not so much anti-modern as modernity with less rigor. Unlike most modern political arrangements, authority is not centralized; space is not organized by zoning or cadastral systems. Commerce is not controlled by large corporations, and there is a thriving free market: literal unmediated exchanges of goods and services between individual buyers and sellers.

It is not hard to cast a cynical eye on the Bridge’s arrangements. Rather than seeing it as some new agenda, the Bridge’s relationship to modernity, like its relationship to San Francisco, could be described as parasitic, particularly in that the Bridge serves as a home for criminal enterprises. But this is only part of the picture. The Bridge’s residents are poor and dispossessed, the losers in the modern framework. But on the Bridge they are also active and resourceful shapers of their environment and the terms on which they are living their lives. They are, like everyone in the modern world, subject to forces beyond their control, but they are not mere playthings of those forces — which cannot be said of many of the materially successful people in the society Gibson portrays. When hostile external forces literally invade the Bridge, its residents defeat them by their cooperative efforts, paying a large price in the process.

Having said all this, we can still ask: Exactly how is the Bridge’s “agenda” different from that of the modern program? The values the residents embody seem quite typically modern commercial values: hard work, resourcefulness, fair exchange, cooperation, freedom, individuality. In some ways it is on the Bridge that moderns can really be themselves.

The irony seems to be that in Gibson’s worlds these modern values have been pushed to the margins by the ways in which modernity has developed: large corporations, the invasive, intrusive technology that is largely in their hands, extreme social stratification, lawlessness, and environmental destruction.

In the real world, these developments have provoked debate as to whether they are the inevitable expression of modern values, a distortion of them, or signs of an imbalance of some modern traits over others. Gibson seems to have a somewhat different take. The libertarian communities he seems to have most sympathy for are, as already noted, libertarian in a very modern sense. But other forces are also at work.

In Neuromancer, for example, the heroes are anomic and ungrounded, a few of them truly residents of cyberspace more so than of meatspace. But then later in the series we have the intriguing suggestion that the seemingly successful Projects arcology is largely defined by religious communities. Except in the most hyper-Protestant interpretation, such a community is not formed by spontaneous order, but by the acceptance of some degree of external discipline. In the Bridge trilogy there are instances of extreme self-sacrifice that, in one instance, is instrumental in protecting the Bridge from the forces that threaten it. A kind of quasi-familial loyalty plays a major role as well, quasi because in these instances we are talking about chosen rather than birth families.

In the Jackpot books, however, we find something unknown in the other novels: functional, birth-based families, families whose existence as families provides important plot elements. Compared to the families we have seen previously — a mother and son, where the mostly absent mother is killed almost at the start of the story, and the incestuous Tessier-Ashpools — there is a stunning difference. We see a man in London after the Jackpot event whose marriage and fatherhood have, by his own account, turned him into a better human being. We also see the value of intense family loyalty in small-town America in the fight against local and encroaching criminal and commercial forces, albeit with far from complete success. That the London klept should also be held together by bonds of family and loyalty shows that Gibson is well aware these values can be double-edged. Yet this new element of his stories suggests he might be among those who believe the modern program needs to be tempered with values that are not simply modern.

That insight fits with other characteristics of the Bridge community and other not-simply-modern communities we observe. First of all, they are relatively or absolutely small in scale. Second, they have an agenda, a “regime”; they are assemblies of more or less like-minded people. And finally, as already noted, they possess a kind of self-sufficiency, at least in their physical infrastructures; they are not modern cities, intimately and directly tied in with streams of distant commerce. In these limited respects, they remind us of the polis described by Aristotle. The self-destruction of modern cities Gibson portrays makes his cities of the future have at least this much resemblance to cities of the past.

This is, of course, subversive of at least some powerful currents of thinking about “progress,” in which we imagine that precisely what defines it is leaving behind all the things that made the bad old days the bad old days, things ranging from objective conditions such as scarcity to moral vices such as greed. Gibson seems to believe that the only way to leave behind the past would be to leave behind our very humanity — a looming possibility that is certainly present in his fiction, although he tends to draw back from taking it on in any depth.

Gibson’s cities of the future are not urban utopias with gleaming buildings, flying cars, and a comfortable life for all. Neither are they hellscapes of lawlessness, decay, depravation, and oppression, even though they exist in a world where some of our worst fears about war and environmental destruction have been realized. Gibson has plenty of imagination when it comes to the havoc modern science and technology can wreak through assaults on the natural world, weapons of mass destruction, bioengineered weaponizing of the human body, and advanced robotics. The modern program has wrought vast changes, and one would certainly be hard pressed to call them all “progress.” Likewise, Gibson is keenly aware of the way in which virtual realities, omnipresent surveillance, and nanotechnology could change the functions and possibilities of urban living, for example by altering economic roles and extending the reach of public and private authority.

But like cities in the real world, Gibson’s imagined cities are not only the products of their material circumstances — a fact of life that, as he highlights, is often underappreciated by modernist thinker-architects like Buckminster Fuller and Paolo Soleri. The ethical circumstances of the people living in the cities and their various senses of what constitutes a good life matter just as much, if not more. Like real cities, his are products of hopes and fears, and of physical as much as moral inertia and entropy.

Gibson’s cities are complex, morally speaking. As pioneering urban sociologist Robert Ezra Park noted,

a great city tends to spread out and lay bare to the public view in a massive manner all the human characters and traits which are ordinarily obscured and suppressed in smaller communities. The city, in short, shows the good and bad in human nature in excess.

The distinctly modern great city that Park describes here is not, strictly speaking, a city with a regime in the ancient sense, with one ethos or way of life that defines it and is nominally shared by all. Aristotle understood that it took serious effort to maintain a common way of life that developed a common character and moral outlook, and that this effort to battle entropy was built into the basic urban structures, with elements like small size, local gods and shrines, and mythic backstories in support of “laws with teeth in them,” as Leo Strauss put it.

In contrast, the great city that Park describes makes no such effort and is always on the verge of disorder — is in fact disordered from that ancient point of view. Its “regime” is confined to the bare requirements of coexistence, sometimes peaceable, sometimes not, among highly diverse parts. But disorder is essential to its nature. People migrate to these cities in order to take advantage of precisely the freedom created by their disordered circumstances, the complicated knot of dangers and opportunities they provide.

Gibson’s cities of the future follow the logic of “city air makes free,” which started out as a legal principle of the German Middle Ages and opened the door to the modern bourgeois city and in turn the large modern commercial and diverse city. In the process, the legal principle became a kind of existential claim. It now draws millions to growing cities in order to “make their fortunes” by being their truest selves, unfettered by the narrow horizons of small towns and the “idiocy of rural life.”

Or so the story goes. Gibson thinks it is not quite so simple. On the one hand, the freedom to be yourself calls the extent of one’s obligations to others into question, and the resulting collection of individuals (like the hackers) may be characterized by anonymity, anomie, and alienation. On the other hand, as he portrays it, the promise of freedom is likely exaggerated. What is actually on offer proves to be for many the chance to participate in complex relations of interdependence that often extend far beyond the view of a single individual. Whereas Marx and Engels suggested that rural existence is idiotic for making one subject to the blind forces of nature, Gibson suggests that urban existence is unintelligible in the way it subjects people to decisions, however rational, made by people one will never know for reasons one might not have been able to understand.

This, at any rate, is the situation that many of Gibson’s characters find themselves in. Going to the big city means opportunity, and may even offer attractive life-possibilities otherwise unavailable. And yet they enter arenas where the rules have been established to the benefit of those who long preceded them. Gibson’s main characters tend not to stand on the sidelines with respect to this status quo. Sometimes they are engaged in efforts to subvert it, sometimes to support it against those who would subvert it for the worse. In a few instances a character may prosper by learning to be content. Gibson’s cities are as familiar as they are because they are built, as are our cities, on just this kind of struggle, on the fact that great cities are defined by everyone not being on the same page.

As a result of the modern city being the ethical entity it is, changes in technology, in the physical structures of urban life, and in the material conditions of the environment are not going to be the only forces defining cities of the future, as is sometimes imagined by cruder visions of what rebuilding the physical environment can accomplish — witness the wonderful scenes of urbanizing global reconstruction in the movie version of H. G. Wells’s Things to Come. As we see in Gibson’s treatment of arcologies, there are paths by which efforts to create new conditions will be assimilated into existing social norms, hierarchies, power structures, and economic arrangements, contrary to at least the most utopian forms of twentieth-century urban modernism.

Hence, Gibson’s cities of the future are neither simply utopian nor dystopian. Indeed, it may be a result of the two-sided “rigor” of the modern program that we are tempted to imagine the future in terms of this dichotomy. There are forces at work in his cities that tend toward preservation and reform, and forces within them conducive to decay and destruction. Within this framework of contention are possibilities for taking a side on the big issues, for creating smaller communities of the like-minded, and for being left alone, each with its own kind of heroism.

It is all the more interesting, then, how alongside this framework of continuity Gibson does not flinch from presenting the full potential for decay and destruction contained within the modern program. We see in the Jackpot novels the near extinction of humanity, following at least some of the logic of Anthropocene extinction. In a parody of transhumanist aspirations, we also see the creation, through some combination of nanotechnology and bioengineering, of a repulsive, quasi-human species living on an island of scavenged trash. Some characters in the Sprawl novels seem to live out their lives in cyberspace, and the superintelligence created by a genetically engineered elite family could, it seems, have easily controlled or destroyed humanity had it not been distracted by contact with alien superintelligence.

It is an act of resistance to many modern trends of thought that Gibson imagines a human future even to the extent he does. But that human future is not guaranteed; even in the non-utopian form he presents it, it will have to be achieved. Gibson anticipates that cities of the future will, for better and worse, be familiar places so long as human beings, who are in the ancient understanding by nature city dwellers, are still living in them.

Keep reading our Summer 2025 issue

Uncle Sam’s dream house • What toasts your bagel • Tech & marriage • Subscribe

Exhausted by science and tech debates that go nowhere?